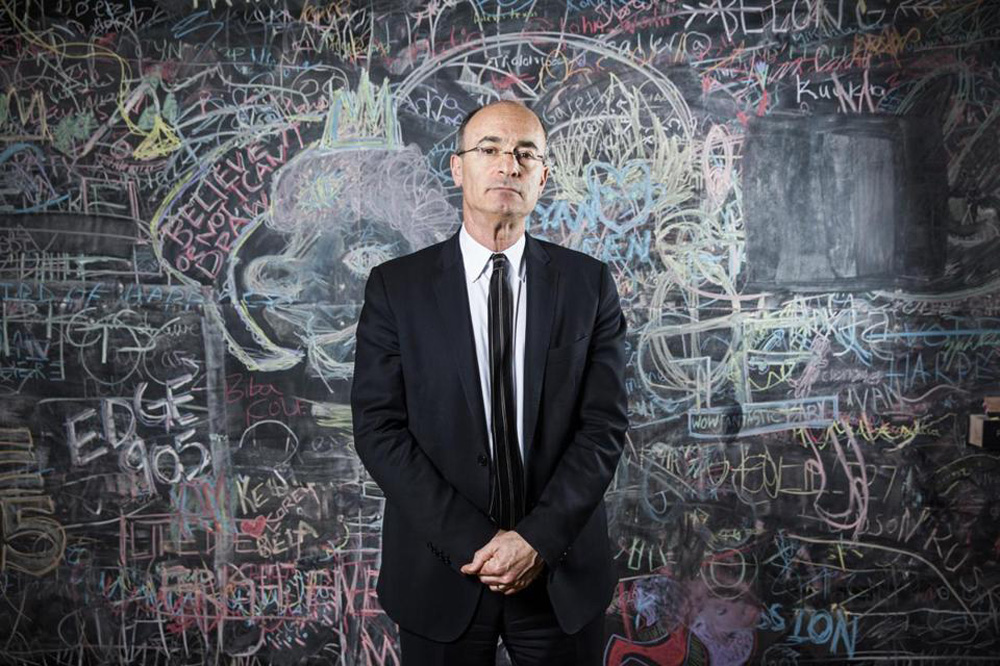

June 26, 2015 marks Matthew Teitelbaum’s last day as the director and CEO of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). His departure caps 22 years at the institution, and 17 years in the director’s chair. Five weeks later, Teitelbaum will begin a new appointment as director of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, an institution in a city where he lived and worked for a brief time years earlier, in the role of curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Teitelbaum is being anticipated in the Boston press, with a recent feature describing him as “a 59-year-old Canadian who combines admirable conscientiousness with a bright, disarming smile, and a well-placed confidence in his ability to charm almost anyone.” Clearly, he’s less running from something than walking forward.

Jennifer Matotek, director/curator of the Dunlop Art Gallery, spoke with Teitelbaum about his departure, framing the conversation as one between colleagues. She asks after how the AGO has transformed during his tenure, and, while he hesitates to discuss his vision for the Boston MFA, Teitelbaum is willing to consider the challenges and successes he’s fielded at the AGO, and the issues he sees for its future. Among them, he wonders how it can become an internationally recognized museum, and maintain a stable yet responsive identity amidst the increasingly malleable mandates of fellow cultural institutions. He asks, too, how it can create programs that are visitor-centric without deviating from the museum’s institutional expertise. He is, at this time, reflecting on quite a lot.

Why was now the time to leave the AGO and take this opportunity in Boston?

There was not a single thing that pushed me from Toronto or made me think I needed to find something else. And then I got a call a few times from Boston, saying would I meet with them, and I said no. But then at a certain point, a few things happened, and I decided to meet with them. And I went down there, really liked the people I met, got excited about the possibilities the collection allowed. It started with the notion of the collection, and then I realized I could be comfortable here, and that I could be challenged as well. Once that started to happen, then my next question was does the institution want to change, is it clear to them what they feel some of the next steps might be. And there was a lot of energy and enthusiasm around some of the conversations we were having about what could happen. There was nothing about Toronto that felt tired, or over with, or too conservative. On the contrary. I feel like I’m leaving Toronto at the moment where there is extraordinary possibility. And I think other people are feeling it, too.

What legacy are you the most proud to leave the AGO with?

That I’ve helped create a culture where people are working as hard as they are because they believe in the power of art to change lives.

What do you want to change at Boston MFA?

I don’t know, precisely. I don’t know enough to know what has to be changed, yet. All museums have a continual desire and obligation to articulate their relationship to their city and complexity. I look forward to doing that at the MFA.

How has the AGO as an institution expanded over the years you’ve been there, since 1993, and director since 1998, apart from the obvious physical changes to the building?

I think around 2006, two years before we reopened (after the Frank Gehry redesign), people would have noticed we were becoming a more visitor-centered organization. And then about three years ago, people would have seen us collaborate more, partner more, give up our authority more in order to create new relationships. You would have seen that as an increasing thread in the way in which we talk about things. So I would say that the key changes were, one, that moment we understood the visitor to be the center of what we’re doing; and, two, that way of working where we give up our authority. The culture followed the rhetoric – the rhetoric that said “let’s start doing things this way, let’s reposition ourselves.”

Tell me more about how “giving up” authority or power is critical to collaboration and partnership. How have you delivered on this?

It’s all a work in progress. We’ve had things we’ve clearly been involved with, with partners in developing ideas. Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time is a good example of this, where we’ve worked with the community and a consultation group, and probably worked more closely with them than any previous group we’ve ever pulled together.

How do you think you could have delivered on this better?

I think when we’ve done things like this well, we’ve discovered quickly how powerful it is, in terms of getting to the right idea, but also in terms of creating audiences. When we think about how we build audiences, and loyalty and fidelity with your institution, building programs to attract audiences, and having those audiences be your advocates is really important. It’s not just about the object or product you create. It’s also about the way in which energy is galvanized in a place.

Do you have an example of a situation where perhaps you didn’t succeed with audience engagement?

With Ai Weiwei, it was an important show, and we presented it well, but I don’t know that we embedded a sense of anticipation, or a sense of personal-identity stories, as well as we could have.

How has the increased push to audience engagement, via education and marketing, changed the focus of your intentions for the institution over the years?

That’s a really good question. When I look back, I think one of the things we got right was balancing what I would call a research agenda with a popular-engagement strategy. I don’t think we sacrificed one in service of the other. We were therefore at once scholarly and populist, both specialized and broad. We did a pretty good job of finding that balance. I think that too often there is a narrowing and a choosing between one identity or another and I think that distinction’s often been made too early.

Has it been your vision, then, to house more generalist collections at the AGO?

I wouldn’t go there. I would say that I think the way we have to go is presenting a broader set of objects and ways of thinking about what art is, and be accountable for it, but be a little riskier in the kinds of things that we show.

Can you give me an example of what riskier might look like?

I think David Bowie was risky.

I agree.

We did it out of a very strong conviction, and that conviction we wanted people to think about whether Bowie could and in fact did create himself as a work of art, and if, in fact, that proposition is even possible.

I admit, I was working at TIFF at the time, and I thought it was a bit strange, because it seemed like the kind of thing that TIFF might show. Seeing it at the AGO was interesting. However, if all the institutions in Toronto are showing similar things, do you worry about the implications of these places no longer having unique identities?

I do worry about it. I worry that it is very confusing for audiences. On the other hand, one doesn’t want to be arbitrary and say “this shall be this way, this shall be that” and be stubborn about it. We live in a world where categories are breaking down and there is overlap.

I think when we work against what I call “learning styles,” [we do it] at our peril. If we see new audiences are blurring boundaries, making connections between things in ways we didn’t expect, the notions of category and exclusivity at museums is probably under question … “We collect totem poles, you collect soapstone; you collect red things, we collect blue things.” I think things are much more interdependent than they’ve ever been. But I do worry about blurring boundaries because I don’t think all institutions can do all things well. You see times where institutions have done things where this is truly stretched. A lot of this is stretching into contemporary art, let’s be clear about this, because people want some of that sort of excitement. I worry that (institutions) may be taking on things, and not doing them well.

As a fellow museum director, I know we have two jobs: serving artists, but also, serving the public. It’s challenging to treat these two issues and groups as though they are separate. How do you feel you have managed this real or imagined hierarchy at the AGO?

I feel that the two are not comfortably separable. They are tied. One of the primary focus points of my job is to create audiences for artists. My role is to create an environment in which people become the audience/viewer in part because I’ve helped to create that. I’m thinking a lot about different ways in which that can be created. At the same time, I’ve never lost the sense that one has to see the world through the eyes of artists. You’re invested in the experience/pleasure of running a museum not because you want to be a closed academic institution that has narrow and inapplicable expertise. You do it because you want to convince people that what you’re doing is important.

I’d like to ask you a question about leadership, because modeling and fostering a strong directive is clearly important to you. What are your hopes for the future of art institutions in Canada?

One of my hopes is that folks like you understand the power of networks and exchange systems. That you can all integrate with other institutions more broadly on the world stage… in China, Europe, and the United States. You can become an advocate of artists in an important way.

You’ve said in the past that the AGO has to get to the point where it is seen as a “truly great museum.” In your opinion, what should AGO’s next steps be to achieve the goal of being seen as a truly great museum?

I think there’s a culture piece. Staff needs to be encouraged to travel, to reach out, to connect in the spirit of partnerships. It cannot be an insular institution. And then, you want people to be comfortable, and you need to hire and encourage people you work with in ways that communicate how the AGO is a good partner, and to really push people out so there is a recognition that relationships build the program. The program doesn’t start with some brilliant insular insight and then get realized in isolation. No matter where an idea starts, you have to realize it in partnership with others. Push that out, raise your sights, make your relationships international – make sure your voice is heard.