It’s unfortunate, but not surprising, that critical attention and institutional acceptance usually arrives too late to the work of women artists and artists of color. Often this recognition intensifies alongside the illness and/or impending death of the artist: just late enough to serve as a reminder that their voice is welcomed only once it can no longer actively object.

This tired narrative found form in The Brooklyn Museum’s comprehensive exhibition of the painter, sculptor, photographer, earth artist, and documentarian Beverly Buchanan. The exhibition, Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals, opened at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the fall of 2016 – just a year after the artist’s death. Organized by guest curators Jennifer Burris and Park McArthur, it committed to creating a space for the artist by foregrounding Buchanan’s significance to a bevy of art-historical discourses, including land art, post-Minimalism, feminism, and “outsider” art. While the curators’ reconstruction of Buchanan’s career was a worthy and urgent project in itself, the museum’s permanent installation of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974-79) – an iconic work in the history of feminist art – ceded little ground. Its large triangular exhibition space at the center of the institution forces all visiting exhibitions to the margins, a choice we might read as privileging a white, middle-class feminism. At very least, snaking around the collection of outlying galleries too small and irregular to properly animate Buchanan’s work served as a bitter reminder of how women artists of color and Black feminism can be cast parenthetically in institutional presentations of art history.

On the other hand, the exhibition’s second presentation at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta, Georgia – a historically Black teaching and collecting institution dedicated to the promotion of women artists from the African diaspora – presses back against the museological and critical maneuvers that render marginalized artists more marginalized. The welcoming exhibition plan and brightly-colored walls of the Spelman Museum’s layout made for a poignant counter-gesture to the Sackler’s design limits and white-cube aesthetics, and allowed for more freedom and space to holistically assess the great range and scale of Buchanan’s work. Comprised of over 150 objects (many culled from local private collectors and Georgia-based art institutions), including large-scale paintings, cast concrete floor works, shack sculptures, and archival projects; as well as a rich selection of photographs, sketchbooks, notes, and ephemera from Buchanan’s personal archive, Rituals and Ruins at Spelman moved beyond the teleological model that so often regulates monographic exhibitions to unearth the powerful relationships between Buchanan’s artistic practice and her Southern origins. More importantly, Spelman’s presentation placed the artist’s commitment to issues of racial injustice and historical commemoration at the center of her oeuvre. The result is a triumphant homecoming for this prolific artist with deep ties to the rural terrains, architectures, and artistic communities of Georgia (Buchanan grew up in South Carolina, and lived in Macon, GA later in her career), in an institution committed to the exhibition of women artists of color.

Jerry Siegel, “Beverly Buchanan, Athens, Ga, 2000,” 2000. Image courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Contemporary Art Georgia.

Buchanan’s investment in site-specificity was cultivated as a child, during visits to rural tenant farms across the American Southeast with her adoptive father, who at that time was Dean of the School of Agriculture at South Carolina State University. Her penchant for academic study and research was mobilized toward a rigorous education in medical technology and public health, before she turned to art full-time in 1971. She enrolled in painting classes with Norman Lewis at the Art Students’ League in New York. Several masterful examples of Buchanan’s early paintings appear in this exhibition, specifically, Brick Church Wall (from the Torn Walls series) (1975), which forms a centerpiece in the main gallery, and acknowledges not only the significance of the medium and abstraction to her work, but the influence and mentorship of Black painters so crucial to her early confidence and success, namely Lewis and Romare Bearden. More importantly, the continual appearance of Buchanan’s bright, energetic paintings of homes, landscapes, flora, and fauna overwhelmed by thickly layered scratching of pure color, reveals her exposure to Abstract Expressionism via Lewis, and a deep reverence for the Black Arts Movements of the 1930s and ‘40s. This presents an important revision to contemporary narratives of Buchanan’s work. While other institutions often push her painting to the side in favor of her more conceptual, interventionist gestures and three-dimensional practices (implicitly aligning her with histories of white, male-dominated traditions such as Minimalism and Land Art), the Spelman Museum points to the artist’s deep ties to a history of Black painting in the United States, and the social- and racial-consciousness that grounds her artistic lineage.

The decaying and abandoned buildings of New York and New Jersey that Buchanan explored during a brief stint as a health educator in the late 1970s inspired a shift in form. What emerged were her “frustulas,” a series of pigmented concrete sculptures cast in milk cartons and bricks, arranged in stacks or clusters on the floor. Archival black-and-white photographs capture Buchanan alongside her cast fragments, placing her in relation to the totem-stacked configurations, and emphasizing the bodily demands of sculpture and encouraging exploration of the space around the frustulas in the gallery. Beginning with small studies on her kitchen table and gradually increasing in size and scale, Buchanan thoughtfully and quietly placed the works into the urban industrialized areas of the North. Later, after her move to Macon in 1977, she brought them to a rural Southern landscape as a way to mark or memorialize sites connected to the fight for racial equality at a local level. These “deposits” of stones in unmarked slave graveyards, businesses with recently-dissolved racist hiring procedures, or public spaces named after racist cultural figures, point to ways that history is buried, or at times blatantly ignored. The frustulas thus suggest a solution for recovering and honoring the voices of those rendered silent.

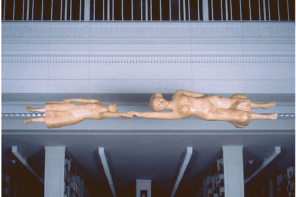

Beverly Buchanan, “Three Families (A Memorial Place With Scars),” 1989. Image courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art, David Henry Jacobs, Jr., and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art.

Buchanan’s most recognizable works, her playful “shacks,” are dispersed evenly across Spelman’s galleries. Upon first glance, the small sculptures seem simple and unsophisticated, until further inspection reveals the diversity of Buchanan’s materials and the intricacy of their arrangement. Striking juxtapositions of surface textures, architectural angles, and material contrasts underscore the sparse inventiveness of their referents: similar structures Buchanan encountered on her long drives across the backroads of rural Georgia, or recalled from childhood memories of site-visits to run-down sharecropper dwellings across the Southeast. Often accompanied by “legends,” or short quasi-fictional texts about the original shacks’ inhabitants, Buchanan’s works invite us to acknowledge the resourcefulness and creativity of the disenfranchised: those who built homes, however precarious, in spite of violent, systematic racial oppression. Three Families (A Memorial Place With Scars) (1989) collapses the matter, memory, and historical trauma bound up in the sculptural project: photographs from her archives reveal her decision to let a friend light the shacks on fire. Their burnt surfaces form a stark reminder of the racial violence towards the Black community in the era of Jim Crow, and the indelible imprints this left on our collective imaginary.

Spelman’s attendance to the fullness of Buchanan’s artistic output and her relationship to the politics and histories of the region, forces a reevaluation of her career as an “outsider” in all respects. It especially challenges the condescending and deeply racialized legacy of categorizing artists of color as naïve and unskilled (meaning uneducated): of positioning them inherently “outside” vetted cultural forms and contemporary art practices, and thus as irrelevant and uncritical. Her advanced training and proximity to discourses and leaders central to the production of painting, sculpture, and Black and feminist art in the 1970s and ‘80s renders her a crucial contributor to those lineages. Buchanan’s work is thus not that of an “outsider” looking in, but a densely connected, nuanced set of informed strategies that foreground the complexities at work in the simplest of gestures and objects. Her deep investigations of rural Southern life pose timely, urgent questions about whether – and how – adequate memorialization of racial violence and injustice is possible. Hidden in plain sight, Buchanan’s subtle, site-specific ruins, ephemeral actions, and modestly-made shacks make memory concrete, and chart the artist’s evolving engagement with the struggle for visibility as an artist, woman, and African-American living and working in the South.

2 Comments