In the movies, we are accustomed to watching the main character navigate the edges of a party, fall into a moment of introspection, receding into a quiet corner of their mind. A voice-over might ask: “is this my life?”, “where am I going?” Typically during these withdrawn moments, the face is depicted like a loaded, blank surface – what is normally a communicative portal becomes an unmistakable barricade.

The face is a constant fixture in Valérie Blass’s work, but one transformed, veiled, or absent. Blass, a mid-career Montréal artist, is known for producing disturbing, morphed creature-objects, complex assemblages that bring to mind the similarly surrealist dreamscapes and sci-fi nightmares of Shary Boyle and David Altmejd. While Blass has previously alloyed historical and contemporary references, her recent sculptural assemblages, on view in My Life at Daniel Faria Gallery, hones an inner, psychological space. Like self-obsessed, needy bloggers, Blass’s subjects seem vulnerable, immersed in self-examination, as they sit naked (or almost naked) in front of mirrors, or bend over undressing. Here, bodies are rarely presented as complete wholes. There is always a part missing, hindering proper function, impeding clear and effective communication. Impressively, while these beings seem awkward and foreign, their incomplete, self-absorbed make-up should be familiar to us. After all, they reflect our mediated, constantly disrupted, and rarely fulfilling contemporary experience.

What is missing, or what has been replaced, proffers the most interesting and most desired part. Blass masterfully, slyly slips in replacement objects and images which hide their own history or function while successfully performing an assigned role. Consider for instance La mépris (The Error, or The Misunderstanding, 2015), a black velvety bust that is placed in front of a large concave mirror. Composed of two objects covered in flocking, a torso supports what is actually a porcelain cat suited up like a theatrical prop to stand in for a head. In the mirror, the nose (or the cat’s tail) dominates the reflection, staying central, while the upside-down gallery spins around it. The reflection of the viewer, on the other hand, is completely absent, (until you lean in and suddenly your giant distorted face fills the background). Dr. Mabuse Psychanalyste (in French, a word-play on “doctor abuses me,” 2015), a cast sculpture of a woman dressed only in pink underwear, stares into a concave mirror. She sits in a stiff, uptight pose on a plinth, her knees almost touching the wall. But her reflected face seems strange, disproportional, perhaps warped by the mirror. Only with some effort, looking directly at the face, does it become clear that the front of her head is sliced off and switched with a tiny surrogate, a pasted-on visage. This is a face like a mask: disposable, rigid, always smiling. It can only be worn one way.

Supplemental body parts, synthetic limbs, and hair extensions are all a common sight, here, and the skin is comprised of a pasty modeling clay or completely covered in black, taut fabric. The exhibition feels like a backstage tour of a set being used for an unknown performance; we explore intimate scenes, peek under draped long hair, hover over bare shoulders. Consequently, what is most guarded, like personal belongings, private space, or moments of self-analysis, are left exposed. In these frozen scenes of introspection, I was a little disappointed to find pipes, mirrors, naked eroticized bodies, and the ubiquitous sexual acts that we’ve come to associate with analysis on the therapist’s couch. Many other artists (from René Magritte to Jake and Dinos Chapman) show an interest in reconstructing the body in a perverse, sexualized manner. But what is unexpected and impressive in Blass’s work is how once these items are composed together, the body becomes not only the aggregate of parts, but a tense, psychologically-charged unit; an assemblage of fears, pleasures, and desires.

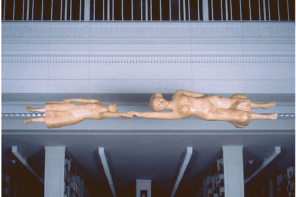

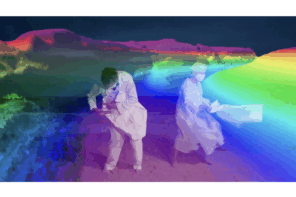

As the animate and inanimate, corporeal and incorporeal, share a stage, they seem to be handled with the same brush, perhaps a brush of indifference, which leaves everything bare, hanging dangerously. In Sois gentile (Be Nice, 2015), for example, two figures, barely balanced on a very narrow, phallic support, share a moment of passion. Like hardened drips of metal, their bodies seem to be melting or emerging, fixed horizontally to the wall like a swung-open gate. The question becomes, does the inert object animate the body or does the body animate the object? Surtout ne pas consulter les ingénieurs! (Definitely Don’t Trust the Engineers, 2015) is a collapsible cut-out sculpture made of wood, loosely based on a human form. Featured in the stop-motion animation rien à redire (Nothing to Retell or Repeat, 2015), this awkward figure is fastened by a long beam to a dancer wearing a tight, black body suit, whose actions it mimics crudely. At first these movements resemble a master training their monkey, but as they become more jerky and repetitive, they also invoke something harsh and provocative, eventually emulating oral sex.

As in all provocations, one looks for the culprit, but just as the body parts here are arching, stretched, promiscuously posed, they are, too, sexualized and utterly enticing. The objects featured in a series of photographs titled Vices (2015), appear strangely anthropomorphic, and are themselves associated with addictive, pleasurable activities. Each is slickly presented (as if in an advertisement), in the grasp of a hand wearing a glittery, black opera glove. In Vices – pavaner (Vices – Strutting About), the fingers are positioned strategically around a ball-shaped part of the object, presenting it in full view, while its bottom half is left dangling, about to slip out of the sensual grip. The elongated fingers point to the viewer, as if caught in the act of taking or giving. The fingers in Vices – épater (Vices – Showing Off) point up, gently balancing a glass bong, a device that is often shared, and whose usage is ritualistic. On a small ledge, protruding from the bottom of the photograph, a cigarette holder stands vertically on its tiny base – a remnant of a party, perhaps – left by the artist as a small offering to the passerby.

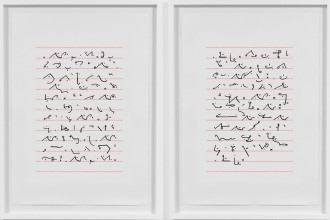

The objects displayed in Vices appear like precious items found at secondhand shops. All are available, accessible, yet locked in the austere and insubstantial space of an artwork. This leaves us in an uncomfortable state of wondering, “are we invited guests or are we the intruders?” Walking down the street today is to be inadvertently included in personal cellphone conversations; while in cafes, laptop screens project glimpses of strangers’ private lives. One looks, but then feels guilty for doing so; it becomes difficult to know when we’re being addressed. In a small publication by Maryse LaRivière (based on a true story that happened to Blass), The Sun (2015) takes this idea to an extreme. The narrative (structured like a dialogue) has the protagonist waking up and brewing coffee, when she notices a puddle of urine on the floor and more shockingly, a naked man sleeping in her bed. She says: “How did this handsome young man end up naked in my bed? I didn’t bring anyone home last night. I mean, I barely even slept last night.” Retracing her steps does not help; panic sets in; she is afraid to wake him up or even to document the event by photographing him. She is no longer in control of her memories or of her private space; how is she to communicate with an unconscious body?

At the heart of this exhibition, Blass considers whether communication is even possible, when somehow every attempt at communicating, being included, addressed, ends with resignation, humiliation, introversion, or alienation. What recourse is left? In the last moment of The Sun, as the protagonist embraces her lover immersed in a warm pool of shared urine, it seems that the only resolution available to really touch, really communicate, is through the most profane and basic functions of the body – which assert that I am here, and I will be heard, and this is who I am. There is no misinterpreting this.