In the year 2000, curator Phillippe Vergne staged an exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis titled Let’s Entertain: Life’s Guilty Pleasures. It was a huge show, featuring over eighty artists, and presented its theme – the intersection of contemporary art and the “leisure industry” of spectacle, celebrity, consumerism, and pop culture – as a generational survey, encapsulating art’s multi-disciplinary, media-savvy spiritat the end of the 1990s. The roster included many of the moment’s biggest names, from Neo-Pop and YBA-affiliated artists like Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, Maurizio Cattelan, and Damien Hirst, to relational aesthetics figureheads Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe. The focus was on work with media formats or imagery from fashion, advertising, broadcast TV, retail architecture, and music videos – Doug Aitken, Douglas Gordon, Gillian Wearing, Martin Kippenberger, and Bernadette Corporation, for example – with General Idea, Dara Birnbaum, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, and (of course) Andy Warhol presented as notable progenitors.

Let’s Entertain also involved one of the earlier attempts by a major museum to incorporate internet art into its programming. The Art Entertainment Network (still online!) was a “web portal” and online exhibition that accompanied the physical museum show, intended to address the addition of the internet to a mediascape already crowded with “television, movies, video, newspapers, magazines, cartoons, billboards, posters, and commercial packaging.” While the millennial flirtation between new media, net art, and museums was awkward and fairly brief (the Walker Center’s new media outlet, Gallery 9, was founded in 1997 and folded in 2003), Let’s Entertain helps us reflect on how, fifteen years later, the internet now colonizes pop culture wholesale, absorbing, transforming – and in some cases, eliminating – older media formats. Now that the phones people carry in their pockets have dramatically more processing power than the highest-end desktop computers of the early 2000s, the spectacle, celebrity, and consumerism that Let’s Entertain pondered are all mediated in one way or another by digital networks.

Which brings us to You Won’t Believe (…), an exhibition at Montreal’s Division Gallery that revisits the theme of Let’s Entertain from our present-moment perspective. Curated by gallery assistant Loreta Lamargese, a recent University of Chicago art-history graduate who was only hired last November, the show is a brash, ambitious departure for the gallery, featuring a large cast of local and international artists. The full title, You Won’t Believe What Happened When These 22 Artists Got Together for a Show, nods to the typical headline format of Buzzfeed and other click-bait sites, whose model of attention-grabbing listicles, viral videos, and aggregated news has become generalized now that the internet is the primary vector for all other media. Entertainment bleeds into everything as culture flattens into what we euphemistically call “content,” a malleable substance that’s algorithmically optimized to appeal to specific users even as it races to exploit the broadest and most atavistic human impulses: visual pleasure, empathy, and outrage.

Contemporary art is not exempt from these dynamics. The social and participatory turns that art has taken since the 1990s already prepared museums and galleries for more ephemeral, experience-based, and spectacular kinds of programming. Lately, this kind of theme-park art tourism – exemplified by the Museum of Modern Art’s staging of Marina Abramovic’s retrospective, Random International’s Rain Room, and the recent Bjork fiasco – has been geared towards progressively more grandiose (or desperate) forms of attention-mongering. On a more subtle and pervasive level, the widespread availability of high-quality installation photos (whether via galleries’ own websites or aggregator blogs like Contemporary Art Daily) has vastly increased the tempo of art distribution, with considerable effects on the formation of consensus, the exchange of influence, the process of legitimation, and (not least) the calculation of market value.

The artists in You Won’t Believe are mainly celebrating art’s immersion in social circulation, and the curatorial premise takes the internet’s attention wormhole as a sublime, even triumphant manifestation of the human thirst for knowledge and novelty. The brief curatorial text hails “the surprising pleasure we take in both the act of searching and what we find.” The work itself falls into two categories, often overlapping: eye-catching, post-Pop art that aims to entice viewers through friendly, seductive visuals, crass sensationalism, or both; and cooler, more detached art, loosely associated with post-internet aesthetics, that examines the mechanics of digital mediation itself.

Entering the space, you encounter Jillian Mayer’s large-scale photograph, My Phone Died. Meet me here. (2015), which depicts the titular phrase spray-painted in giant letters on a detached outdoor wall, presumably in her native Miami. While the print (edition of 5) is nominally the piece, the image also circulates via Mayer’s own Instagram account and through the numerous people that encounter the actual message and post it to social media. It’s a virally optimized take on the conceptual one-liner that plays on our helpless dependence on digital connectivity.

Meanwhile, on the opposite wall of Division’s entryway, four large prints by Carly Mark juxtapose famous artists with packages of chips (Doritos Rivera; Utz Fischer; Francisco de Goya Plaintain Chips, all 2015), a joke so pointless and unfunny it probably wouldn’t even make it onto The Jogging (if it were still active). As a whole, the exhibition oscillates between these two poles of incisive self-reflexivity and simple puerility. But whether they aim to be seen on more populist, “creative” blogs like It’s Nice That and BOOOOOOOM! or on more highbrow venues like DiS and Contemporary Art Daily, most of the artists in the exhibition are bypassing established protocols for institutional validation and aiming instead for simple visibility – the point is to be actively circulating and connecting in the social network of art.

A number of the artists in the show, like Jaysson Musson and Brad Phillips, have prominent web personas: Musson as irreverent Youtube art commentator Hennessy Youngman (though he hasn’t posted a new video since 2012) and Brad Phillips as a voyeuristic Instagram bad-boy and contrarian art critic. Other artists, including Carly Mark and Chloe Wise (whose solo exhibition opens at Division March 26th) are fresh out of BFA degrees and have enjoyed more exposure in fashion magazines and style blogs than in the art press. As post-internet has become a market-friendly hashtag, artists associated with the term have also been increasingly supported at very early phases of their careers by upstart commercial galleries and speculative collectors. The latter, in particular, have already fuelled skyrocketing price jumps (and equally precipitate falls) as they chase the rapid turnover and cross-pollination of stylistic gestures that’s been made possible by extensive documentation of exhibitions (and even works in process) across the board.

Post-internet tendencies are most visible in the first main room of You Won’t Believe, which focuses on, as curator Loreta Lamargese puts it, how information is rendered aesthetic “and consequently digestible.” Matt Goerzen’s Virtual Solidarity Sale (2015) imagines a sale of combat gear for army personnel at Best Buy and pairs laptops photo-printed on stretched canvas with unframed inkjet printouts of photos and comments from the Facebook pages of soldiers. Year Round Relief (2015), by New York-based duo BFFA3AE, also involves inkjet prints pinned to the wall – eight of them, featuring a moodboard of images for a prospective film, hang above a shelf bearing two humidifiers where the printed sheets slowly curl and crinkle. Unfortunately, this humble installation captures little of the virtuosic depiction of teenage vulnerability and screen-mediated intimacy in BFFA3AE’s short film Live [EXPLICIT] (2014), which Lamargese recently screened at CK2 Gallery.

Three C-prints from Wyatt Niehaus’s Lights Out series (2014) hang on the opposite wall. The images are dimmed, red-hued renderings of luxury-car interiors taken from the factory floor; the absence of humans suggests the automation not only of manufacturing but of design, trend forecasting, and the production of desire itself. Niehaus imagines a post-industrial world of commodities circulating without the need for either producers or consumers.

Aesthetics drawn from production design and branding are also apparent in the digital abstractions of Travess Smalley, Erica Ceruzzi, and Mike Goldby. Smalley has already drawn considerable attention for brightly-hued formalist works that involve feedback between Photoshop processing and hands-on materials like collaged paper or clay. Here, one of his most recent works, Vector Weave – Action 6 over 7 – CG_ColorPhotocopy_Print 30 (2014), is a nearly black-and-white UV print on vinyl of layered vector graphics that resemble stacked or corrugated metal. It’s more transparently harsh and digital than his work to date, closer to the process-based abstraction of Wade Guyton, and seems calculated to impress and intimidate. By contrast, Ceruzzi’s splashy, graphic works mangle the logos of sportswear companies into unrecognizable squiggles and apply them as vinyl cut-outs to canvas that’s been dyed in watery, swimming-pool gradients. Goldby’s Layer Study (Nike Flyknit, Knights of Sidonia, Terre d’Hermès) (2015) also references athletic wear, combining a cologne ad and manga illustration with the mesh pattern of Nike Flyknit sneakers. As references to the current vogue for “athleisure,” both Ceruzzi and Goldby’s abstractions condense and rarefy lifestyle trends into something recognizable as art, while perhaps also nodding to the “Athletic Aesthetics” ethos.

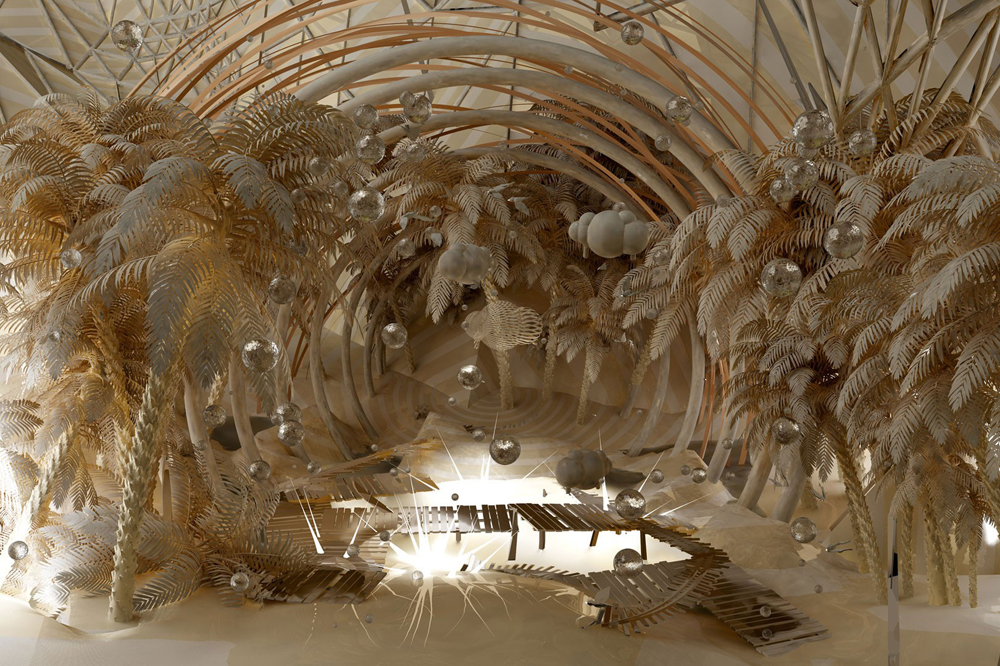

Leisure is more explicitly the theme of the exhibition’s second room, which is full of references to tourism and the beach – a blast of artificial sunshine in the midst of a Montreal winter. The room is dominated by Eric Yahnker’s monumental (and monumentally silly) Bey-watch (2014), a technically accomplished, life-size pencil crayon rendering of Beyoncé riding a surfboard into a sunset, wearing full gold lamé. Les Ramsay and Paul Butler are odd men out, in that their bodies of work have little to do with the exhibition’s overarching premise, but both contribute tropical-themed pieces here. From Butler, collages of beach scenes with slogans affixed (“DO IT”, “Let Yourself Go!”, etc.) ;from Ramsay, paintings that incorporate patchwork beach towels adorned with palm trees. There’s another Jillian Mayer piece, too – a video titled Hot Beach Babe Aims to Please (2014) in which the artist goes for a dip in the ocean trailed by a swarm of cursor arrows that prod at her body. She’s literal clickbait.

More literal by far, though, is Chloe Wise’s Frisky Hungry Blonde (2015), a plasticized, disembodied female torso with a wet, white T-shirt plastered over its silicone breasts. If this section of the exhibition is Spring Break, Wise is its Girl Gone Wild – a party-hard, do-it-for-the-lulz image that she likely refined during her tenure as a studio assistant for noted “Net Art Bro” Brad Troemel.

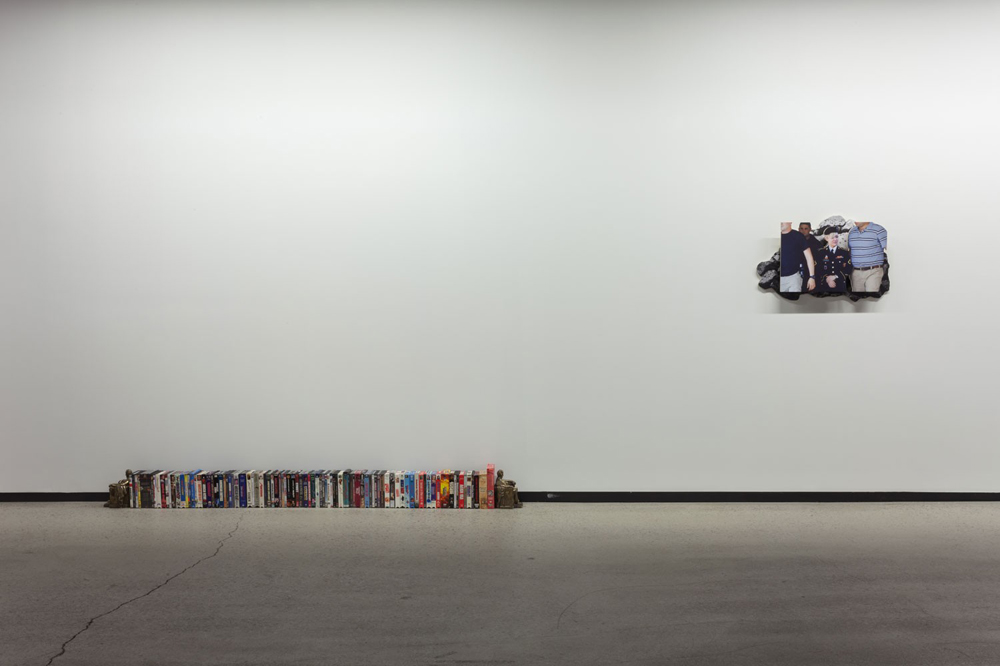

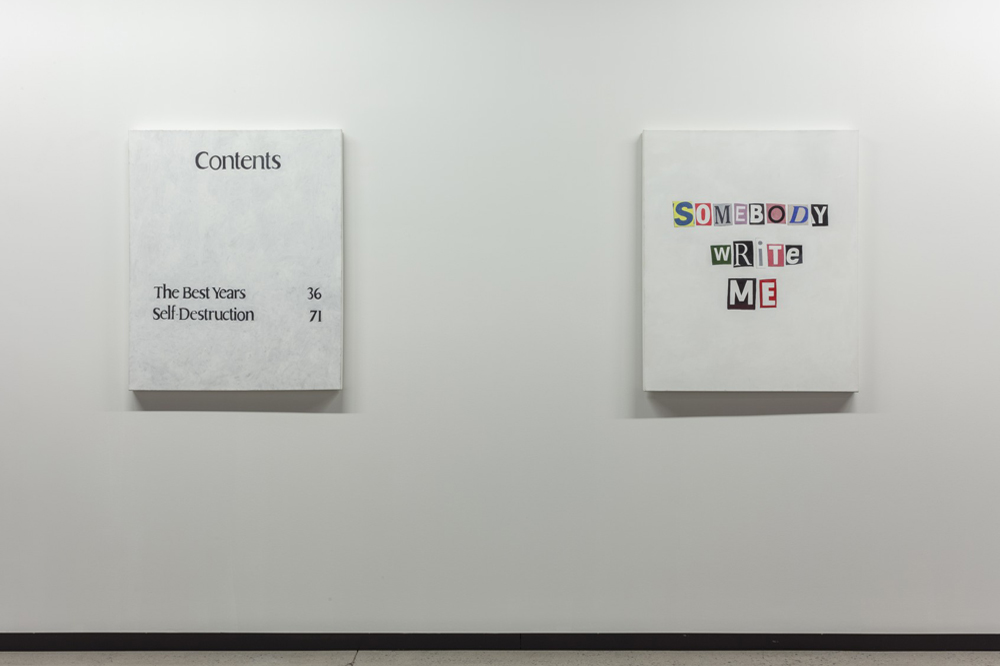

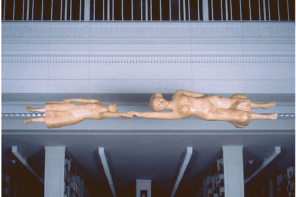

The third and final room feels a bit like a catch-all space for the remaining art (it’s where you can find paintings by Phillips and Musson, for instance), but a number of the works loosely cohere around the theme of film and television. There are two more Eric Yahnker pieces, both readymade sculptures rather than paintings. One is a collection of 92 VHS tapes that all have the word “American” in the title, bookended by brass Abe Lincoln statuettes. The other is a single VHS tape of the 1989 film Glory on a plinth, with a hole drilled through the center. The title? You guessed it: Glory Hole (2013). Slightly less boneheaded is Nick Demarco’s Miley Cyrus As Chelsea Manning (2015), a digital print on plywood from his series of fictional films constructed through sculptures and audio. A painting by Thea Govorchin titled The Power of Love (2014) combines an abstract form from Matisse’s cut-outs with a hentai nude, a pendant to a similar work near the gallery entryway with the truly offensive title Subservient Asian Afternoon Sandwich (2014), both of which call to mind this image by Instagram art satirist freeze_de.

In an adjoining chamber off the third room, several cyberpunk-ish abstract paintings and flooring repurposed from old movie theater carpet (all by Brendan Flanagan) provide a mise-en-scène for an early video work by Jon Rafman (DU3L, 2009) in which a showdown from a samurai film is overlaid with primitive, TRON-esque CGI effects. Like Yahnker’s VHS tapes, Rafman’s video and its setting invoke nostalgia for pre-internet entertainment and the environments in which it was consumed – suburban basements and cineplexes, for instance. I have to admit that it stirred a surprisingly profound wistfulness in me for the hours I killed playing Bushido Blade, but it’s also another example of an adolescent sensibility in a show that already has much more of it than I’d like.

One of the more striking differences between You Won’t Believe and Let’s Entertain is the degree to which the work in the latter moved between different media formats and audiences, using the museum as a space for deconstructing and critically analyzing pop-cultural forms – the catalogue for that exhibition billed itself as a cultural studies reader, reflecting art’s proximity to theory and the academy at the time. If the art in You Won’t Believe lacks that kind of intellectual heft, it’s partly because the speed of art distribution (and commerce) has outpaced the need for critical legitimation. Critical discourse struggles to catch up with swiftly-mutating art trends that seem designed to resist analysis in favor of immediate, affective impact. The gallery itself has also lost much of its traction as a separate space of cultural activity as it’s been flattened by the internet’s steamroller of cultural transmission – more media is available at once than ever before, but paradoxically, it’s all available via the same channel. Since artworks will be primarily viewed online regardless, they’re forced to compete on the same playing-field as Buzzfeed, and so they adapt accordingly. As Jesse Darling said, “every artist working today is a post-internet artist.” Which is why, even when it’s repellent, the sensibility displayed throughout You Won’t Believe is irrefutably relevant.

Like it or not, you’ll be seeing more of this.