“Beauty” and “dreamscape” are not buzzwords in today’s critical-art discourse. And yet they describe the Mori Art Museum’s Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation – Seeing, Conversing, Gift-Giving, Writing, Dining and Getting Connected to the World, an exhibition that’s nothing short of a reassessment of relational art. Mori museum director Fumio Nanjo notes the exhibition’s timeliness, linking it to the growing importance of human connections regarding both social media and new forms of connection, and regards these connections and bonds to have provided support after Japan’s 2011 earthquake. An Eastern viewpoint centered in Zen Buddhism is also cited, dramatically highlighted mid-show with an exhibition within the exhibition, Works for Relationality. Curator Mami Kataoka’s presentation of Lee Mingwei transcends the character of a broad mid-career retrospective, and explodes the popular reading of Lee’s practice as an Eastern example of “relational aesthetics.” In the West, we too often look for the dramatic cleavages in history. Kataoka expertly positions relational art as both rooted and timely.

A decade ago, one of the more popular and dominant topics of conversation in critical theory and the artworld in general was Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, translated to English in 2002. Go back to that time. Some of us were turning to the writing of Homi Bhabha and his “interstitial spaces” to get a more critical grasp of installation art. But this was something more. Bourriaud wrote that his concept of the “encounter” or “social interstice” was no less than “a radical upheaval of the aesthetic, cultural, and political goals introduced by modern art.” It also went beyond the dynamics of a “performative” act.

Relations? There were jokes. Critics like Hal Foster, Claire Bishop, Jacques Rancière, and Dave Beech resisted the term. Bourriaud’s micro-topias were seen as cliques resulting in insider excitement. Bishop felt that Bourriaud’s art of participation relied on conviviality as opposed to opening up venues of dissent and critique, and Rancière even saw it as socially divisive rather than inclusive to all. But eventually the penny seemed to drop, and the term took hold. Critics realized that the “aesthetic” was the very dynamics of our relations. Bourriaud leaned on his elected stable of artists to illustrate his points, including Liam Gillick, Vanessa Beecroft, Carsten Höller, Pierre Huyghe and most especially, Rirkrit Tiravanija, an artist who made Thai curry in the back rooms of galleries. Bourriaurd argued that as Pop Art was born from consumerism, and Minimalism emerged from the realm of industry, relational aesthetics emerged out of the realm of relationships. This was years before we even discussed or had experienced the contemporary online versions of social media.

Lee’s projects are to be carried out within the art institutions of galleries and museums, and Kataoka eloquently summarizes the projects, initially as read through the lens of Bourriaud. (Later, the view will be expanded): “Visitors enter these spaces and participate in ritualistic frameworks or simple instructions that Lee has prepared, whereupon artworks come into being by actually executing a series of actions. The significance of how these works emerge resides not within the act of giving a visible form to them – rather, it consists in the construction of relationships that resemble invisible threads.”

However, form remains. The danger of adhering too much to Bourriaud’s “shake up,” whereby we focus exclusively on the art as a duration of time centered on participation, is the loss of any serious assessment of Lee’s visual form. And, it’s one of sophistication that heartily deserves attention, particularly within the installations such as Between Going and Staying.

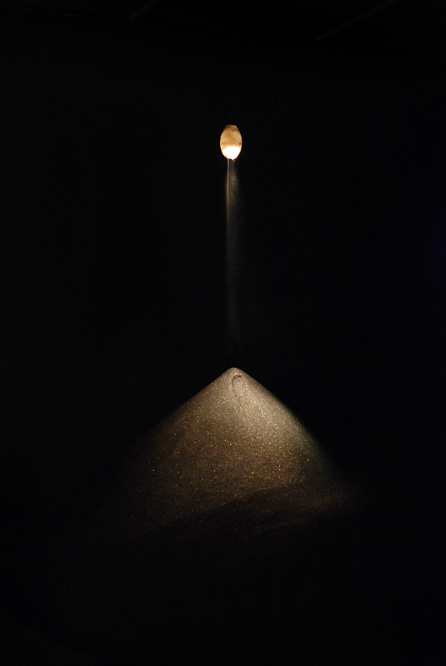

Extremely rare and special are those times we unexpectedly slip into a dreamscape while encountering art. They’re ineffable. How do you relate for someone, this feeling of falling into such a vivid and suggestive cue to the unconscious? How is it like entering sections of a Murakami novel? My first experience might have been in my very early twenties on my first trip to New York City. I was rounding a corner in the old MoMA and came smack up against Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy and then, ironically, The Dream in the next room. It happened a decade later when I stumbled into Tadasu Takamine’s installation, God Bless America at The National Museum of Art in Tokyo. A little over a decade later and just a few weeks ago, it happened for me again in the Mori Art Museum, walking into Lee’s Between Going and Staying.

I circled right back to the room where Lee was mending visitors’ garments. I tossed him one of the lamest questions you can offer an artist with no lead in, “Can you tell me about that piece?” pointing at the room with the installation. He smiled, and then proceeded to tell me about a dream. He was in a desert, it wasn’t too distinct, but stars were falling. There was a woman’s voice but he couldn’t make out words. He never brought up Homi Bhabha or used a word such as “interstitial,” but implied that it was one of those “in-between” places.

Many of Lee’s projects center on the gesture of gift-giving between strangers. The paradoxical element to his assigned roles is amplified in Japan, a country and culture that often regards itself as the “ultimate host.” Within the museum, Lee reverses this paradigm, where he, the foreigner (Lee is Taiwanese), is now the host with works such as The Dining Project and The Sleeping Project. Initially, we may cast Tiravanija as the extrovert, cooking and serving curry for large crowds in a gallery, and Lee as the introvert in a more intimate setting. But Tiravanija himself has stated that it’s the other way around. He feels like the introvert working backstage, whereas, he wrote of Lee, “it involves opening up your heart and mind to the person you’re making the meal for, and arriving at an understanding [of] him or her through dialogue and conversation.”

Lee wrote to me of the importance of The Dining Project as an intimate encounter between artist and participant. The event takes place exclusively “one on one,” and is not viewed by observers while the meal takes place. This is due to Lee’s personal preference for intimate and personal exchanges between strangers. Within the museum, this involves Lee and visitors, who may engage with him in conversation or even be selected to join him in a private meal or shared afterhours evening of conversation and, at some point, sleeping.

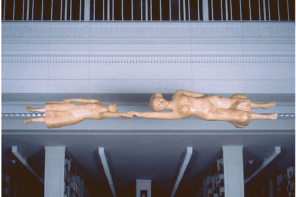

Ephemeral gestures and visual presentation are perfectly wed and nuanced within Lee’s works, such as the Nu Wa Project where a kite is released into the sky suggesting its healing by a goddess. The Moving Garden works as both a dramatic installation within the museum space and an extended relational event employing the simple gift of a flower from a visitor to his exhibition to a stranger on the street. I keep coming back to a word that doesn’t come up very often in contemporary art, beauty. We’re critically conditioned to be uncomfortable with that word, but maybe Dave Hickey (an infamous proponent for the maintained relevance of beauty in critical art appraising) issued a wanting snake that’s at play in the institutional space, now, in this case slithering through a Zen garden. Lee’s practice is much more than simply conducting social activities and experiments within museum and gallery settings. There is a refined, sophisticated visual dimension to the work I fear gets overlooked. Lee confirmed this within our correspondence, “Beauty, in both physical and emotional forms, is central to my work. The other essential element is ‘tension’, which magnifies Beauty.”

This expert refinement of form often draws on the dynamic flow between the past and present. (I’ll add that Bourriaud’s indebtness to the concept of time in art-making has not often been given its due.) But Lee’s relationship with the past is less archaeological a model than an act of cross-cultural engagement. His project Through His Master’s Eyes involved inviting both Western and Eastern artists to reproduce works by the Qing-dynasty Chinese painter, Shitao. This exchange is far from cynical and brings about questions of visual inheritance, asking if, indeed, a relational dialogue is possible with a historical predecessor. Lee spent six summers in his youth at a Ch’ an monastery, where his formal training in Chinese literature and painting began. His studies focused on the idea of the void in mainly Song-dynasty Chinese painting.

Lee’s critical acknowledgment of the past, with an emphasis on that of Asia, is shared by curator Kataoka. Her expansion of Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics suggests that it should, critically, include Lee, but also many others such as Ozawa Tsuyoshi, D.T. Suzuki, John Cage, Lee Ufan, Yves Klein, Allan Kaprow, Tanaka Koki and even more distant figures such as Imakita Kōsen and eighteenth-century Zen priest, Hakuin. The exhibition-within-the-exhibition, then, Works for Relationality, features examples such as a Hakuin ink-on-paper painting, Sekishu (One Hand), ostensibly referring to the Zen kōan. Though meant to convey profound transcendental concepts of timelessness, Hakuin’s playful wit is often overlooked. Kataoka extends the relational dialogue through history by including other examples such as Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void (1960) and Ozawa Tsuyoshi’s Vegetable Weapon series of 2001. It’s not easy, at least for a Westerner, to grasp that relationships and connections can include a concept of “nothingness” and “emptiness.” Lee described his time in the Ch’ an monastery, for instance, as an environment of “extreme minimal[ism].” “My teacher would use the simplest natural object such as stones, plants, or snow to share with me the sense of Beauty in everyday encounter,” he writes.

Not to be confused with Western essentialist reading on minimalism, these installations succeed due to their bold, visual simplicity and the confidence of this gesture, whether it was the falling black sand lit iridescently in Between Going and Staying, the black pebbles placed around the dinner setting in The Dining Project, and the swept patterns left in Guernica in Sand.

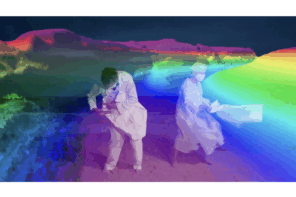

Kataoka posits that “the reassessment of ‘participatory art’ from a Buddhist perspective promises once again to reopen its discussion to a wide context.” Buddhist concepts like pratītyasamutpāda (the chain, or law, of dependent origination) imply a causal relationship of good and bad luck in daily interchange, connected along a temporal axis. Being centered and aware within the present moment also implies an acute awareness of transience and suffering. As the museum director acknowledges, part of the significance of this exhibition was the recognition of healing connections in Japan following the earthquake of 2011. Further, Lee’s The Mending Project originated from the trauma of his partner losing hundreds of colleagues in the World Trade Center. His Guernica in Sand was inspired by American bombings of Iraq in 2003, and obviously draws from Picasso’s artistic response to Nazi air raids in Spain in 1937. In Lee’s Guernica, the work is both walked upon by viewers and swept by performers including the artist himself, keeping its form in flux just as Tibetan sand mandalas are destroyed by the Buddhist monks who create them. Kataoka writes, “To be conscious of the mutual interdependence between all things is also to be aware of the temporal relationships of cause and effect, such as relationality and the in-between.”

The digitalized, virtual space of this very website, it could be argued, is an example of the in-between. One might ask if art criticism and theory are starting to pay more attention to the concepts of the in-between and the void. The theorist Boris Groys writes that as previous eras, signaled by Warhol, Judd, and Duchamp, demonstrated the severing of the body of the artist from the body of the artwork, our current internet-era has only further alienated us and our bodies from the artwork and its multiplying, fragmenting image.

Most of us experience how the fragmentary multiplicity inherent to online social phenomena leaves us alienated even as it affords us new connections. Does relational art, as Bourriaud suggested, act as a proposal to live in a shared world, or fool us, as his critics maintained, into producing in micro-communities? Fumio Nanjo and Mami Kataoka provide the venue for something extraordinary with this exhibition at the Mori Art Museum. They successfully extend the breadth of relational art and its expanding history through Works For Relationality and the dramatically presented relational projects and installations of Lee Mingwei bolster relational art as a platform to contemplate the ephemeral and the void. I would argue these are examples of beauty in time and space as well.

1 Comment