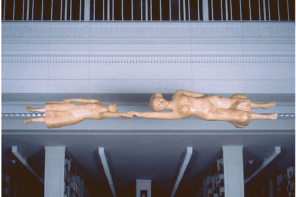

The erection that introduces Baselitz: Six Decades seems an appropriate prelude to what follows. That it protrudes like Pinocchio’s nose from a disproportionately small figure who appears dead, prostrate on a table, is even more fitting for the start of a retrospective celebrating an artist whose work is often both lifeless and obtrusive.

In honor of Georg Baselitz’s 80th birthday, Six Decades highlights over one hundred works from the German artist’s prolific career. Traveling from the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, to its current residence at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, the exhibition starts with The Naked Man (1962), which established Baselitz’s image as a provocateur. In a polemic against the survey, the Washington Post’s Sebastian Smee argued that Baselitz’s enduring success is the result of a stubborn art market unwilling to distance itself from an artist in whom it has invested too much. Smee’s critique is gratifying, but it doesn’t broach the more pressing (and related) issue of Baselitz’s unyielding disdain for women. On multiple occasions, the artist has asserted that women painters “do not pass the test.”

“The market doesn’t lie,” Baselitz explained in an interview for the Guardian in 2015. “… it’s a fact that very few of them succeed. It’s nothing to do with education, or chances, or male gallery owners. It’s to do with something else and it’s not my job to answer why it’s so.”

He was correct in thinking it’s not his place to speak further on the subject. But he went on:

“If women are ambitious enough to succeed, they can do so, thank you very much,” he continued. “But up until now, they have failed to prove that they want to.”

However flimsy a determinant of actual quality, exchange value is the most tangible indicator of Baselitz’s own worth as an artist. For Baselitz to use sale records to substantiate the inferiority of women artists is about as insipid as the art market itself. Still, a dull knife is dangerous.

Organized in chronological order, Six Decades indicates how, after Baselitz returned from a Florence residency in 1965, his Heroes and Fracture series laid bare the alienation and division that defined post-war Germany. The paintings disrupted myths of national identity with abjection and vulnerability (through less trite means than his early motif of postmortem erections), and represented a solid effort that established his place in the artworld for decades to come. But this security proved corrupting. Writing on the last Baselitz retrospective to take place in the US, Roberta Smith concluded, for the New York Times: “A dismaying number of his recent works seem simply dashed off, as if the artist expects everything he touches to become an instant masterpiece.” That survey took place at the Guggenheim in New York in 1995 and subsequently toured to the Hirshhorn. Six Decades returns to that venue with over twenty additional years’ of paintings and sculptures, and proves that his work has remained stagnant. The resounding dullness is interrupted only by audio reverberating from Does the body rule the mind, or does the mind rule the body?, the Hirshhorn’s first-ever exhibition of performance art (notably featuring all young artists who identify as women, queer, and/or people of color), installed via video documentation and live performances in the space on the other side of Baselitz’s imposing canvases.

Since the 1970s, Baselitz has routinely turned to gimmick. This is most evident in his “inverted” paintings, which make up the majority of the work on display in the exhibition. Adopted in 1969 and maintained as his go-to trademark, Baselitz paints his subjects upside down as a means to “question the subservience of the painting to the image” (as the wall text describes it). In other words, Baselitz sought to drain the image of implication, which seems futile as an approach, given that a figure painted upside down still bears all the narrative, historical, and social attachments that are irreducible from figuration. Further, Baselitz’s aim conflicts with his apparent love of motif and appropriation: he frequently incorporates elements of traditional German, African, and Christian imagery in his work. These associations are no less perceptible when flipped. And if the artist intends to hierarchize the material painting over its subject, we might expect more from his use of the medium; his haphazard application and color sensibility come across as more negligent than anarchic or spontaneous.

Effective or not, stripping a subject of meaning or identity is akin to dehumanization. As it happens, Baselitz seems to do this with greatest effort and effect when painting women. He debases his male subjects too, though less consistently, pausing for reverence in his painted homages to men like Antonin Artaud, Edvard Munch, and Otto Dix, while recycling his own iconography in the self-referential Remix series of the early aughts.

Baselitz frequently paints his wife, Elke, whose role in his work, beyond modeling, is explored nowhere in the generous wall labels and biographical timelines, despite the fact that she served as his studio assistant and was a constant presence throughout his career. In two nude portraits (Nude—Elke, 1974; and Bedroom, 1975), Baselitz paints her upside down in cruddy, dead greys, seated in a richly-colored room. In the latter portrait, she sits side by side with her husband, who also appears nude, but in more vital tones reserved for the living. He applies richer hues to the nameless woman of Finger Painting—Female Nude (1972), though here his palette appears overworked, lacking the (albeit sometimes misplaced) confidence that marks his painting style. The figure’s muddled abdomen, framed by tan lines around her breasts and genitals, is centered on the canvas with her feet cut off by the top edge and her expressionless face dangling toward the bottom. Were it better painted, the image might bring to mind Titian’s Marsyas, hung from his hooves to be flayed.

More unsettling is the upended woman at the center of On the Right and Left a Church—Jörg (1987). Though she is clothed, Baselitz illuminates her genitals in a sickly yellow, and much like his hero, Willem de Kooning, renders her breasts like the cartoonish balloons of a twelve-year-old’s doodle, and her face as a grotesque mask. If she didn’t look enough like a carcass hanging in a butchery, Baselitz applies bright red in streaks spilling from her body and in bullet-like dashes flying horizontally through her legs. The bizarre sexualization compromises the painting’s potentially powerful allusions to wartime chaos, suggested by the curiously upright churches, which appear fractured and possibly aflame.

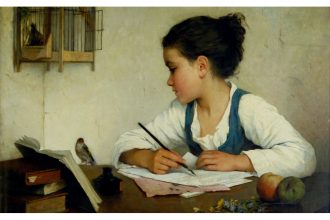

Little has been made of Baselitz’s casual defilement of women in his work, perhaps in part because his politics have come to light so late in his long career. And, as Mira Schor wrote in her searing 1986 feminist critique of David Salle (a star of the notoriously gender-exclusive Neo-Expressionist movement that Baselitz helped to generate), “to condemn that content is to betray a misunderstanding of the whole purpose, which seems to be a continuation of a male conversation that is centuries old, to which women are irrelevant except as depersonalized projections of a man’s fears and fantasies, and in which even a man’s failure is always more important than a woman’s success.”

There is nothing profound about the misogyny Baselitz exercises in his words and in his paintings. The same might be said of his nonchalant flirtation with fascist gestures in his massive wood-carved figure Model for a Sculpture (1979-80), which he defended at its scandalous Venice Biennale debut by claiming the apparent Nazi salute was cribbed from an African artwork. (Needless to say, a white artist’s appropriation of African imagery is not exactly an absolving raison.) Canonical male artists, especially figurative painters honored by museum retrospectives, have come away with much of the same in the name of a putatively greater objective. The difference is that this retrospective is displayed not only in close proximity to a White House currently occupied by a man whose own blatant sexism and fascism have been normalized to disastrous effect, but in a public institution operated by that man’s government. Like Trump, Baselitz’s view of women is not only tolerated, but rewarded.

Alternative headline? „A short, shallow review“ tendentious in argumentation, low level research. Why do so many women need to be that misandrystic for their own well being? We women deserve more than pseudo feminist propaganda. Not clever this at all.

PS: it is well known that Georg and Elke met as fellow students at the academy before marrying and she was never his assistant as claimed here. She is also known for having a strong personality

Markus Lupertz, Anselm Kiefer, and other post war German artists incorporated Nazi symbols and imagery into their work as a sort of exorcism. Baselitz did the same, but the author apparently missed it. Instead, she focused on 40-year-old misunderstanding of his work. Back then, the German public also accused Kiefer and Lupertz of having Nazi sympathies. We can now see how absurd that was. It’s way past time to understand Baselitz’ work, too. And, the critique is ludicrously transparent in its efforts to find misogyny in every image. Yes, his images are messy, slashed, inverted — all of them, women and men. There are metaphors aplenty; the author didn’t see them.

The only strength this person’s art seems to have is that he is able to paint upside down. Whoop De Doo, frankly. Not worth an article.