Artists have long exploited the Zoroastrian struggle between light and dark to create images. Although darkness implies mystery and melancholy, in the hands of an artist like Rembrandt, it has (in the form of chiaroscuro) portrayed the heights as well as the depths of human emotion. An ambitious exhibition focusing on the film-noir effects of night imagery now argues that a turn to the dark side liberated art from old paradigms, illuminating inner, rather than outer, vision.

Night Vision: Nocturnes in American Art, 1860-1960 at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine surveys a subject that has not been widely explored. Ninety works in diverse media (on view through October 18, 2015) frame the artistic response to electricity’s advent and application in the 1880s, which threatened to overshadow the poetic potential associated with darkness. The curator Joachim Homann believes that, just as electricity transformed the cityscape, American artists used the motif of nighttime to diverse ends, transforming both the craft, process, and style of image-making.

The theory is that literal illumination, which proceeded apace in the East-Coast American cities (and especially in New York) at the end of the nineteenth century, catalyzed artists to forgo their traditional role of illustrating outward reality. Finding new subjects in the shadows where imagination blooms, they exploited metaphorical associations with darkness. Incorporating its themes and low-resolution legibility challenged viewers to expand their idea of what constitutes a work of art. It also forged new directions, as “daylight” views of the objective world yielded to subjective, symbolic image-making.

Another factor that liberated painters from their fealty to realism was the growing popularity of photography after 1850, an aspect of this genre’s emergence that is notably and regrettably absent from the exhibition. As the craze for Daguerreotypes spread, painters were released from the practical role of documenting the physical world. Instead, they could paint the unseen. Both painters and photographers who aspired to join the ranks of fine art seized opportunities presented by technological advances in the nineteenth century, options that eventually led to abstraction.

Organized in a roughly chronological format, each gallery in Homann’s exhibition has a distinct feel, introducing new phases in the theme’s evolution. In a recent interview at Bowdoin, the curator described a “double trajectory” of responses to the altered look of the night. One reaction by early twentieth-century figurative artists in the Ashcan School was to expose new social realities, documenting visible changes in nightlife. Others turned away from the floodlit world, using innovative formal techniques to express internal feeling through a projection onto the shadows. Regardless, the nocturne resurfaces in multi-generational conversations and conversions. Its various developments are so differentiated and staggered that Homann admits, “My colleagues have told me I’ve curated five different shows.”

Staged in a quintet of galleries, the nocturnal theme begins with, first, James McNeill Whistler’s romantic tradition of the nocturne (developed while the expatriate painter lived in Europe) and his successors in the US who were influenced by his work. The next gallery contains high-keyed paintings by social-realist artists who depicted the working-class’s boisterous evening activities, primarily in New York, between 1908 and the beginning of World War I. A gallery of modernist precursors like Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O’Keeffe, who eschewed realism for reductive images preceding abstraction, follows. A revelatory section of the exhibition contains masterful prints that fully exploit the drama of black-and-white contrasts to underline the tensions of urban nightlife. The show concludes with postwar abstractionists like Louise Nevelson, Lee Krasner, and Norman Lewis who exemplify the deluge of Abstract Expressionism that broke on the artworld following World War II.

“The show resonates more deeply with our visitors than any show I’ve curated,” Homann says in a private walk-through. He notes that visitors don’t see this exhibition as merely an art-historical exercise; they align or confront the unfolding narrative with their own experience of the night. “It’s the first time,” Homann reflects, that “people are really starting to cry in the galleries.”

Winslow Homer’s The Fountains at Night, World’s Columbian Exposition (1893) is a particularly affecting work. The dramatic monochrome painting pictures the Chicago world’s fair, termed the “White City” for its dazzling display of lights, its “electric moons.” The largescale, darkling canvas features a silhouetted gondolier thrusting his black craft across a silver lagoon, like a ferryman on the river Styx.

Homer’s cryptic painting – an anomaly compared to his well-known marine scenes that glorify the power of nature – is among several key works in Bowdoin’s collection that inspired the exhibition. One of the oldest college art museums in North America, the Bowdoin Museum is particularly strong in American art, with more than 20,000 items acquired since its founding in 1811. Several standouts share a night setting, like John Sloan’s oil painting, The Cot (1907), which features a blowsy woman preparing for bed; Edward Steichen’s famously fuzzy photogravure Moonlight: The Pond (1906); and an enigmatic Andrew Wyeth painting, Night Hauling (1944), which upends all expectations about that archetypal realist painter’s hyper-clear images. These works bookend the exhibition’s varied poles.

With each gallery’s unique focus on a particular aesthetic or generation of nocturne painting, contradictions abound. For example, the blunt, down-to-earth portrayals of the energetic side of the metropolis’s evening spectacles by early twentieth-century painter George Bellows – known for his dynamic scenes of boxing matches – stand in sharp contrast to the muted, Biblical images rendered in subtly harmonious tones by Henry Ossawa Tanner. The diversity of curatorial and canonical approaches onto the genre consistently unseat expectations.

Another virtue of the installation is that Night Vision is broadly inclusive. Homann has pointedly infused the canon with alternative, often marginalized, protagonists who figure prominently in this genre’s narrative arc. There are works by less well-known women (like Marguerite Zorach, with her decorative Cubist paintings), African-American artists (Beauford Delaney’s imaging of a jazz club, jolting with rhythm), and artists who felt alienated in unfamiliar territory like the Italian-American Joseph Stella, who immigrated to the United States in 1913. His ominous rendering of Factories at Night – New Jersey (1929), in which a cylindrical storage tank almost blots out the night sky, suggests the dehumanizing power of industry, vastly divergent from his signature motif of the Brooklyn Bridge, where his Futurist-inspired canvases celebrate technological might.

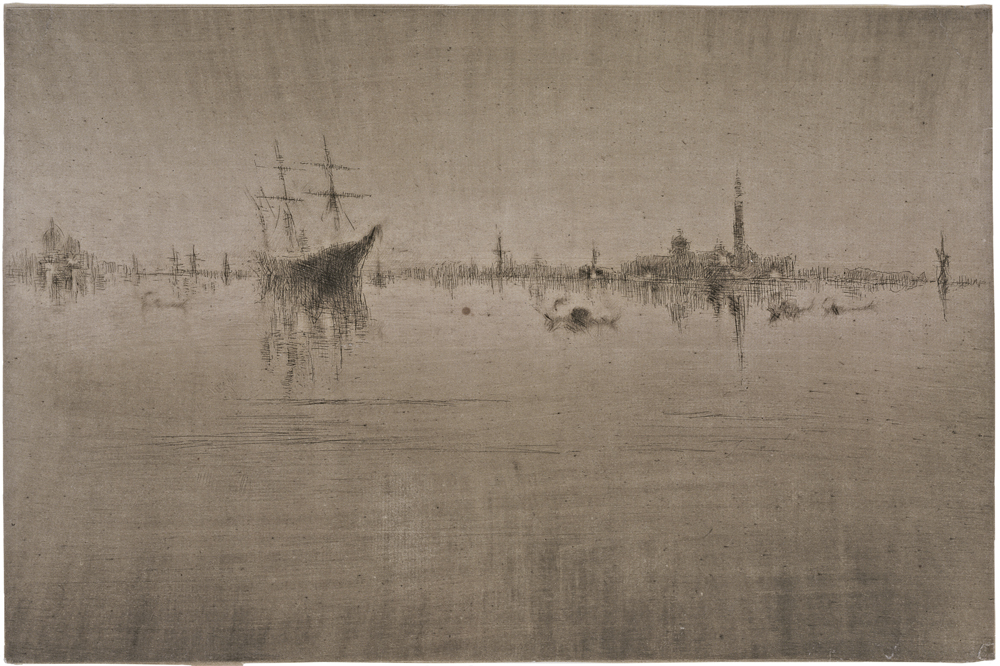

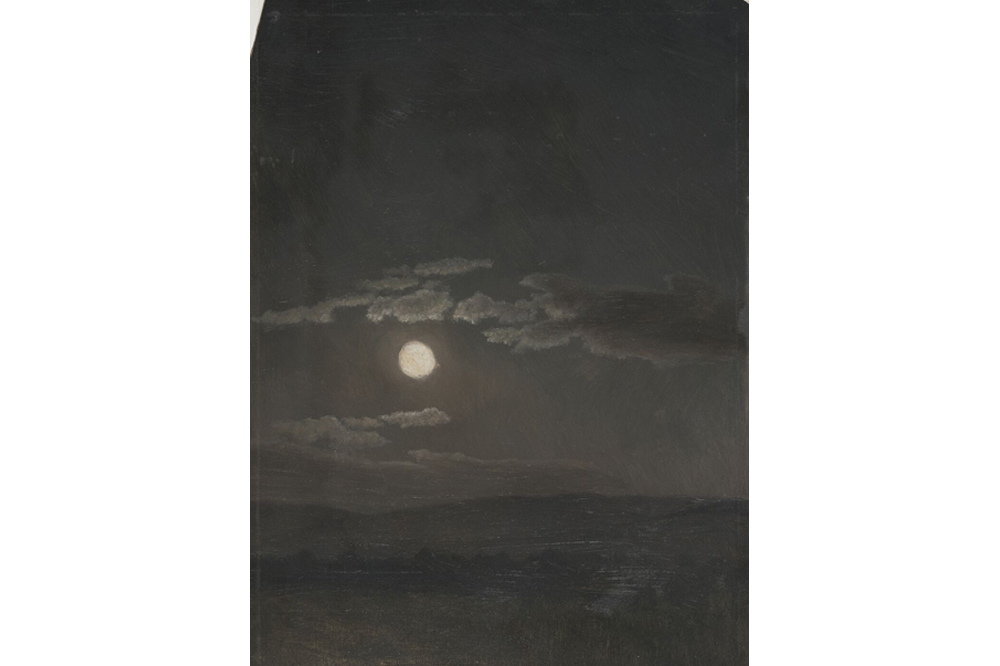

However, any show of nocturnes must begin with Whistler, who popularized the genre in the 1870s with his obscure night scenes featuring the River Thames in London and Venetian canals. At that time, gas lamps produced only weak, local light near their source; darkness still dominated cities at night. Whistler enveloped his landscapes in a misty atmosphere to disguise ugly, industrial infrastructures, cloaking, he said, “the riverside with poetry, as with a veil.” In his etching Nocturne, from The First Venice Set (1879-80), indistinct boats and buildings seem to dissolve into delicate lines that fade out, an effect achieved by wiping ink from the copper plate.

In the same initial gallery, others opt to conceal more than reveal, emphasizing the picturesque over the real. Photographers in the Pictorialism school seeking to establish their medium as a fine art (as distinct from “button-pushers” with newly popular Kodak cameras) undertook night scenes as a technical and aesthetic challenge. Edward Steichen manipulated his view of The Flatiron (1904) by brushing pigment on the negative to give it a blue-green tonality and shrouded the skyscraper, an emblem of modernity, in a diffuse, painterly mist. Similarly, the American Impressionist Childe Hassam’s Nocturne, Railroad Crossing, Chicago (1893) pays homage to Whistler with its atmospheric portrayal of reflected streaks of light on a rainy street, obfuscating the view of undistinguished buildings by transforming the mundane into the mysterious.

After public spaces were electrified in New York in the 1880s and ‘90s, Ashcan artists (who portrayed working-class, often seamy scenes) reveled in the vitality of a nightlife newly visible. A gallery containing works by William Glackens, Everett Shinn, Bellows, and Sloan amps up the wattage. Their works virtually crackle with electricity and excitement, in contrast to the calm, restful tenor of the preceding gallery featuring softened, atmospheric sketches.

John Sloan not only painted streets packed with raucous crowds, he peeked into his neighbors’ private abodes. Three A.M. (1909) pictures two women in nightclothes, one likely a “woman of the night” who’s just returned home. Edward Hopper’s Night Wind (1921) is another realism-cum-voyeurism portrayal of an unguarded, intimate moment, featuring a naked woman crouched on a bed by her window.

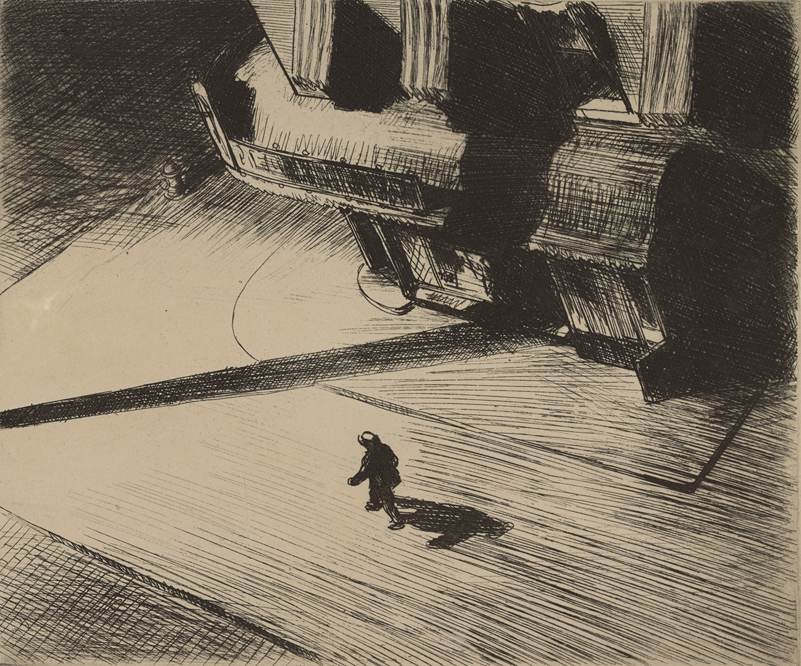

A gallery devoted to black-and-white prints highlights a quintessential Edward Hopper, an etching titled Night Shadows (1921). Seen from a distant, overhead perspective, a solitary man stalks towards a raking, diagonal shadow that climbs up a darkened building like a plume of smoke. A tour-de-force evocation packed with emotional intensity, the scene projects foreboding through its sharply angled perspective, ominous shadows, and jagged, scribbled cross-hatching.

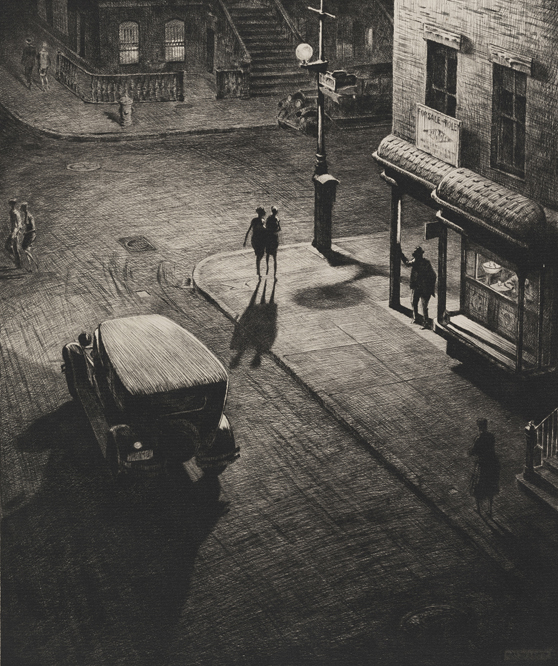

Among the exhibition’s major discoveries is the work of Martin Lewis, a late-nineteenth-century Australian artist who emigrated to the US in 1900, here represented by dry-point prints that portray the city at night. We get a sense of a new class of urban workers, returning home after nightfall. Lewis’s mastery of light and shadow employs more tonal range and varied lines than used by his friend Hopper. Relics (1928) portrays an urban scene very similar to Hopper’s (both from an aerial perspective), but the mood is peaceful and safe. Instead of a lone walker, three couples stroll arm-in-arm. Shadows are short and fused, non-threatening.

The exhibition makes the point that artists who were considered visionary, or as outsiders, like the mentally disturbed, largely self-taught Albert Pinkham Ryder and Albert Blakelock, turned to night scenes as an ideal locale for their symbolic images of inner torment. The fact that darkness obscures detail liberated such artists from the need to represent reality, which freed their imaginations to portray symbols loaded with psychological anguish. Ryder’s Macbeth and the Witches oil painting (dated to the mid-to-late 1890s), has a heavily impastoed surface so cracked and blackened as to be almost indecipherable. It conveys a sense of the obsessive undercurrents gripping its author, a reclusive New Englander with Spiritualist leanings.

The mystical pantheist Charles Burchfield also painted haunted nocturnal scenes that seethe with emotion. The Night Wind (1918) is one of the most idiosyncratic works featured. This watercolor is fraught with menace, a spooky, anthropomorphic house with yellow windows like chilling eyes.

The physical fact of darkness that characterizes nocturnal images partially explains why this exhibition marks one of the first major surveys of American art dealing with night scenes. (Cincinnati’s Taft Museum presented a smaller exhibition in 1985 of 27 American artists who painted nocturnes in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.) Homann explained that the museum’s public relations staff and publisher of the catalogue were anxious that the show not appear too dark (literally) and gloomy (figuratively).

As evidence of the exhibition’s argument that night subjects led to stylistic innovations and ultimately to abstraction, it concludes with a few cherry-picked, mid-century modernist canvases. Norman Lewis’s Reflected Moon (c.1954) an image of a shadowy orb overlaid with spiky, barbed-wire-like lines of blurred blue and umber, may have had personal resonance for the African-American painter who felt marginalized by his race.

Perhaps the relative invisibility afforded by dim light permitted a measure of anonymity and freedom for artists outside the mainstream tradition (women, African–Americans, and outsider artists like Joseph Cornell). Lee Krasner, one of the few women among the first generation of male-dominated Abstract Expressionists, created paintings in her 1959-62 series titled Night Journeys. One of those, Assault on the Solar Plexus (1961), is an abstraction comprised of aggressive, gestural brown circles applied on a sepia background. Krasner’s image doesn’t promote an obvious lunar reference but the catalogue conjectures that it was the result of her wrestling with subconscious anxieties during her night’s work.

The curator’s selections and chronological installation make a case that the advent of electricity influenced a successive, reactive trend away from representational imagery. What’s beyond the scope of such a tight focus is whether the modernist and abstract artists who abstained from night imagery were also influenced by the social and aesthetic changes introduced by electric lighting in the 1880s. Dedicated to exploring the legacy of the nocturne, the catalogue downplays other factors that accelerated the trend like photography, as well as the spreading influence of proto-abstract technique by Impressionists like Claude Monet or the post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne.

However, the subject unites an eclectic group of works demonstrating Whistler’s conviction that less can be more. Whether the influence of the nocturne caused a shift in style, the act of filtering reality through the scrim of vision fosters invention and originality. For the artists included here, the nocturne-as-motif appears to have loosened them up to fill the void of the unseen, permitting fears or fantasies to assume the form of art. Night Vision helps us see the light in the dark.