Touted as “a new immersive work,” Theaster Gates‘s first museum solo exhibition – self-knowingly titled How to Build a House Museum, and recently on show at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) – lacked the energy that its titular subject, house music, naturally embodies. Whereas house has long attracted ad-hoc communities of revelers who relish in the chaos and excitement of letting go, shaking off the coil and grind of urban life, Gates’s museum communicated itself as a “house mausoleum.” The aliveness of the culture and the music had been subsumed beneath a thick layer of ideology. This wasn’t house music as we experience it in civilian life; this was house music conscripted in the service of social utopia.

The exhibition was divided into several modules intended to interact with one another as extended metaphor. The idea of community ran through it, whether in references to the great Pan-Africanist intellectual W.E.B. Dubois uplifting his people (House of Negro Progress), the unifying influence of the blues (Muddy Waters House), the actual physical act of putting brick to mortar (George Black House), or the all-inclusiveness of the house music scene itself.

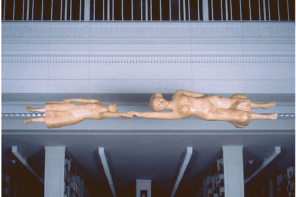

These “houses” were presented as architectural maquettes, paintings, audio, video, and sculpture. Some were self-generated, and some appropriated from the works in the AGO’s collection, such as landscapes by the 19th-century African-American painter Robert S. Duncanson, who was active in Canada, and offers a connection between “Negro Progress” in his native United States and his adoptive Canada; and Baroque sculptures by Massimiliano Soldani Benzi that portray, through Gates’s positioning, Greek Satyrs getting down to Frankie Knuckles’s reel-to-reel recorder. In the words of curator Kitty Scott, “They seem to have crossed time and space to dance ecstatically to the house beat.”

House is Gates’s vehicle – as shelter, as home, as meeting place and musical genre. But these connections (lofty in their aspirations to link real-estate development, social activism, and house music) travel over a trail poorly paved.

The connection between house music and “home” can be inviting; the genre shares its name, after all, with that of our abode, where the family unit can withdraw. The words “home” and “family” are very closely liaised in our minds. However, while “Home” may be a place that is our own, a place to unwind, it’s also a place that costs us. It’s not necessarily a place of tranquility, but rather, for many, “home” means stress, abuse, obligation, unruly children, siblings or a spouse that we don’t get along with.

The house music scene, on the other hand, works more like a Christmas dinner for “strays.” It’s a rag-tag gathering of undesirables, united by a need to escape or find repose.

This is reinforced by the origins of the name “house” within the context of the electronic, sample, technologically-driven genre. House music was originally intended to be disposable, often released in “for DJs only” white-label vinyl and dub plates, consisting of “Disco cutups of famous riffs from the ‘70s” (as DJ Carl Cox put it), and made with cheap “reject” technology such as the drum machines TB-303 and TR-909. Originally, house music was, by definition, ephemeral, and it gained relevance almost despite itself. It was born out of the demise of one of the most reviled musical genres in history, disco, and was never meant to have the solidity of an edifice.

As veteran Chicago producer Paul Johnson and NY producer Frankie Bones put it in Lara Lee’s Modulations:

Disco died in ’79 and there was a void in the music, which, Frankie Knuckles was in New York, he went to Chicago and caught the very beginning of it … He opened up a club which he called The Warehouse, so, after a while, people get used to saying things so they just chopped it from Warehouse to “House” … People would go out after hearing Frankie play at the Warehouse and be like, “we want soma those house records,” meaning “Warehouse” records. The club Warehouse … Really what it was, [it] was just disco. Disco, with some upbeat R&B songs and they just named it ‘house’, because it was played at the “House.”

House music is not about the tranquility and serenity of home (unless home happens to be a large room with a pair of technics turntables, a mixer, and a killer sound system animating sweaty, drunken bodies). It’s not the music of awareness. It’s a type of music that‘s meant to make you forget. Chicago house producer Derrick Carter says it best:

Life is hard. You gotta go bust your ass for about eight hours a day, you know, making shit money, barely able to pay your bills; like, you need a good six hours where you don’t have to worry about shit … you need to be able to have a chunka time that you go somewhere and like, no matter what, you know, (whether) it’s raining outside, I got two dollars, my girlfriend left me on the way here, I locked my keys in the car … you know, all kindsa shit.

Unlike Latin music (which was a major influence in the development of the genre – see Latin house and Tribal), house music is “four on the floor.” The beats are steady and move at a comfortable tempo (usually at between 120 and 130 beats per minute); there are no complicated syncopations to worry about, no elaborate dance steps to master, anyone can get down to house music. And this is why it’s so welcoming. To enjoy house, you only need to get down and forget your troubles. And as humble an aspiration as this seems, being able to forget the daily grind is one of the scarcest commodities going.

At its base, house is a hedonistic art form. So, in Gates’s How to Build a House Museum, the gravitas of social engagement doesn’t jive with the animating spirit of its subject.

A forced arrangement between house music and social activism felt particularly present in a suite of paintings based on statistical data pertaining to the progress of African Americans (as collected by Dubois); in Reel House (featuring a shrine to Frankie Knuckles’s music, as well as the late DJ’s collection of baseball caps); and in the locus of the exhibition, Progress Palace (an immersive video installation featuring a large multifaceted mirrored sculpture that rotates like a Tatlin-tower disco ball).

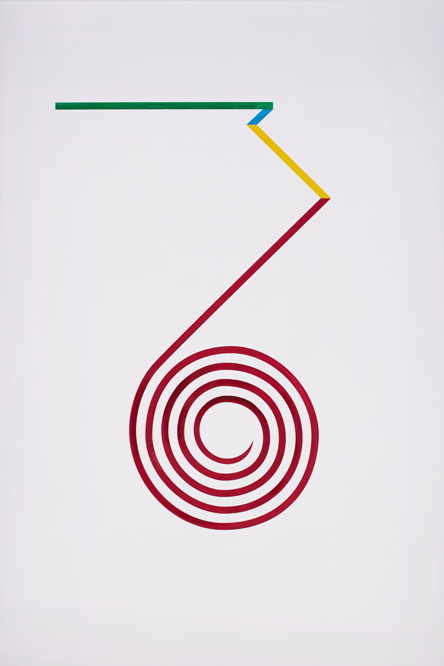

Gates and Scott refer to the spare paintings as comprised “of quasi-scientific forms [that] abstract the language of color bars, pie charts, and other means of representing quantifiable data.” They are compared to the Suprematist abstractions of Kazimir Malevich, and mark “a significant departure” for Gates. As geometric abstractions, they border on color field, though these are thin approximations. One features a red spiral from which a jagged green and yellow line juts out; others are hung with square forms and horizontal bars, and made occasionally erratic by squiggly lines. These shapes are meant to convey data that’s been compiled on the subject of African Americans (their literacy, their geographical centers, etc.), then removed from its source material, and emancipated into primary-colored gestures of abstract flight. But unlike Malevich’s Suprematist paintings, with graphic weight and trembling presence, Gates’s abstractions are never more than diagrammatic. Thinned-out and paired off from their content, they don’t, as art, take on any height.

What weakens these further is the fact that an inner gallery in fact does retain all their data – in sepia-tinged, historically-performed charts (made after the originals) that relay everything the abstractions stand for – and depart from. Why did Gates feel the need to, at once, double-down and undo his first gesture? The didactic urge was apparently too great.

Ringed by these enfeebled abstracts, Shrine weakly pulses with a beat. The Hi-fi equipment encased within its tabernacle – made up of wood rescued from Chicago’s demolished houses of worship – feels suffocated, suffering a constraint on the lively house tracks emanating from within. This shrine would work for an artist like John Coltrane, given his transcendentalist compositions and spiritual aspirations. But when applied to house music, the demolished-church materials affect a confused metaphor. Because although “garage house” weaves gospel melody lines, house music doesn’t lend itself to worship, unless it’s a remix of The Winans (the first family of contemporary Gospel music), or the songs of Chicago house giant Roy Davis Jr. (his track Michael, about the Christian archangel Michael, comes to mind). Moreover, house music enlists the help of Gospel’s soaring melodies and references to the love of God allegorically to enhance the euphoria on the dance floor, much in the same that the Persian poet Molavi (Rumi) used the intensity of romantic love as an allegory for the love of God in the faithful, or Ray Charles combined Gospel with R&B. This is to say that house music is a secular genre that borrows from the sacred tradition, but is not a “spiritual” art form (rather, it concerns itself with the ins and outs of romantic love). Nailing it to its metaphor has the deadening effect of making the transcendental literal.

Elsewhere, Knuckles’s reel-to-reel is displayed is a fetishized object, somehow devaluing its aura. The gesture seems as flat-footed as if one were to erect a shrine to Jimi Hendrix’s guitar. It’s not the instrument, but the artistic prowess and intellect of the person wielding the instrument that carries our wonder.

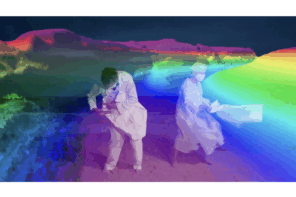

In what is staged as the exhibition’s climax, Progress Palace, Gates has created a pseudo-club, anchored by the spinning-mirror sculpture, a ghost DJ booth, and framed by a video projection entitled House Heads Liberation Training. The title of the video feels ominous, like some sort of “re-education” program, and sure enough, features a slow-moving group engaged in the beginning stages of learning a choreographed dance. In this, the title reveals itself to be a contradiction in terms. House heads are individualists. A “head” is a person who is in the know; someone who is not a spectator but a participant, but most importantly, a tastemaker and independent. The failure or success of any house party is dependent on the attendance of the house heads, who move to their own beat. The idea that a house head could be “trained” is reminiscent of the statement by the Slovenian group Laibach, that “Disco rhythm stimulates automatist mechanisms and co-forms the industrialization of consciousness according to the model of totalitarianism and industrial production.” The stance of predetermined movement, evidenced in the “training” video, works against the “anything goes” beckoning of house music, as well as its emphasis on temporary ad-hoc “communities” that form out of diverse individuals, which brings us to a telling feature of Gates’s version of house music: its lack of diversity.

Frankie Knuckles came up with Larry Levan, the developer of the musical language of house, during the 1970s. They played at New York’s Paradise Garage and Continental Baths, one of the most famous gay clubs in the world. Knuckles met Levan while they were both in the Harlem Ball Culture scene (featured in the classic film Paris is Burning), where they excelled as dressmakers. The house scene was predominantly formed out of the LGBT community: Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles were gay, as were Arthur Russell (another gem in the house firmament) and David Mancuso, the inventor of the “private party” format, and founder of The Loft; but it attracted numerous types of people of diverse backgrounds and persuasions. Early house pioneers were multicultural and pansexual. However Gates’s exhibition doesn’t touch on this. Standing in the middle of his empty dance floor, I found myself wondering, if it’s a museum to house music, where is everybody?

And if Frankie’s brand of house, as the show’s didactic text proclaims, established “safe spaces for creative people on society’s margins, whether in New York, Detroit, Toronto, or London,” then the exhibition could have benefitted from a collaboration with the Toronto House music scene, which has been home to legendary clubs like Nuts and Bolts, The Boom Boom Room, the Limelight, and innumerable illegal booze cans; and produced leading DJs like Denise Benson, Douglas Carter, Dino and Terry, Quadrasonic, Andy Roberts; Chicago-born, Toronto-based DJ Sneak (of “Fix My Sink” fame), Dirty Dale, and the Play Records crew, among others. There were missed opportunities, here, where the exhibition could have engaged in real community-building by setting up afterhours parties in rented spaces (like warehouses!), and bringing members of the artworld and “house heads” together. With less of an aspirational tone, and more “four on the floor,” it’s an exhibition that could have realized its ambitions.

House music does generate temporary “communities,” and in this way How to Build a House Museum’s attempt at connecting the dance-club scene with political awareness can feel sincere, hopeful, and endearing. But on close examination, the connection appears cosmetic. By conveying only one perspective, presented through the deployment of parallels between thinly laid-out premises (house music vis-à-vis historical house museums; house music in relation to political ideologies centered around ideas of community engagement-cum-real-estate-development), the exhibition has the feel of a beautiful edifice built on a foundation made of something sinking.

Museums, with their associations to the ethnographic, to that which is past, that which is studied and dissected by scholars, don’t lend themselves to the music, which negates the cerebral. And ultimately, Frankie Knuckles and Chicago house don’t need a museum. As any DJ will tell you, just put some wax on the platter, drop the needle, crank the bass bin, “Move Your Body,” be blown away. This is it: you are alive.

exactly my feelings, U. house music crossed cultures almost immediately and succeeded because it appealed to a diverse group globally (and if it was meant to be ‘owned’ by a subculture, it would never have been put on wax and distributed worldwide. by the mid eighties you could hear it from calgary to tokyo.) the exhibition entirely missed the groove, the pedagogy burying the pulse. “who needs to think when your feet just go” is tough to capture in an institution, i suppose, which is by definition — especially these days — in the biz of being didactic and messagey. the hats of djs felt like memorabilia (hard rock cafe); the infographic paintings felt like either space filler (gotta cover those walls) or a need for something sellable (but important, and ‘about identity’) post show. that Shrine felt like Madam Tussaud’s; the disco crystal, with the lifeless dj stand, and the (i thought very unsoulful) instructional video, and especially the soundtrack, which so totally missed the emotional build/release of the music… all made it feel like an empty house. the best works, the most moving works were the brick pieces, which felt real, and personal, not pedagogical… they felt like lyrics, not instructions.