In January of 2015, Hito Steyerl ventured to the border between Turkey and Syria while the battle for Kobanê – a harrowing struggle between Islamic State (IS) militants and a coalition of Kurdish and Syrian forces – thundered a few kilometers across the frontier. Steyerl visited the region to research one of the world’s oldest ritual sites, the Göbekli Tepe complex, but became a spectator to a conflict widely circulated and discussed on the Internet: Syria’s brutal civil war. “On the border with Syria, onlookers were using my camera viewfinder to try to identify Daesh positions,” recalls Steyerl in her recent book Duty Free Art. “I saw smoke, clouds, houses … among the hundreds of bystanders, few knew what they were actually seeing. I certainly didn’t.” In Steyerl’s words, she was witnessing “shards of images,” fragments of the unending War on Terror’s latest metastasis. Why would one of the world’s foremost contemporary artists be so enthralled with the Islamic State’s siege? The answer likely lies in the fundamentally aesthetic nature of both art and terror.

Recent news that American soldiers will withdraw from Syria offers an opportunity for reflection on the seemingly intractable conflict with IS – as well as contemporary art’s complicated relationship to it. Even if the impending US military exodus unfolds slowly, continued destabilization in the region appears all but certain, and the mark of this episode of the War on Terror on visual culture will be indelible. Looking back, a larger and uneasy relatedness between contemporary art and IS was apparent from the outset, as art media outlets like Hyperallergic and artnet frequently reported on the pseudo-state’s activities as early as 2014. The group’s fascination with iconoclasm and appropriation echoed with similar preoccupations in contemporary art itself, as grainy GIFs, embedded YouTube videos, and screenshots transmitted the demolition of Assyrian statues, Sufi shrines, and architectural monuments. For those who reside outside the Levant, the deepening conflict existed primarily in the realm of the image. Contemporary art and IS lean equally on a contradiction: a yearning for relevant, fresh imagery distinguished from the established order, accomplished only by destroying, recycling, and mutating predecessors’ work. The work of artists like Navine G. Khan-Dhossos, Michael Rakowitz, and Steyerl underscores that much of visual culture, no matter who creates it, thrives off of the destruction of the consecrated.

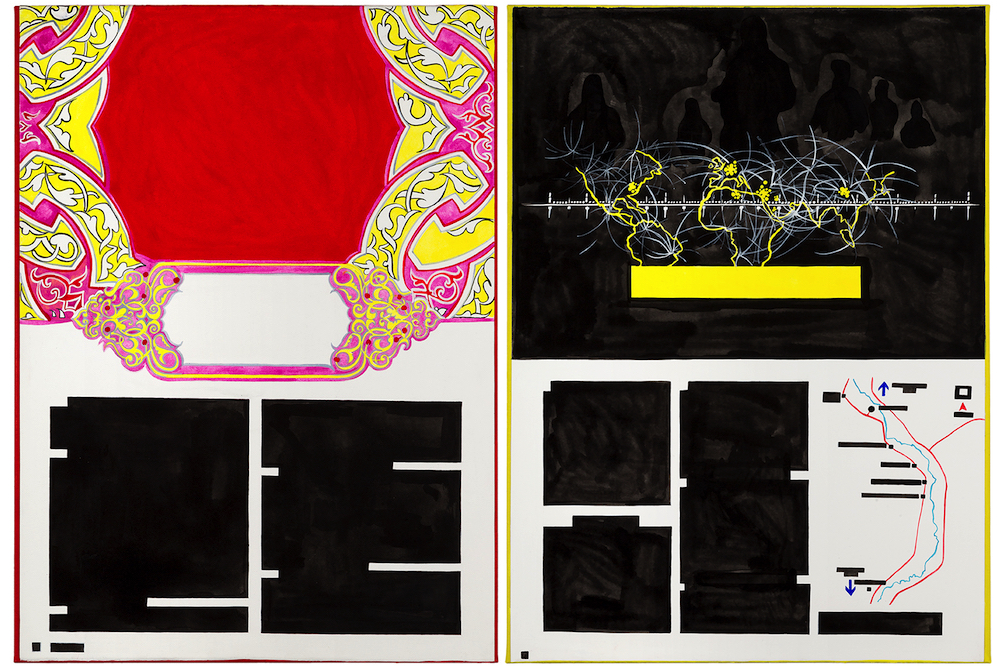

What does the picture of terror look like? It manifests in different forms, produced and shared across platforms we all know well: crafted meticulously with InDesign, saved as a PDF, and shared through WhatsApp. In her 2017 show at Fridman Gallery, Infoesque, Khan-Dhossos debuted a series of gouache paintings that “render” terror. She pulled from the design structures of Dabiq, the Islamic State’s multilingual online magazine, and Rumiyah, its sequel. Limiting herself to CMYK and RGB color palettes, Khan-Dhossos’s fluorescent tessellations and filigree share the canvas with blacked-out bars of text, transforming a didactic page of propaganda into graphic abstraction. Victory to the Patient (2017), for instance, features a floral cartouche pigmented with magenta, red, and yellow, which hovers over two columns of black rectangular polygons. By appropriating the tropes of illuminated medieval Korans, IS’s designs contrive a sense of sincerity and religious authority for their content. By abstracting the text, Khan-Dhossos points toward the banalities of IS’s graphic design; the works tell the story of content-makers who copy and paste from internet searches, recycle images, and tweak vector-files. As experts have noted, image circulation and graphic design are key elements of IS’s propaganda machine, marshalled to complement military campaigns on the ground. As an indicator of the value that IS places on aesthetics, it reportedly compensates media professionals seven times more than foot soldiers. Like all brands, the Islamic State seeks to manufacture a compelling identity. Khan-Dhossos’s art reveals IS’s meticulous emphasis on visuality; their manifestation of terror is very carefully designed.

Iconoclasm translates into virality, an adage that contemporary art and IS both hold dear. At its peak, the group’s imagery was fraught with destruction. Remember the looping videos of men taking sledgehammers to Assyrian statues (or their plaster copies) in the Mosul Museum? Or how the artworld watched with horror as IS exploded the Temple of Bel at Palmyra? These acts of calculated barbarism represent deliberate maneuvers in the networked struggle for control over the realm of the image. Rakowitz’s 2018 iteration of his ongoing project The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, functions as a kind of retort. In it he foregrounds the continuing cultural consequences of American adventurism in Iraq by remaking lost and looted artifacts: a new representation of parallel destruction.

Michael Rakowitz, “The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist,” 2018, on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth. Photo © Gautier DeBlonde, courtesy the Mayor of London’s Office.

Commissioned for Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, Rakowitz fastidiously recreated a lamassu, a winged and human-headed bull hailing from the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh. The original gate guardian referenced by Rakowitz’s sculpture stood watch at Nineveh’s Nergal Gate from 700 B.C.E until recently. In 2015, IS took a pneumatic drill to its carved face, filming and distributing the act of vandalism during the group’s occupation of Mosul. Rakowitz called his version, resurrected with a mosaic surface of green and orange date syrup cans, a “ghost” of the original; it haunts us by virtue of its visibility in public space, and functions as much more than a simple copy. Rakowitz’s spectral language for the project calls to mind a spectrum of perception, in which terror and counter-terror emerge as a contest of visual one-upmanship. What image can endure the longest? What new picture of horror or power or triumph can be seared into media broadcasts around the world? In this case, the lamassu persists despite its destruction: it is elevated into an image of cultural resilience, a testament to the Iraqi people despite centuries of colonialism, as well as a display of “resistance” against IS. The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist underscores how works of art themselves are formidable actors in contemporary geopolitics. Armed with the tools of iconoclasm and appropriation, Rakowitz’s work ripostes the production of terror.

“I think that right now, [the] production, consumption, sale, and even storage of contemporary art is really implicated in a lot of the economies underlying war,” said Steyerl in a 2016 interview. Before IS achieved near-omnipresence in the Western media landscape, the artist created her 2013 film HOW NOT TO BE SEEN: A Fucking Didactic Educational .Mov File, which traces relationships between armed conflict and contemporary art, and anticipates the reasoning behind the artist’s journey to the battle of Kobanê. The film appears as a “how to” video, instructing viewers on various tactics to avoid visibility, a strategy of preservation and privacy against ubiquitous corporate and state surveillance. A resolution target, a device developed by U.S. military in 1960s to measure photographic visibility, stands in front of a green screen and becomes the subject of the film’s various vignettes. “It measures the resolution of the world as a picture,” drones the monotonous narrator in the film’s first lesson. For IS and Western powers that seek to counter terror through adventurist and interventionist means, what is at stake is the very picture of world. Steyerl has fashioned a career through the recycling and remixing of images, revealing how they can be weaponized like shrapnel. And it’s at the level of images where artists like Steyerl can intervene in this struggle, revealing how the sophisticated and tactical production of appearances intertwines contemporary art and IS.

Two decades after its declaration, the War on Terror still feels neverending. Recent reports suggest that while IS has lost significant territory and resources to fuel its propaganda networks, the group will morph and reorganize as a different entity. Such a future will undoubtedly prolong the misery of the Syrian people while functioning as a convenient foil for the Trump administration. For certain, the works of Khan-Dhossos, Rakowitz, and Steyerl help us to see how contemporary art and IS are inherently bound through a shared dependency on images and their making. Even as the American presence in Syria wanes, contemporary art will participate in the feedback loop of terror and counter-terror. Warfare and terror will increasingly hybridize as we approach the middle of the twenty-first century, and images will remain effective geopolitical actors. The work of artists like Steyerl, Khan-Dhossos, and Rakowitz will continue to create and destroy pictures of the world, small terrors in their own right, soft and backlit.

It is so astonishing for me that people can take such a simple idea and turn it into something this creative. I look forward to seeing all her future work as she seems really talented.