In a recent essay for Artforum, Jon Rafman described his early work as “romantic.” Specifically, he cited his virtual safaris of Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (2008-2011) and the Google Street View screen-captures of his Nine Eyes project (2009-). His more recent videos and installations, he commented, “have a darker tone.”

Rafman’s eponymous solo exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM) – the first Canadian museum show for the Montreal-based artist (a shortlist nominee for this year’s Sobey Prize) following earlier solo exhibitions at the Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis (2014) and the Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2012) – confirms Rafman’s drift towards increasingly disturbing subject matter while demonstrating the persistent influence of Romanticism on his work. Through his frequent references to Romantic poetry and painting, Rafman continually presents himself and the subjects of his videos, installations, sculptures, and images as wanderers on a quest, exploring uncharted (virtual) territory in search of the Sublime, in the form of a lost ideal or a transcendent experience.

Rather than growing less Romantic, then, Rafman’s work has become Romantic in a different vein. What has changed in particular is the kind of sublimity that he and his imagined narrator-protagonists pursue. It’s telling that this exhibition – which is an early-career survey, though by no means a comprehensive one – doesn’t include any images from Rafman’s celebrated Nine Eyes series, for which he trawls Google Street View in search of striking photographic compositions accidentally produced by Google’s roving cars. The slow shift in Rafman’s body of work that this exhibition documents is largely a shift away from what he was doing with Nine Eyes, which was, until fairly recently, his best-known project. The transformation of attitude involved is also, as I will explain, representative of larger trends in internet culture and among Rafman’s circle of contemporaries.

When it launched in 2007, Street View was a particularly potent symbol of the convergence of the real world and its digital mediation through internet-based apps and platforms. Thanks to the wave of Web 2.0 technologies that rose to prominence in the mid-2000s, such as Youtube, Facebook, and the Google empire itself, the internet ceased to be (if it ever really was) a free-for-all playground for hackers, programmers, and nerds, and became a part of normal life for most people.

This is the juncture that Gene McHugh periodized as the post-internet condition, and it was in the nascent stage of the term that Rafman’s peregrinations through Google’s globe-spanning streetscapes captured some of the euphoria that accrued to the internet as a public space. The sense of the sublime that Rafman captured in this project wasn’t only inspired by the unexpected beauty of urban or natural landscapes (of which the series includes quite a few), but by the sense of limitless potential inherent to having so much of the real world so easily accessible for virtual browsing.

Of course, Nine Eyes also indirectly gestures at the problems posed by having such an enormous archive of images in the hands of a private corporation – all the blurred faces, addresses, and license plates on Google Street View hint at the Faustian bargain we’ve all entered into, trading the constant tracking and surveillance of our actions and environments for free access to information. Over the course of the last decade, grandiose promises about the internet’s potential to democratize politics, business, and culture have faltered. Though Silicon Valley suffers no shortage of utopian prophets, its credibility has been challenged by revelations regarding the extent of government and corporate surveillance, and by increasing evidence that the profits of the digital revolution have mostly accrued to a tiny (mostly white, mostly male) class of entrepreneurs.

This being the case, it might not be surprising that Rafman’s art has drifted away from investigating the factors that put the “post” in post-internet – the mainstreaming and ubiquity of digital technology, the collapse of any definitive break between the “IRL” and online worlds – towards more marginal web communities and subcultures where the fantasy of the virtual as an escape from real life still thrives. Rafman’s recent works blend images sourced from deviant and hedonistic micro-communities (furries, “crush” fetishists, hentai) with a poignant sense of nostalgia for the visions of the future offered by previous eras.

It’s fitting that the first works that a viewer encounters in the MACM exhibition are videos drawn from Rafman’s Kool-Aid Man in Second Life project, presented in a viewing installation composed of a glass box with a built-in chair and integrated speakers – one of a number of custom installations produced for this show in order to display Rafman’s video works, most of which are available online. In retrospect, Nine Eyes (2009-) and Kool-Aid Man (2008-11), both of which were initiated around the same time, represent a crossroads in Rafman’s practice. Both involve the artist on a journey of exploration through virtual worlds, but where Nine Eyes raises questions about the politics of visibility, about surveillance and data ownership, and about the status of photography in a world of image excess, Kool-Aid Man has more to do with the psychology of gratification enabled by the internet. The latter is a quasi-ethnographic and often voyeuristic catalogue of the wildly varied pleasures and fantasies invented and pursued by denizens of the web’s murkier corners. Needless to say, the path suggested by Kool-Aid Man is the one that Rafman’s more recent work has followed.

Wherever Rafman’s Kool-Aid Man avatar goes in Second Life, he finds environments and other avatars apparently created for the sole purpose of having weird sex – or at least some facsimile thereof. Watch as Kool-Aid Man encounters a male figure in baggy jeans and a bucket hat masturbating a recumbent unicorn, or as he observes a hermaphroditic centaur mounting a fox-humanoid from behind, or as he approaches a fire-breathing, three-headed dragon in a torch-lit castle (a moment’s hesitation, a hint of relief – has Kool-Aid Man finally encountered a legitimately majestic creature?) only to see the dragon get up on Rafman’s avatar and start humping it. One has to wonder what kind of satisfaction Second Life users were really deriving from these crudely-animated sex acts. Not to belabor the obvious, but CGI models don’t experience pleasure, and making it look like they do takes a lot of effort – a fact that becomes more clear when Kool-Aid Man visits the “Pompeiian Delights Sex House,” where the walls are plastered with pixelated ads for 3D-rendered body parts, animations, and sound effects to make one’s virtual sex experience more lifelike.

It’s not all quite so sordid, though. As with Rafman’s Google Street View images, Kool-Aid Man’s journey through Second Life is punctuated by as many moments of surprising beauty and meditative reverie as absurd or pathetic spectacle. Half of what makes the project so intriguing is how often those two poles co-exist – parody, nostalgia, and celebration are virtually indistinguishable in this, as in many of Rafman’s works. Consider, for example, Kool-Aid’s Man happening upon a synchronized dance routine, performed by furries, goth-raver avatars, and a blue-skinned Na’vi, all the while set to Darude’s 1999 trance hit “Sandstorm.” The patent absurdity of the scene crosses over into touching pathos: a lot of work went into crafting this moment of strange togetherness. The figure of Kool-Aid Man himself (itself?) condenses these contradictory aspects as a commercial mascot from Rafman’s childhood (and my own, I should add, since we’re more or less the same age), noted for peddling a cheap, sugary drink with outrageous party attitude. Contrasted with the more adult situations through which Rafman pilots his protagonist, however, Kool-Aid Man’s blankly euphoric grin and goofy dancing animation take on a beatific innocence, uncorrupted and eternally enthused.

The same glass-case installation that screens Rafman’s Kool-Aid Man videos also displays a few of his other stand-alone videos set in virtual worlds, such as In Realms of Gold (2012), which borrows its title from a poem by John Keats. The video distills excerpts from a first-person shooter in which no combat action occurs, giving the viewer a chance to luxuriate in the lifelike renderings of landscape features, foliage, animals, and atmospheric effects. It’s one of Rafman’s most straightforward statements that, within virtual worlds traversed by gamers or internet users, an experience of sublime beauty is possible. Woods of Arcady (2010-12) juxtaposes a text-to-speech reading of W.B. Yeats’s poem “The Song of the Happy Shepherd” – its first line: “The woods of Arcady are dead / And over is their antique joy” – with footage of classical statuary and architecture in Second Life, carrying the more ambiguous message that virtual archives allow access to historical information and experience while, at the same time, the sheer volume and availability of such information dilutes any possibility of legitimate historical consciousness. Technology provokes a futile quest for an imagined, authentic experience that is ultimately unrecoverable, and attempts to recreate it produce only travesty.

In Kool-Aid Man in Second Life there is another layer of nostalgia that has to do with the datedness of the platform itself. Launched in 2003, Second Life was already a bit passé by the time Rafman began exploring it in 2008. Though its user base peaked around 2009, its graphics have remained at a fairly clunky 2003 standard. More importantly, its free-for-all ethos is closer to the cyberpunk future imagined in the 1990s than to the mundane, contemporary reality of social networks exemplified by Facebook’s “real-name” policy. Despite the sensationalism of much of Kool-Aid Man’s content, the project is pervaded by a sense of loss and melancholy provoked both by the relegation of the utopian dream of a virtual world to the fringes of internet culture, and by the thoroughly abject ends to which this technology (and the imaginative resources of its users) has been employed.

As Rafman has gravitated towards extreme internet phenomena, the utopian sublime of his earlier work, characterized by outward exploration into the promising expanse of new virtual territory, has shaded into a more dystopian sublime, plumbing psychological depths rather than geographic space. In a series of videos including Still Life (Betamale) (2013), Mainsqueeze (2014), and his new Erysichthon (2015), Rafman has trawled the message-boards, forums, and video channels of the deep web to create disorienting and often difficult-to-stomach collages of deviant imagery. In this exhibition, Still Life (Betamale) and Mainsqueeze are both presented within a blue vinyl “pit couch” installation reminiscent of viewing architecture that Ryan Trecartin has used to display his videos – which makes sense, given that both artists aim to give form to the sometimes pathological mutations of selves squeezed through digital networks.

Still Life (Betamale) was conceived as a collaboration with electronic musician Daniel Lopatin (a.k.a. Oneohtrix Point Never). Through images of scum-encrusted keyboards, dank computer dens overflowing with empty bottles and tangled wires, and clips of 8-bit anime and furry fetish porn, the piece evokes the figure of the troll whose total immersion in the internet has left him sexually stunted and socially alienated. Mainsqueeze is broader in scope, juxtaposing a wide range of obscurely troubling video footage (a washing machine spinning itself to pieces, a woman crushing a live shellfish under a spiked heel) with art-historical images of violence and depravity, suggesting the ahistorical continuity of a human (or perhaps inhuman) drive towards entropy and debasement.

Rafman’s new video, Erysichthon (2015), here displayed inside a darkened, enclosed cabin with a vinyl floor and mirrored walls, brings this tendency to a fevered pitch of poetic intensity. The piece is named for the mythical Greek king of Thessaly who was cursed, after cutting down a sacred grove, to a hunger so all-consuming that he eventually ate himself. Though the imagery itself is more oblique than Betamale or Mainsqueeze (a cube being absorbed by black sludge, fingers incessantly swiping screens, a snake in a dish eating its own tail), its piercing soundtrack and disturbing voiceover conjure a mind pushed to its limits, reiterating that it has seen too much. “If you look at these images long enough,” it intones, “you begin to feel that you composed them.” And, at another point: “They corrupt me so. Is it too late?

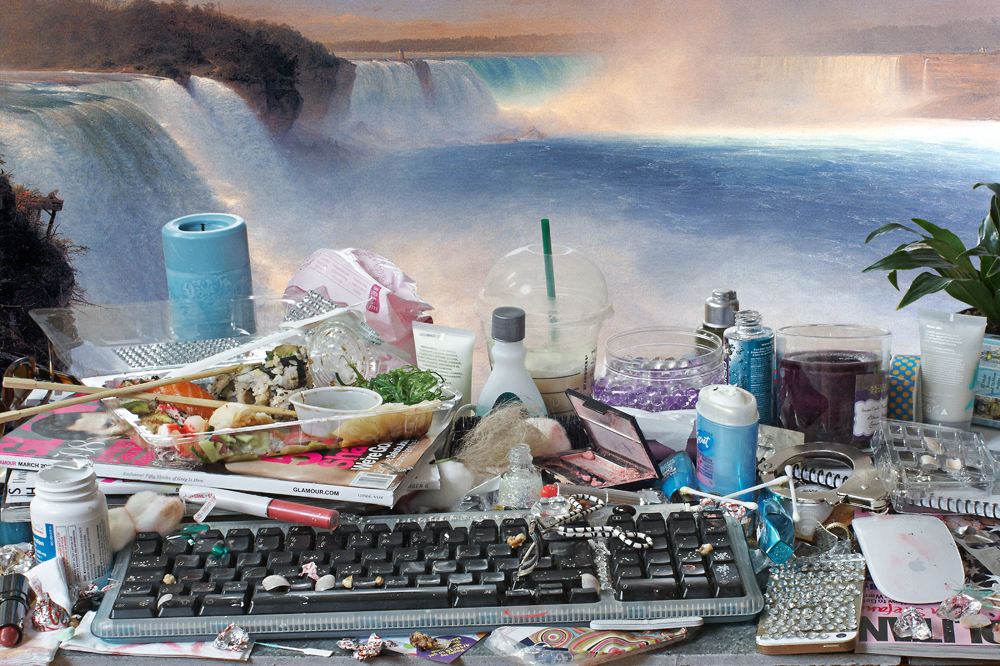

Displayed around these videos and continuing throughout the rest of the exhibition, Rafman’s new series You Are Standing in an Open Field (2015) offers another visual metaphor for the correlation between virtual escapism and physical abjection. Throughout a number of large-scale photographic prints, Rafman stages juxtapositions between cluttered keyboards (each one “themed,” in a way, with its own personality, whether it’s glamor mags and makeup, or energy drinks and anime colouring books) and, in place of a computer screen, appropriated landscape paintings from the Romantic era and Hudson River School. The further twist is that the surface of each print is splattered with translucent resin, suggesting either ejaculate or a glaze of spilled soda, functioning in either case as a gross materiality that blocks access to the hoped-for sublime, or the by-product of actually finding it. The quest for transcendence, Rafman implies, despoils its object rather than ennobling its subject.

In focusing on the perils and pathology of approaching the internet as an escape from physical reality or the real social world, we might wonder, however, if Rafman is missing out on the more pressing – though less sensational – aspects of what digital technology means for average users. Rafman has asserted, however, that “the more marginal, the more ephemeral the culture is, the more fleeting the object is … the more it can actually reflect and reveal ‘culture at large’.” The parable of Rafman’s Erysichthon, for example, might reflect that even the most casual internet use is governed by a network logic which demands that our attention spans keep up with the speed of digital communication: new emails in the inbox, more tabs to open, more comments to respond to, posts to like, notifications to check. We may not all have seen too much, but we are all faced with the anxiety-inducing fact that there is always too much to see. The more of it we try to access, the hungrier we become.

The other question that emerges from Rafman’s trajectory is how much further can he mine this vein? The voiceover of Erysichthon repeatedly invokes a dead end or a point of no return. The last two major video works in the exhibition, Remember Carthage (2013) and A Man Digging (2013), are both film essays sourced from video games (Max Payne 3 and Uncharted 3, respectively) in which the narrators seem to come unmoored in time, and ultimately get lost, or lose themselves. Is Rafman similarly hitting a dead end? Or has he lost his way?

In the same essay I quoted earlier, Rafman stated that he’s fascinated by the darker manifestations of internet culture because he sees them as a by-product of the lack in contemporary society of a “viable or compelling avenue for effecting change or emancipating consciousness.” He writes: “the energy that once motivated revolution or critique gets redirected into strange and sometimes disturbing expressions.” Without a belief in any redemptive, transcendent, or even effectively critical function for art, however, one wonders what motivations remain to fuel an artistic practice. Rafman has also confided that his own artistic process mirrors that of the trolls that he portrays: “[It] begins with surfing the internet to the point of sickness, where it feels like I’m about to lose my mind sitting in front of the computer for so long.” Simply put, can he keep it up? Should he?

A number of Rafman’s contemporaries have recently made public renunciations: Jennifer Chan tweeted “Postinternet: I renounce my intellectual contributions to this colonial movement. It’s been a massive ideological jerkoff.” Nik Kosmas of AIDS-3D quit making art in order to focus on bodybuilding and his matcha tea business, declaring, “I just didn’t think there was a point or a respectable future in endlessly critiquing or arrogantly joking about innovations coming from other fields.” Jaako Pallasvuo decided to stop uploading. And in a talk given in Montreal this April, trend-forecasting collective K-HOLE declared “burnout” to be the next big thing: the ability to go off the grid and enforce your own privacy is now a potentially expensive luxury, a status symbol. Some might strategize a “weaponized burnout,” calculated to keep their audience hungry, while others might experiment with “lifestyle burnout,” downgrading (or outsourcing) their internet presence for their own well-being.

It may be that post-internet art itself is burning out. In Lucy Lippard’s canonical account, Conceptual Art – at least in its first, focused, capital-C/capital-A iteration – lasted six years (1966-1972). Post-internet art, if we date it from 2008 (when Marisa Olson allegedly coined the term) or 2009 (when Gene McHugh started his blog), has lasted about as long. Of course, it was only after the end of its first phase, and the termination of the more radical aspirations associated with it, that Conceptual Art was canonized, its higher-profile practitioners safely integrated into the gallery system, and its influence distributed as a more diffuse form of small-c conceptualism.

It is likely that we are nearing the end of the breathless first phase of the artworld’s reckoning with the hegemony of the internet, and the long-term fallout may well follow a similar trajectory. For one thing, post-internet artists are getting solo museum shows now. Jon Rafman’s work has been some of the most provocative and popular of post-internet art’s initial wave, and he stands poised at the cusp of, potentially, much greater commercial and critical recognition. But the long-term reception, relevance, and viability of post-internet as a category remains uncertain. If Rafman levels up, he could rise above the label, or cement its respectability, or define what comes after. At present, though, Rafman appears to be more concerned with drilling down than rising up. In his latest work, the future appears as a yawning void rather than a promising vista – though still sublime in its own way. Whether this image is what the age ultimately demands will largely depend on how the age appears, once we’re looking back.

4 Comments