On a perfect spring day in late May, I found myself huddled in a crowded gallery for an artist talk, my head leaning forward, a plastic cup of water by my feet. I was entirely content to be where I was, feeling nearly giddy as I ignored the evening light. Good artist talks are rare, but the ascendant star Anique Jordan had the room in her grip. For Jordan’s first solo show – and her first commercial gallery outing, at Zalucky Contemporary – she held two sold-out talks wherein she paired herself with, respectively, activist Tina Garnett, and journalist Priya Ramanujam. There for the latter event, I noticed I was one of only a handful of white people – a rare reversal of the norm in Toronto’s artworld, even within the context of the city’s prominent multiculturalism. A steady trickle-in confirmed that many of the audience members had made the long trek from Scarborough, a division of the city that both Jordan and Ramanuiam call home, and a central subject of Jordan’s exhibition, Ban’ yuh belly. Each time the door swung open, the artist would gleefully break from her conversation to call out the tardy arrival – “Stella, Jordan! Y’all late!” – before pivoting back to the subject of the enduring, steady grief that she and her community must contend with in a place where the loss of its members is so frequent. Grieving one loss floods into grieving the next.

Priya Ramanujam and Anique Jordan, artist talk, May 23, 2019, at Zalucky Contemporary. Photo: Sky Goodden.

Using a Trinidadian expression for her title, Jordan reflects on what her mother asked her when she expressed her constant mourning. “What are you doing to ‘Ban’ yuh belly’?” she asked. The expression was originally used for women who gird their backs as they carry a child to term – wrapping up, preparing, taking care. It’s now used more colloquially as “take care, bolster yourself for what’s to come.” Across her exhibition and her talks, Jordan flicks her attention to Toronto’s disregard for black death, and pairs it against the attention afforded white victims instead, most memorably the random civilian death of Jane Creba, in 2005. She also turns her gaze to the question of “where art gets to live,” after having been first approached by Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival – of which this exhibition is a part – with an invitation to pitch a project two years ago. At the time Jordan had suggested doing a billboard in Scarborough. “And they said, ‘but who will see it?’” she recalls, scanning the room in disbelief.

For an exhibition that runs deep with such injuries and rumination, and which insists on bringing the expression of loss to the front, I felt Jordan’s exhibition wanted another conversation. So we approached the laureled artist, Michèle Pearson Clarke, who works in similar media (she was recently appointed Photo Laureate for the City of Toronto), and with resonant themes of dispossession, grief, community, and affect. Clarke sat down to talk with Jordan about the spaces they inhabit together, and those from which they depart.

– Sky Goodden

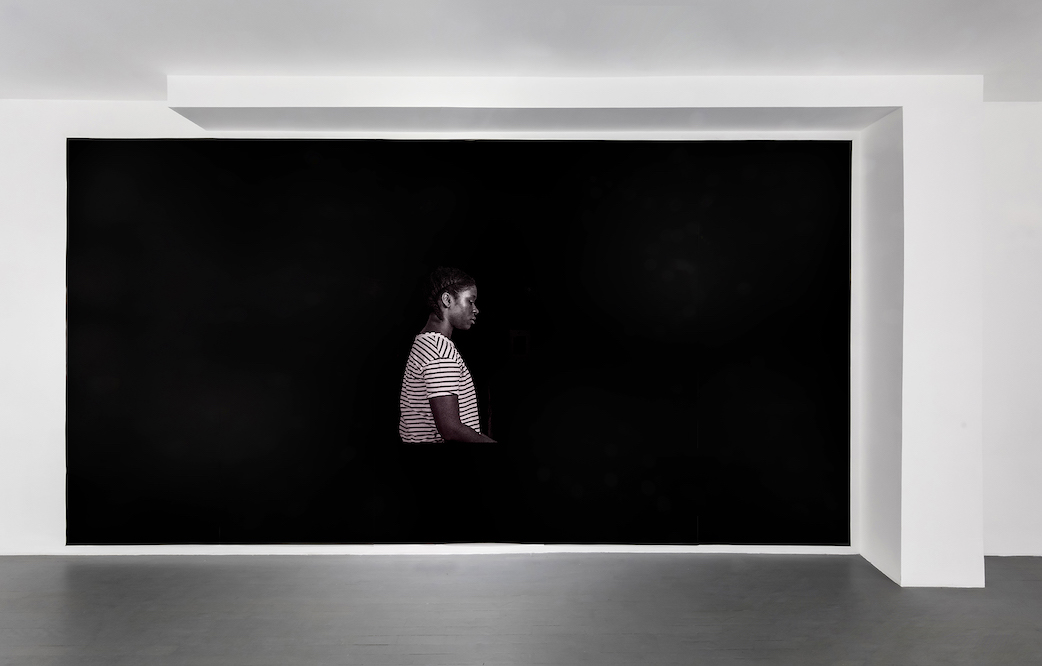

Anique Jordan, “Solo,” 2019. Courtesy the artist and Zalucky Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Michèle Pearson Clarke: I know we talked a few months ago while you were working on this project. But after we talked, how did you arrive at the choices that ended up in this exhibition?

Anique Jordan: I think the ideas that I initially approached you with were always there. One of the things that helped me feel at ease in working on the scope of things, though, was when you said “think about a starting point.” Which helped me to not be thinking of these broad, sweeping terms like “loss” or “violence” in a way that removed myself. Instead I gave myself permission to enter it in a way that I’d been afraid to before. By doing that it reaffirmed for me that these are the things I’m dealing with and that I need to be doing this kind of work. I knew I was affirming the grieving that I had been feeling and giving a place to that loss. It was like saying “I can live with you in a way that I can work with you. It doesn’t have to become debilitating but it can do something different for me.”

MPC: Yeah, I think about that a lot in my work, too. I think about “what is productive” in the grieving experience. Both for me, in terms of my own personal experiences and deepening my self-awareness and healing early trauma – but also “what is productive” in terms of making a work that can say something to people, and make people feel less alone, and hold space for other people’s grief. I think if there’s a thing I’m trying to do in all the work I do, it’s to hold space for other people’s grief. I’m wondering if that’s what you see yourself doing with this exhibition?

AJ: Yeah, I never thought about it as holding a space for grief, though that could be a way to interpret it. How I entered into my thinking was, “how do we affirm the anxieties, depression, the things we experience in our bodies – they’re not ill-placed. There’s a reason you’re experiencing these things.” I will say it all came about for me through a conversation I was having with a friend, who I was talking to about the amount of people I’ve lost, the level of grief I was carrying, and she said, “you know, that’s not normal.” And I thought, how many of us are carrying this level of grief and don’t have it acknowledged, don’t have someone to say “this is why you’re experiencing these things.” Hearing “that’s not normal” was freeing in a way, because it meant that everything made sense – my body reacting this way …

MPC: So she meant it’s not normal to have that much loss?

AJ: Yes, to be dealing with that much violence.

MPC: I see. Because I thought you meant she was saying it’s not normal to be feeling what you’re feeling. Which is a cultural message around grief: “get on with it.” That if you’re actively grieving all the time, that this is not normal. This false idea that still lingers in the culture that grief is a stage-like process – that you move through it and then you continue on. And it’s not actually how we grieve at all. In fact, all humans are walking around doing their best to cope with grief, whether due to violence, or different reasons that have produced it. But loss to me is a basic human condition. Life is just one loss after the other.

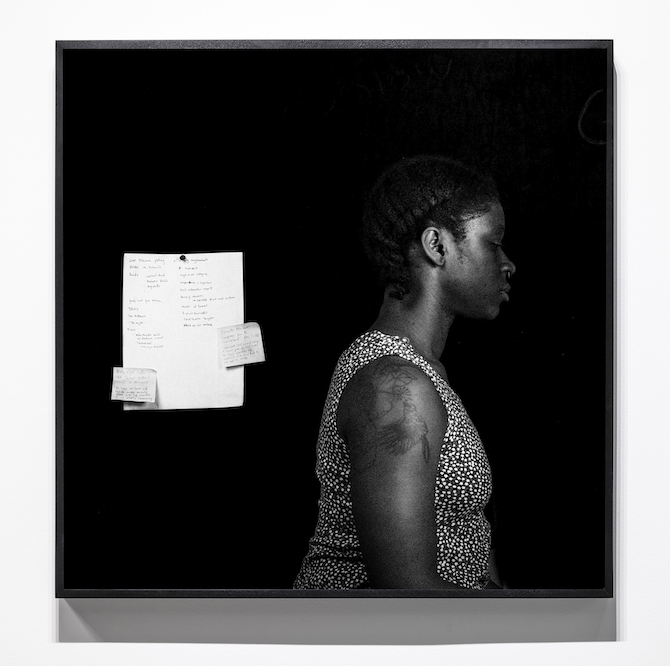

Anique Jordan, “Notes,” 2019. Courtesy the artist and Zalucky Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

AJ: Yeah. My work is about grief – particularly around violence, because I was thinking of the friends I’ve lost to murder and suicide – but what I was cautious about and what sort of weighed on my heart was whether or not, when I produce work that comes out of a place of grief, I am producing something that is harmful to others? That was a big concern. Has that question ever come up in your work?

MPC: That hasn’t been my experience at all. What I have found is that there’s so little room and space for grief: in our culture it’s a private thing. So as an artist, I’m bringing grief into a public space. Even “How are you doing?” / “I’m fine!” That’s the default in our culture. If you’re having a rough day or you’re sad, you don’t go to your friend’s dinner party. You stay home, and you cry. Because people are not comfortable if you’re sitting at the dinner table and you start to cry. I think we should all be able to go, “Oh, Anique’s crying for five minutes. That’s cool. Pass the wine!” [laughs] There should be a space to do that, to not exclude her because she’s grieving. So for me I don’t worry so much about causing harm to people. For instance with Parade of Champions, and particularly the way that work was installed in a small room, a lot of people talked about waiting to go into that room alone, and watch that piece and sit with it. So many people sent me emails to say for example “while I was in there, I started to cry, to grieve my grandparents who I had never fully grieved. Because they were old, and everybody said they had a good life and it shouldn’t be a sad thing. But it was a sad thing. And that didn’t come out until I was in your exhibition.”

Michèle Pearson Clarke, “Parade of Champions,” 2015. Installation view at the Ryerson Image Centre. Photo: Eugen Sakhnenko.

What I do think about is the long history of black people’s pain being a public spectacle for public consumption. We know that a lot of the audiences looking at our work are white – that whiteness is over-represented in the gallery space. So how do I make work that is a representation of pain and not exploitative, and not a spectacle, and not offering up that pain for consumption?

AJ: That’s a real question for me and I feel that. In producing the work I’m asking, “is the risk of a white person experiencing this work worth what it does for a black person’s body?” Can I weigh that out and know that there’s something encoded in this, that’s so personal for another black person viewing this, that it surpasses an ability for a white person to even interpret it? I saw this so many times within the show, particularly with a lot of my aunts coming by, or a lot of younger women, who would notice instantly the style of my hair. And they’d ask, “why did you decide to twist it?” You know? [laughs]

MPC: Yep.

AJ: And I just thought to myself how private that is. Very few people will know to question that, or to interpret just a simple thing like how my hair is slightly visible in some of the images and how you can see it coiling down around my ear. I feel that those subtle gestures allow us to have a secret in the image that can’t be accessed by other folks.

But I did question whether I was working with a pain that allowed other people to enter it and speak through it. And because there was so much conversation around Dana Schutz a couple years ago, which pushed the conversation further about how artists use black pain as commodity – it became something that I had to check myself about. But I realized, “no that’s not the type of work that you’re doing. The sentiments that we’re working from will never produce work like that.”

MPC: Well I don’t know, I disagree with the idea that any insider is incapable of reproducing oppression. This idea that a woman will always make only authentic feminist work, or that a queer person will only … you know? We are all raised in this culture. I’ve seen black people make work that’s exploitative.

AJ: But that’s not what I mean. I think it’s possible to produce black pain; I just mean that it wasn’t possible given the sentiment I was entering the work through. And it wasn’t a concern that I wanted to have at the forefront of my mind, because it could have dictated a lot of the choices I was making.

MPC: Yeah it does shape your choices. But I think, as my practice develops, you come up with these ideas and you have your intent, but you don’t know how it’s going to operate until it’s in the space. So every time I have an exhibition and I’m able to engage with audiences, to see how the work lands, to see what it produces in people, it’s an ongoing learning in terms of making choices. My work always involves a high degree of asking people to be vulnerable. And I’ve had a number of projects in the past few years where the participation has been way less than anticipated. So I’ve come to understand that I am not a good judge of what other people will be willing to do. Because I am extremely comfortable with vulnerability. So seeing that [lack of participation] happen over and over, what do I shift? What formal choices do I make to allow people to be vulnerable, but introduce a level of opacity, a level of refusal that allows or invites more coverage that other people might require.

AJ: For me, I learned a lot in working for a commercial space. This is my first time ever showing with one, and there are so many questions I never even thought to consider. Working around grief in a commercial gallery, I have to contend with and make sense of that. The other big piece that comes out of that conversation about “what do you produce once the work is out of your hands” is also so much about the location of the work. The work is about Scarborough, where I grew up, the community I lived in my whole life, but the show is in this downtown space – not even just downtown but all the way west. It’s so inaccessible for so many people whose lives were developmental for this work. It got me thinking, what happens in the city where so much of the artworld is segregated in these ways. And the work is really dealing with that. Growing up in Scarborough, you get relegated to being part of a population of disposable bodies. The city sees Scarborough as a dead space, it’s been left for dead. The LRT will die soon, for instance. So if I had this experience again, I would bring more foresight to thinking about the location of where the work is placed, and where it could be accessible for the people I’m talking with. I would have done it in a different way, probably a less precious way. I would have done it in a way that people could have interacted with it, made it more tactile, something they could own, could touch. Not framed inside a gallery.

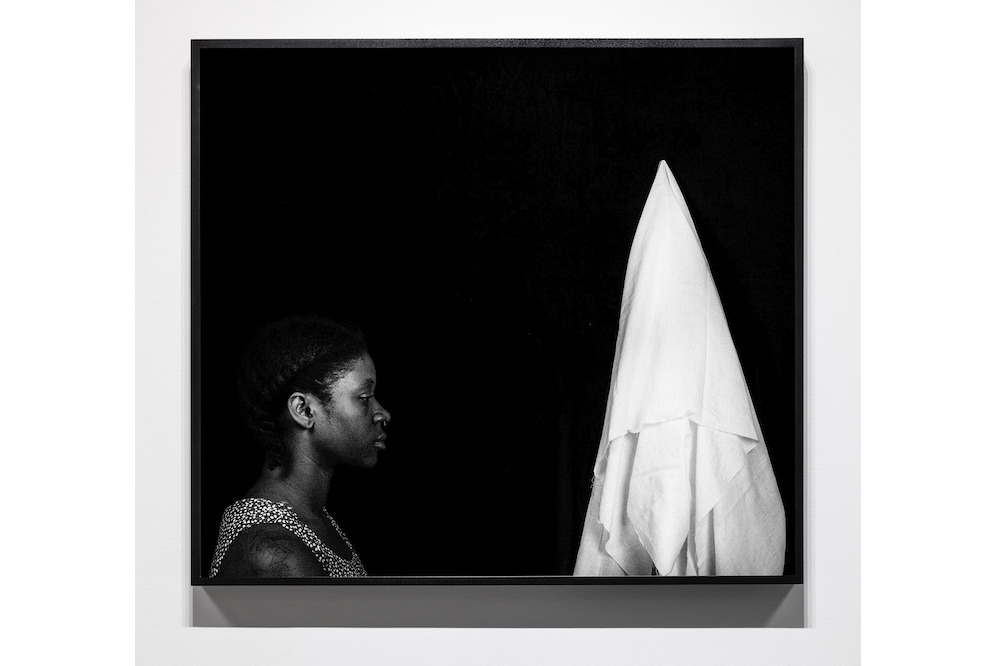

Anique Jordan, “Ban’ yuh belly,” 2019. Installation view at Zalucky Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

MPC: This is a tension that’s present for me in being a visual artist. I come from very different communities than you, I grew up in Trinidad, not exposed to contemporary art, and the gallery space is very foreign and intimidating to many of the people I would want to see my work. And to me it’s an ongoing issue of what does it mean to show in those spaces and not always have opportunities to have those audiences you want to see it. Having the chance to show at the ROM was such a different experience, because there were lots of black folks who came because they knew the exhibition was on, and came explicitly to see it; but there were also school groups and people who came to see the dinosaurs and stumbled across this work. And so that was a very special opportunity. A lot of people who wouldn’t have seen it in a more traditional “white cube” space, saw it. I think that the ways I work publicly — in terms of recruiting people, the process of working with communities — feels true to us, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the values of where the work will end up.

What has the audience response been like for this show?

AJ: I’ve had the two talks, and those were the times that I’ve been there with people viewing the work en masse, and it’s been a combination of things, both a quiet and heavy space. And in that way, a space of affirmation. I feel like a lot of the people I’ve spoken to, who talked through the violence they’ve experienced as youth workers, or as people working in the media, and watching these images of violence cycle in and cycle out, they say it’s a lot to contend with. There’s an image that’s representative of the KKK; an image that lists all the series of violence that have happened to the black body, those at the top of my mind. Putting those images right next to one another does something very frightening; it removes the veil. Because often times I feel like I’m living in a city where there’s this constant conversation happening like, “is this really Toronto? Could it really happen here?” And it’s like “yes.” How many times do you have to be like, “hello!” I think it was heavy and affirming; and being able to talk it through was healing. It allowed for us to talk it through.

MPC: That’s something we share in common because I was a social worker before I became an artist. And when I was first making this decision to go back to school, it felt like such a left turn, such a radically different way of moving through the world. And yet once I started making work I was like, “no I’m still doing what I’ve always done, which is working with people and their pain, and trying to create a shift for them.” I just do it with video and photography now instead of workshops and health fairs. [laughs]

I’m curious about photographing yourself. Do you consider it self-portraiture? I’m working on what I would consider to be my first series of self-portraits and so I’m curious what that process has been like for you.

AJ: Well because I’d entered into it feeling so heavy, I didn’t want to ask anyone else to step into that. I felt as though I needed to be the one to offer myself to be dealing with these ideas. But in the same sense, when I produce work as a self-portrait it’s also a type of performance. I don’t look at it as a reflection of me but as this performance. What it ends up asking me to do is ask questions of her, like, “who are you?” Or “how does she relate to me?” I don’t work in documentary photography so the image I produce is very much based on intuition, and a performative gesture. Once the image is captured I have to relate to it as part of me but also a step removed. In this context it helped a lot. It allowed me to have some distance. With these images, too, they’re all facing one direction and they’re never facing forward, never face the documents or viewer. You always get this profile. This character is never returning a gaze or directing you, she’s doing her own thing. Something about that is so healing. She’s going about her stuff, even while she’s contending with all this. Also having people come from Scarborough, where I’m from, seeing my face, it made it more approachable.

What has it been like for you, right now, switching from what you’ve been doing in the past to this portraiture?

MPC: My work has a performative element but I do consider it documentary. Lots of documentary makers use fictional strategies and staging, constructing a particular performance and entwining it in a “real experience.” But for me, there is a primacy on the production of affect. As a contemporary image-maker, I have to contend with a 180 year-history of a really negative visual representation of black people. So I’m always thinking about questions of black visuality: when, how, and where is it possible to see blackness? Because we can’t free ourselves from these other associations. They’re a filter you have to look through.

There’s lots of theorists who talk about the relationship between seeing and feeling, between affect and the way that photographs and images work on our body from an affective place. So my choices are always informed by this, and how performance is actually not separate from documentary. It’s part of that. But performance produces a different kind of affect in documentary.

In this project that I’m working on, I’m thinking about the relationship between my masculinity and the fact that I’m aging. I’ve always looked younger than I am, so now I’m asking, what does it mean to go from looking like a young black boy to a black middle-aged man? That means more risk in the world. It’s not good for me. Because even though black boys receive a huge amount of violence, youth is not as threatening to people as somebody who is seen as older. So this self-portraiture project is an exploration of what I would say was my queer boyhood, and now I’m aging out of boyhood physically – I’m now 46. In the past what I’ve done is work with people who share my intersectionality, and I’ve been able to tell my story through telling their story. But now I’m telling my story just through me telling my own story.

Anique Jordan is an artist, writer, and curator. Jordan works in photography, sculpture, and performance, often employing the theory of hauntology to challenge historical or dominant narratives. She has lectured on her artistic and community-engaged curatorial practice as a 2017 Canada Seminar speaker at Harvard University, and in numerous institutions across the Americas. In 2017 she co-curated the exhibition “Every. Now. Then: Reframing Nationhood” at the Art Gallery of Ontario. In 2017, Jordan was awarded the Toronto Arts Foundation Emerging Artist of the Year award. In 2018, she completed a residency at the University of the West Indies (Trinidad and Tobago), was the 2018-19 Artist-in-Residence at Osgoode Hall Law School, and the most recent recipient of the Hnatyshyn Emerging Artist award. Her work appears in public and private collections nationally.

Michèle Pearson Clarke is a Trinidad-born artist who works in photography, film, video, and installation. Using archival, performative, and process-oriented strategies, her work explores the personal and political possibilities afforded by experiences related to longing and loss. Based in Toronto, Clarke holds an MSW from the University of Toronto, and she received her MFA from Ryerson University in 2015. Clarke is currently a contract lecturer in the Documentary Media Studies program at Ryerson University, and she is a recipient of the Toronto Friends of the Visual Arts 2019 Finalist Artist Prize. Most recently, Clarke has been appointed to serve a three-year term as the second Photo Laureate for the City of Toronto.

1 Comment