In 1990, Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz was a wasteland. German partition had sent the square back in time, making space for “The City of the Future.” But, like much new architecture in post-reunification Berlin, the structures that rose out of that void are ridden with the anxiety of being: terrified of giving form to a newness that might change everything again. The Besheim Center is built in the style of Chicago’s early high-rises, its light-stone façade claiming Modernist objectivity, while the crescent glass fronts of the Sony Center and the Deutsche Bahn tower look like Frankfurt or London or anywhere, almost. Modernism, here, functions not as a site of experimentation, but as the safe standard, signaling business as usual.

A stone’s throw from Potsdamer Platz, inside the Martin-Gropius-Bau, an exhibition series exhorts us to “rediscover the modern.” The first entry, Frederick Kiesler: Artist, Architect, Visionary, offers the first comprehensive show dedicated to the multi-disciplinary avant-gardist in Germany. This retrospective manages to serve as a reminder of something broadly intrinsic to modernity: a fragile sensibility oscillating between breathless innovation and sharp disappointment.

The show introduces Kiesler through his early designs for exhibitions and theater sets in Berlin and his native Austria. Like a Malevich painting turned three-dimensional, or a Rietveld chair exploded into a levitating shelving system, Kiesler’s display units from a 1924 exposition in Vienna brilliantly illustrate his influences as well as his dedication to the gesamtkunstwerk. Adamant not to distinguish between the arts, Kiesler programmatically turned all engagements with culture, whether theater or visual art, into total experiences.

What a strange, hollow feeling, then, to encounter these projects only as flyers in neat vitrines, or photographs in tidy black frames. A couple of the colorful wooden units have been reproduced but leave almost all of their contextual impact to be imagined: far from the complete immersion Kiesler intended. The truly experimental design for Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century exhibition (1942) – paintings hovering off rounded walls at different angles, sculptures perched on arched chairs – is exhibited as a scaled model.

Peggy Guggenheim’s “Art of This Century,” New York 1942. Photo: Berenice Abbott. © Getty Images / Friedrich Kiesler Stiftung.

The unsatisfying representation of Kiesler’s work represents a compromise: the practical solution to the problem that none of these structures exist anymore (and, in most cases, never did). It also stages a philosophical problem at the core of the Modernist avant-garde: the materialization of radical ideas necessarily undercuts their definitional emphasis on newness, as objects find their place in institutional history. Samuel Beckett once said of Finnegan’s Wake that not only is it not written in English, “it is not written at all.” While this ontological ambiguity lends itself to fine art and literature, it leaves architectural Modernism’s wider ambition to collapse the art-life distinction in something of a stalemate.

When Kiesler planted his feet in New York in 1926, Friedrich became Frederick and his designs went from impossible paradox to compromised materiality. His De Stijl compositions were transposed onto the façade of The Film Guild Cinema and his Constructivist influence underscored window displays at the Saks 5th Avenue department store. Kiesler’s aesthetic shift from hard geometric lines to a biomorphic vocabulary is neatly contained in the model for the Space House from 1933, a private residence, which, in spite of its relative conventionality, was never built.

The exhibition texts are quick to celebrate works “as innovative as they are revolutionary,” but with little context, it’s difficult to decipher whether this formal “revolution” accompanied a particular socio-political strategy. More theorist than architect, Kiesler developed a sharp critique of European Modernism with his concept of Correalism: a recognition that natural, human, and technological environments interact continuously, on an equal plane. Sprouting from this concept over a period of several years (first presented in 1950), the amorphous Endless House is a single, unbroken cast-concrete surface based on the infinity sign, which arcs into any number of pod-shaped enclosures.

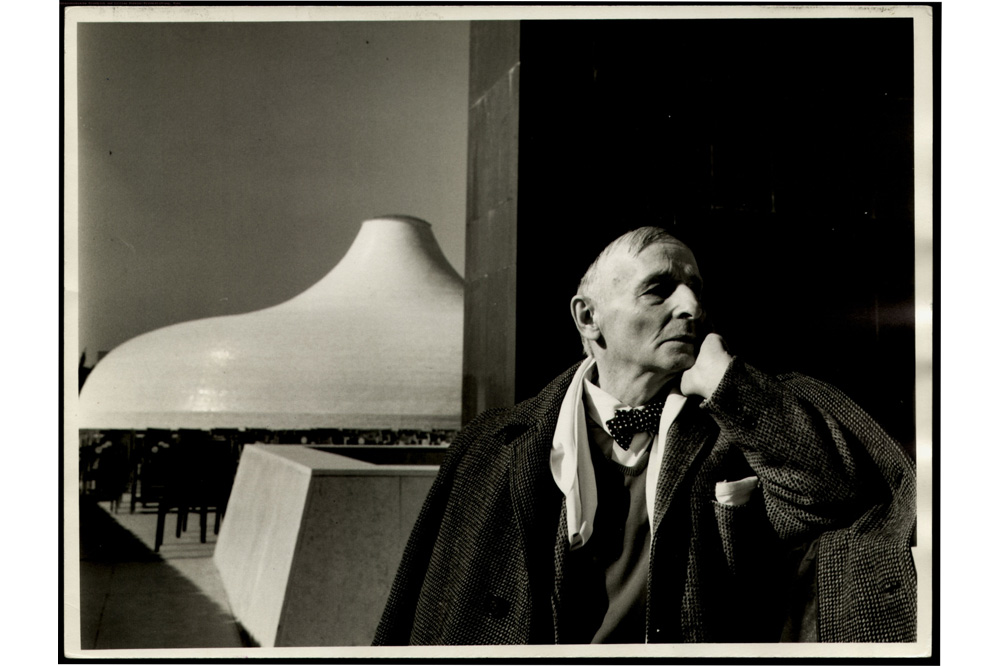

Friedrich Kiesler, “Endless House,” New York, 1959. Photo: Irving Penn. © The Irving Penn Foundation, Condé Nast Publications, Inc.

Like the reproducible housing templates that came out of the Bauhaus school in Europe, the Endless House was conceived as a new way of living. But contrary to those attempts, as evident in his design for Art of this Century, Kiesler wished to free both people and artworks from the confines of the white cube. In one surprisingly ambitious TV interview (on view in the current exhibition), Kiesler explains how the house can be at once universal and individual: magical, even. But like the earlier use of the word “revolutionary,” the key terms here name an aesthetic hypothesis rather than a social theory. So the question remains whether the Endless House is more anti-bourgeois subversion, or proto-neoliberal dream of incessant flexibility and expansion.

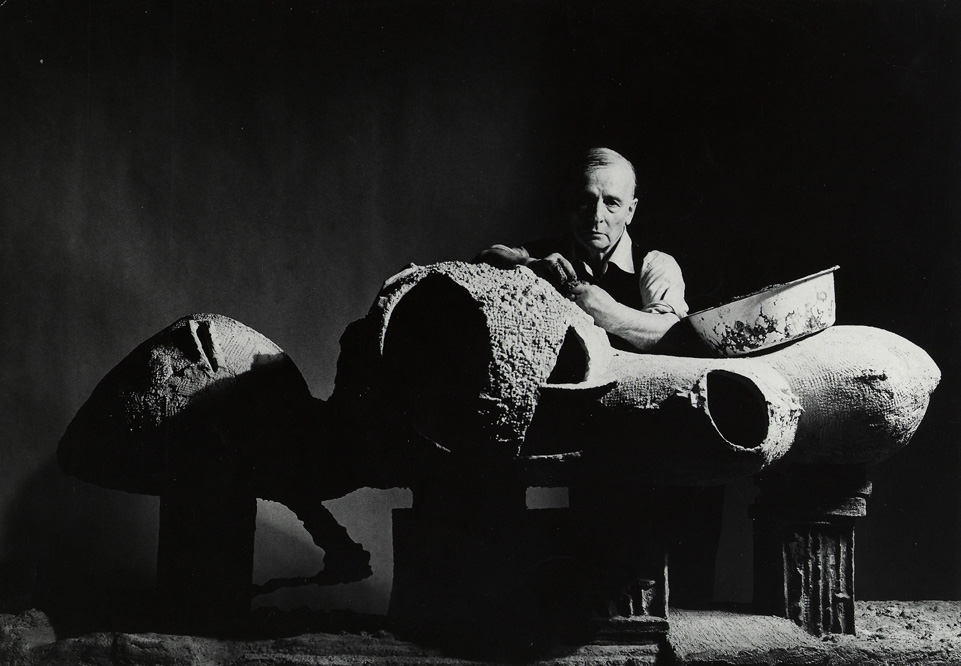

The answer, of course, given Kiesler’s non-distinction between art and architecture, is neither. In 1952 he produced a series of sculpture-paintings contrived as living spaces. In light of the Galaxies – as they were called – the visually similar papier-mâché blob of the Endless House seems a tortured spirit held in painful suspension between vision and material reality. A photograph of Kiesler nesting inside a galaxy is an intimate portrait of what had become of his dream of the gesamtkunstwerk: artist and artwork, one taking shelter in the other, with scant reference to the outside.

Kiesler’s concepts of the endless and universal provide elaborate and elusive ideas in which to hide – something like spiritual sanctuaries. And in the end, his only built structure is exactly that: a shrine for the Dead Sea Scrolls in Jerusalem, completed the same year he died, 1965.

Fifty years on, Kiesler’s ethos of innovation endures. Or so a dedicated symposium held at the Venice architecture biennial in 2014 declared, naming contemporary practitioners such as Hani Rashid, president of the Austrian Kiesler Foundation, as heirs to his legacy. Rashid’s works include a Manhattan tower block and a Dubai luxury hotel, as well as plans to build his technologically-updated version of the Endless House for a collector in Finland, a project that still remains on the horizon. Rashid’s Endless House, like Kiesler’s, is a conceptual formula that enables his other, less experimental buildings; but with the addition of post– to modernism, the sense of unfulfilled promise evaporates in favor of style-as-play.

This shift reflects in Helmut Jahn’s glass fronts at Potsdamer Platz as well: a curvy alternative surface to Renzo Piano’s adjacent hard corners. But the difference between the two turns out to be skin-deep: Modernist innovation, here as ever, means only a change of costume. Inside the Martin-Gropius-Bau we see the same reflection: a fascinating man and his astonishingly abstract sketches, set in dull frames and mobilized to a disappointing end.