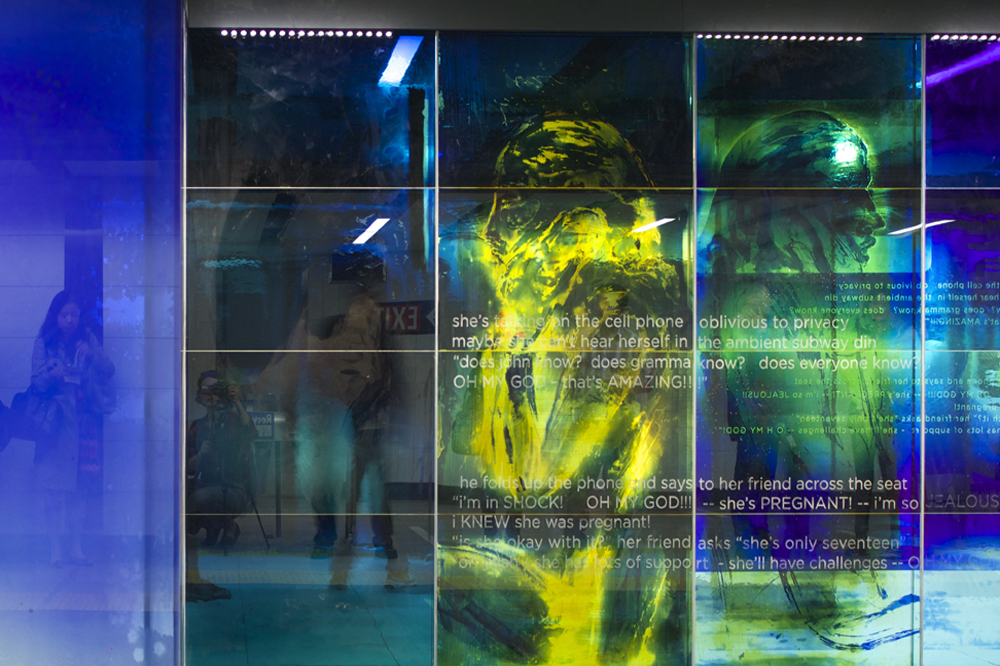

Toronto recently saw Union Station’s protracted and over-budget revitalization project achieve one of its first clear signs of completion, an expansive public art installation that runs the length of its subway platform and features a cinematic reel of stained-glass panels sketched with commuters and clips of poetic text. Produced by Toronto-based glass artist and architect Stuart Reid – who won the commission through an international competition and spent eight years on its realization, across Canada and Germany – the complex two-track glass partition required sophistication in its making and a certain legibility for its public. The result is a scroll of Reid’s sketched impressions from riding the subway cars, loose portraits of passerby as they move between metro stations and life obligations, pensive, distracted, anxious, tired, engaged. It’s public art in the tradition of real-time observational drawing, even as it maintains the bleeding palette, gestural line, and sweeping scale of Reid’s oeuvre (which includes the Salzburg Congress, Toronto’s St. James Church, and Living Art Centre, among others). But unlike Honoré Daumier, a mid-nineteenth-century caricaturist who reflected the French people back to themselves, achieving the role of acute social commentator; or, say, Michael Snow, whose mawkish Skydome sculptures convey a balloon-cheeked jeer, Reid has attempted something like realism with a shaky, handheld mirror. And as such, he’s produced a work of public art that’s dangerously sincere.

Realism and sincerity invite critique. It comes as no surprise, then, that the Toronto Star – which somehow manages both an alarmist and dismissive discourse – responded to Reid’s Union Station project with the leading question, “Is the new public art at Union Station depressing?” The article detailed the “man-on-the-street” response, with people communicating their tax-payer’s disappointment. A second article followed, this time from the Star’s critic Murray Whyte, who claimed he wasn’t “ready to give up” on Reid’s zones of immersion, despite comparing its unfinished project to a team’s outcome two-thirds of the way through a losing season.

What neither article made clear was that Reid’s commission wasn’t washed, lit, or fully installed at the time of their publication. “I don’t know who thought that was a good idea,” reflected one of the respondents to the question about the installation’s tone. I wonder the same about the Star’s ill-conceived coverage.

So I sat down with Reid to gain insight into the media’s initial response, and what it evidenced about our current societal distrust of public art. Further, it was an opportunity to discuss the larger questions that dog our generation’s relationship to public art: what is public art? How is it failing us? Where does it succeed? What is its responsibility to our public? Reid was impassioned and searching in his reflections.

You’re an internationally-exhibited glass artist and architect, producing large-scale commissions for public sites since the early 1970s. What’s changed in public art and its reception in the time that you’ve been doing it?

It’s changed for me because a lot of what I started doing – commissioned work, where you’d have somebody who’d want something, and you’d have to slip the art in – meant it was always a case of “how do we make a go of this?” Like I did a piece for the Living Art Centre, and they wanted a donor recognition [in the work]. I remember Robert Rauschenberg talking about the dollar bill in one of his paintings and he asks, “is it a portrait of George Washington, is it a portrait of American imperialism, or is it a piece of slightly dirty grey-green? If I treat it like than I can put anything in there.” And I thought, that’s how I could treat the donor recognition and still have this wild work of art. But I’ve moved away from doing that. I don’t want to make any movement towards what somebody else’s agenda is. So the agenda of this work of art, which is very different, is that it is a work of art in Union Station. There are technical things that are very exacting but, then, every work that’s site-specific has that. Here, they weren’t asking for anything – the history of Toronto’s mayors, or lots of children playing in daisies – they didn’t have any agenda, and that’s what made this quite interesting.

On the other hand, when you’re working in the public realm you’re always working site-specifically, and this is a very powerful site. And I kind of think when you’re working with a site, and the architecture, the context, all the agendas of all the players, you’re either kind of using those things to run with the project or they’re going to trample you to death. I thought about that. It was an international competition, and I needed a clear idea to win it. And I wasn’t interested in something that’s fictive. It has to be about the experience of being here, about the experience of dwelling here.

I went and rode the rails and did drawings and just dwelt in it for a long time.

I’m curious about your choice to be figurative with this piece, and to use text, both decisions being a risk. With the first, you’re really depicting your subject back to your subject; and with the second, you’re being directive about meaning. Where these decisions difficult to arrive at? Did you worry about these things being limiting in terms of its reception?

Yeah, they were both difficult. But I thought the thing to do was to be like one was physically walking through a movie. As you’d move …. you’re never going to see the whole thing, it’s way too long. Even if you walk forwards and backwards, another train will come. So it had to be something you could see close-up. A slice of a huge, perspectival thing. It would have been easier to do this in colors or with bands but I wanted something that was personal, and vulnerable, and had the possibility of real failure. One of the things I really dislike about public art is how sanitized it is. It protects itself from failure. Such that one of the words associated with public art is bad – bad public art.

Well, the idea of doing something figurative that’s 500 feet long is almost certain failure. How could it not become tedious, tired, the whole damn thing wandering forever? How could writing something not be incredibly dull? How would it not bore people?

We all are site-specific, we all come from a family or an ethnicity or a gender. [But] we’re all – the consciousness of people, more or less, is something you can tap into by being human. It’s almost as if the [subway riders’] characteristics didn’t matter. When I was sketching them, I just got a glimpse; I’d glance up for half a second, and I got a feeling that theirs wasn’t all that different from my life, that you weren’t all that different from them. There’s this whole issue of the self and the other, the individual. But no one’s on a joyride on the subway. They get up, they go to work, they come home, and they’re beat.

Is that too dour an interpretation?

It’s not the only interpretation but you’d be foolish not to see it.

I don’t know. Your take on it makes me think of Daumier or something, a dark, soot-stained portrayal of what I don’t think everyone agrees is a joyless experience.

It’s not all joyless and sometimes you get in there and it’s cool, you’re going to the game, maybe; but there is this sense that there’s a basic pulse in the city that you go to work and you come home – that we’re longing to get home again. I don’t think that’s dour, it’s just part of what’s going on. People are, in that reality, reading a book or checking their emails. Advertising has us thinking that we’re meant to be on a beach in the Bahamas, or reading some great epic novel, or madly in love. But a lot of our lives are spent in this transition zone between one necessity and another.

How important is it for public art to reflect our experience back to us, or, alternatively, to elevate our experience, somehow; to make our environment a more enjoyable place?

I think it’s both. I think you don’t want to make the space something that’s a drag to be in. You’re in a tube. How to do you make that reflective? And how do you make people reflective of the space that they’re in? This is a very public space and they’re pushed into necessity. How do you break that to make it a reflective experience? I think all art has to have that capacity to have a reflective experience. Or a deeply beautiful experience. The dance of energy and matter.

I’m focused on the idea of service to the public, curious to know why public art gets such a bad rap, in your opinion.

We are told all the time that we’re great; we have this view that we’re greatly entitled. And yet our lives are less entitled than the promises made. So art has to reflect the life and the possibility. It has to do both or it doesn’t work. If people think that the psyche expressed in art is of no value because they might not always like what they see, and they don’t want to pay for it … Some cultures harbor a resentment for the public having a purse. And some cultures think they value public art, and great works of architecture; they spend money on it and reap the rewards. Canada doesn’t have a long history of valuing public art, but I think that’s beginning to shift.

There’s always the possibility to meet people where they’re at. But you can set the bar a little differently and they will come to where you’re at. You know people didn’t like the Henry Moore when it first came to Toronto [The Archer, installed in Nathan Phillips Square in 1966]? There was a huge fuss about that; it’s unimaginable now! Now, Nathan Phillips without the Henry Moore would be utterly depleted.

People don’t mind spending money on sports because they value sports. They get more money than we do, more of the public purse. And the great benefit of having this parade of physical excellence gets understood by most people.

Sport is legible. There are rules and jerseys with certain colors on them, and you learn it, and then you have favorites, and a beer with your friends, and it’s rallying. Whereas in contemporary art, there’s a census that it hasn’t been legible in a very long time. So you chose to be figurative, as we noted; how consciously were you trying to educate – to bring along, and bring up your public?

I knew that space would be a tricky space to engage people in a one-to-one experience; the advertising, the trains, the push-and-shove was going to be aggressive, and then you’re also very close to it. So I also knew that figuration is what the human psyche can attach itself to. There were a lot of reasons why doing something figurative was dangerous, but I knew it would capture people’s attention rather than not be seen, or be considered of no consequence. I don’t think all public art should be figurative, for crying out loud. But when you do it, people say, “aha,” I recognize that, and the conversation starts to be engaged.

There’s a scene in Amadeus, where Mozart walks to the fountain and walks back, every morning, the concerto in his brain. Louis Kahn said people should be able to feel their future. You don’t do that by making nebulous, psyche-less space. Public art, when it’s strong and powerful and engaging and pushing the limits of what’s acceptable, does that. After a while, what was pushing the limits of what’s acceptable, the public always understands that a little later. Nobody worries, by the way, about what was spent three years ago.

What surprised me was that the number circulated in the Star was so little ($160,000), but they made it sound like so much.

The amount was how much I was paid over an eight-year period for doing my part. The budget between the installer and the TTC was separate. When the fabricator firm I was working with went bankrupt and I wanted to protect my things, I had to buy them. There were lots of costs like that. But whatever amount it is, it’s a drop in the bucket in terms of what we had to do.

The idea that you could walk around and in the public realm see things that mark space and say that this is a city of ideas and has some soulfulness and some vision of where we’re going. The art part of it isn’t just the decorative icing on the cake. Public art if it’s any good has to be art first and public second.

How much do you care about your public’s reception?

I work like crazy to do something for the people of Toronto – something that would give them psyche and aliveness and coolness and the sense that they are valued. And I want them to really love it. … When they will, I don’t know! [laughs] I’m sure it’s coming soon.

I thought the Star articles were very unfortunate. They looked at the piece when it was unwashed, unfinished, and unlit. And did a judgment on about a third of what was up. To throw something out in a free newspaper that says, “we’re holding a survey on whether this is beautiful or depressing,” when it’s unwashed, unfinished, and unlit, was unfair. It made a big stir and I think it poisoned the well. But sooner or later people will understand.

How do we elevate the discourse on public art?

Well, we have a discourse. Just by having one means we’re elevating it. Maybe people being told that this is depressing, and then going there and realizing, “no it really isn’t,” and then the next time they read something they maybe say, “oh, I think I’ll decide for myself” – maybe that’s progress. Because while it’s unfortunate that the opening salvos were so ill-considered, the city will sort this out. I think public art either gets better or worse with age. I think in five years a lot of people will have taken pleasure in this. What is it to be human? What is it to be here? There was nothing like this before I started it. There has never been a work of art this long, this strange, this personal, or this vulnerable in the public history of this city. So now it’s out there. And it’ll grow on people, I have no doubt.

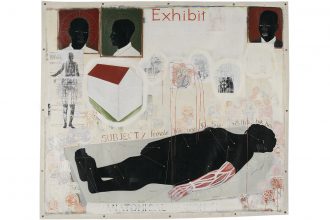

Interesting read, though perhaps the headline is misleading—it sounds like a vindication, but the work in question actually puts far too much emphasis on “public” and not nearly enough on “art”. That is, the project seems to take as its mandate the reflection _of_ a public back _to_ that public (in the form of transit riders looking at mannerist drawings of transit riders), with little to no importance placed on metaphor or nuanced ideation.

Indeed, such a superficial and slapdash looping is public to a cartoonish, even exploitative, degree, and I suspect grows from the same misguided, two-pronged impulse that makes news organizations want to superimpose viewers’ live Tweets over every broadcast: a simultaneous abdication of authorial responsibility and adoption of an ultimately self-serving rhetoric of community engagement. Reid’s project takes the public by the collar and says, “see? This is you! Here’s you are! Don’t you feel represented, now!?”… which is at best a redundant, pointless acknowledgement, or at worst perfectly poised to inflict a self-conscious horror. After all, when confronted with one’s own ugliness, made even uglier by an artist’s gestural filtering, the obvious and understandable response is to recoil.

I agree with Lee