Guy Maddin’s latest exhibition finds the artist in a splendid mood, if preoccupied by the subtle, inescapable persistence of his loneliness. Maddin and his life/art partner Julia Anne Leach have taken to collaging together – as much as they can and for hours on end, according to a printed conversation attached to Front Tooth and Wonder Bread, at Lisa Kehler Art + Projects, in Winnipeg – and, by their own account, they’re having a wonderful time. LKAP presents a much-distilled selection of twenty-six works just from Maddin’s half of this abundant production, in which he surreptitiously interrogates a lurking and persistent sense of alienation.

The show’s title invokes a childhood innocence so campy and exuberant that gallery-goers can’t help but steel themselves for an untimely blast of sardonic, Norman-Rockwell-on-a-cereal-box nostalgia. But the work appears to be mostly free of such mordant satire. In fact, Front Tooth and Wonderbread refer to two types of off-white paint that Maddin discovered back in his house-painting days. (Other favorites from the palette include “Seagull Breast,” “Old Snow,” “Frog Throat,” and “Eisenhower.”) Maddin relishes these fortuitous pairings, and the exhibition is primarily a celebration of things that go together unexpectedly well. Like a parade of lovers, the images are sweet and satisfied; they seem to rejoice in their own existence.

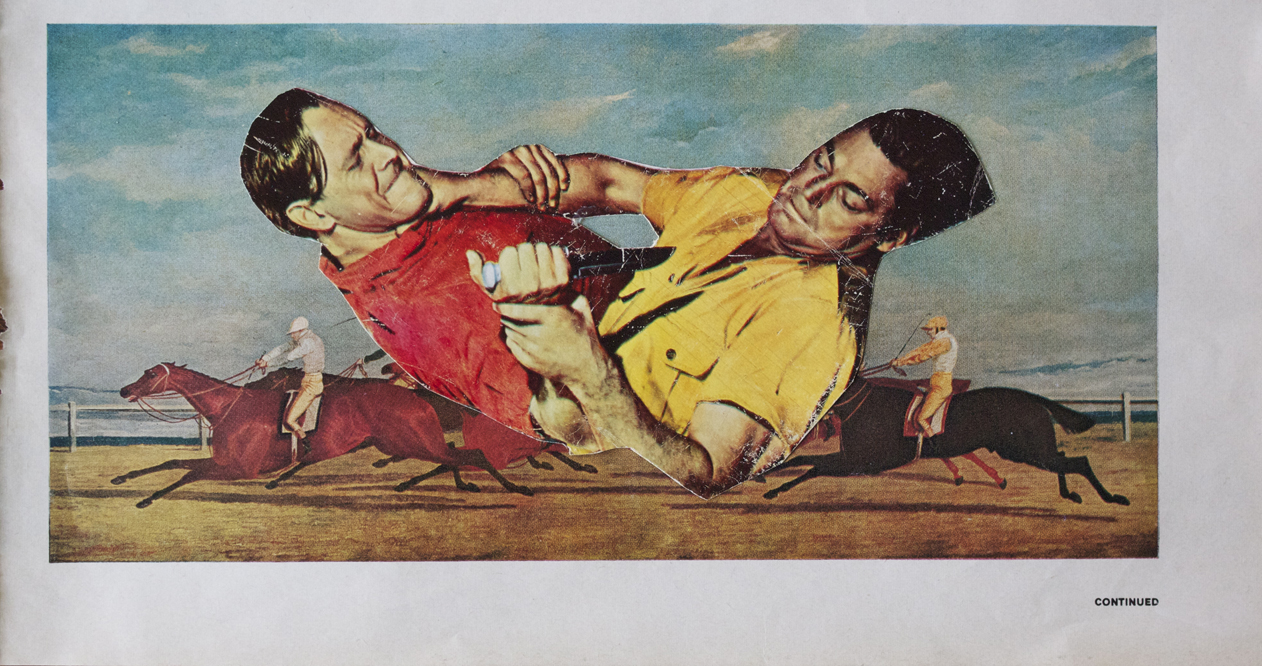

The mood of the exhibition owes much to this improvised search for aesthetic serendipity, but also to the source material, that which you would expect to find at estate sales or second-hand bookstores: out-of-date science textbooks, old magazines miraculously un-mulched, maybe a neglected photo album. Maddin makes several concerted references to these forms of print publishing in the work. For example, Untitled (Knives), an elegantly arranged knife fight atop a horse race, has the word “CONTINUED” in the bottom right corner, directing the viewer to another page that was presumably lost to Maddin’s cutting-room floor.

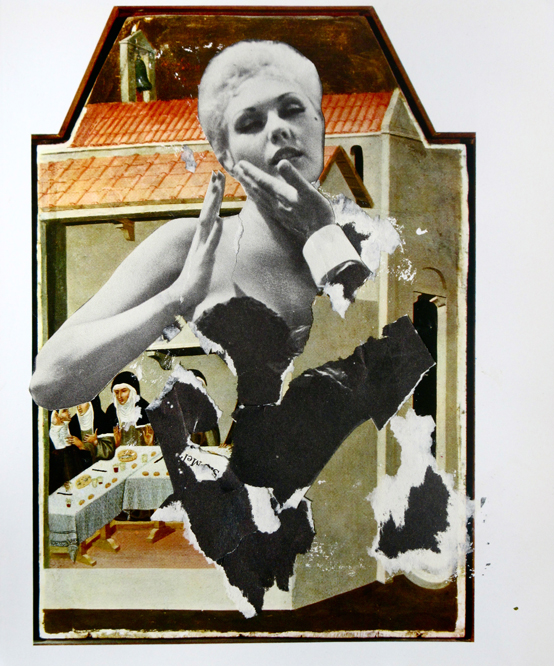

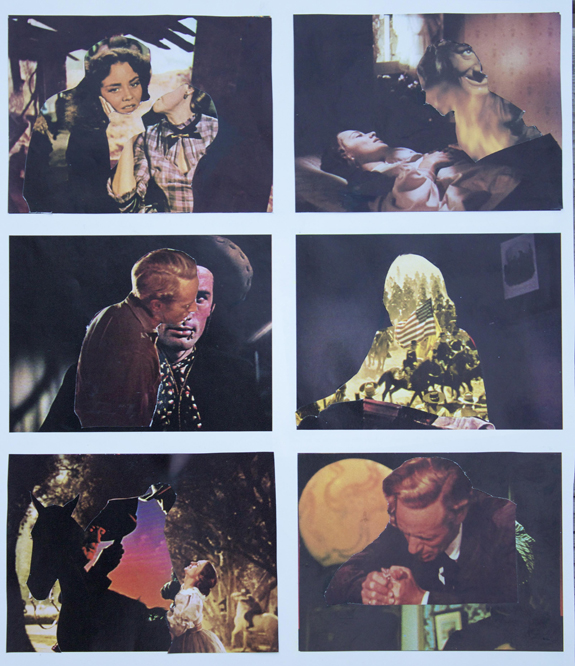

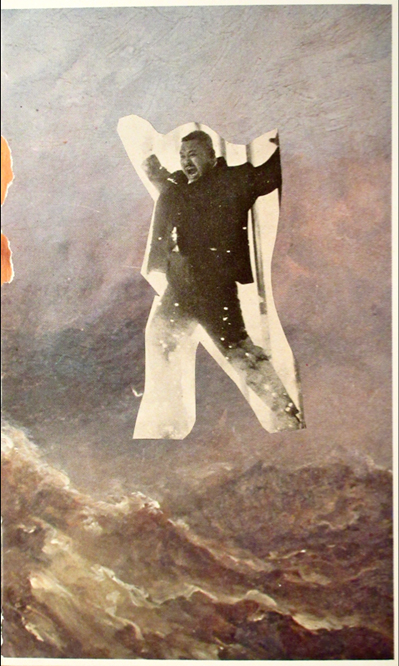

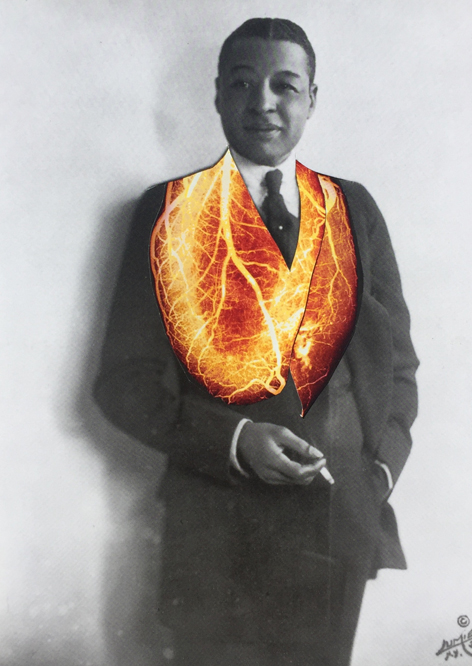

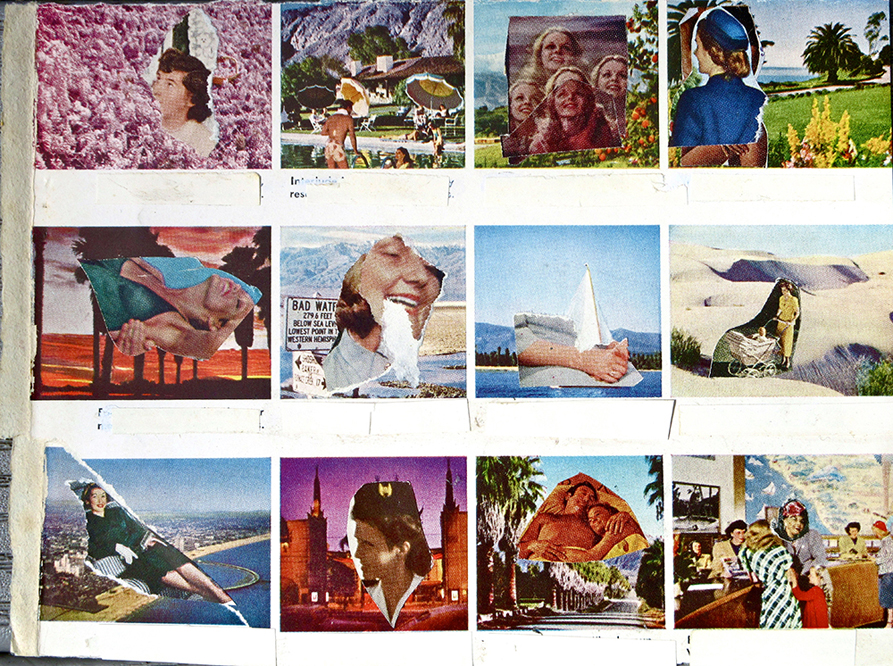

With such maneuvers, Maddin nudges us to contemplate the changing paradigm of image distribution – “How ponderous it must have been, to turn a page!” – though mainly these paper antiquities serve as set pieces for the show’s nostalgic drama. In a series of grouped collages that Maddin terms storyboards, he evokes the 1960s North American bourgeoisie, happily banging out the baby boomer generation behind the scenes, and otherwise fomenting tourism with their big smiles and jumper dresses. Under vitrines, we find another series disporting cultural icons of the period, like Kim Novak and Jackie Kennedy, mounted atop Renaissance religious paintings.

All this retro styling looks nice, but risks little. The chronological distance of the source material neutralizes whatever political threat might be achieved by emphasizing gender or class stereotypes, or highlighting triumphant displays of whiteness. Maddin shows us many images of the type of men and women whose memory the Right likes to eulogize, performing their most jubilant, frolicsome selves: playing around at the beach, adventurously checking in at a hotel, reclining on a sofa with an air of frisky fun. Are you happy for them, or not? Either way, it’s possible to have a good time observing these historical bodies enact aspirational states of being, while easily deflecting into abstraction the blunt trauma of their still-ascendent conventionality.

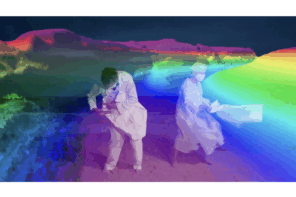

Maddin seems to need the safety of reaching back half a century for referents, in order to allow a melancholy to emerge. He harnesses that temporal distance and the weird blend of familiarity and foreignness it creates, in order to convey a sense of personal isolation. In his films, Maddin has often used cleverness and mischief to corral strong emotions, and in a witty composition at the outset of Front Tooth and Wonder Bread, he alerts us to the sense of alienation that hangs over the show. The first work is Untitled (Rainbow), an image of a rustic mountain pass in which a pixelated silhouette, cut from some sort of heat map, stands in the foreground and takes in the view. It’s a scene of wild natural splendor, ripped from some old sporting-life magazine, and in the middle hovers an incongruous observer from a different medium, a different domain, a different era. It’s impossible not to see this piece as a cipher, for both artist and viewer. Maddin has us intrude on his romanticized past in the guise of this incompatible sightseer.

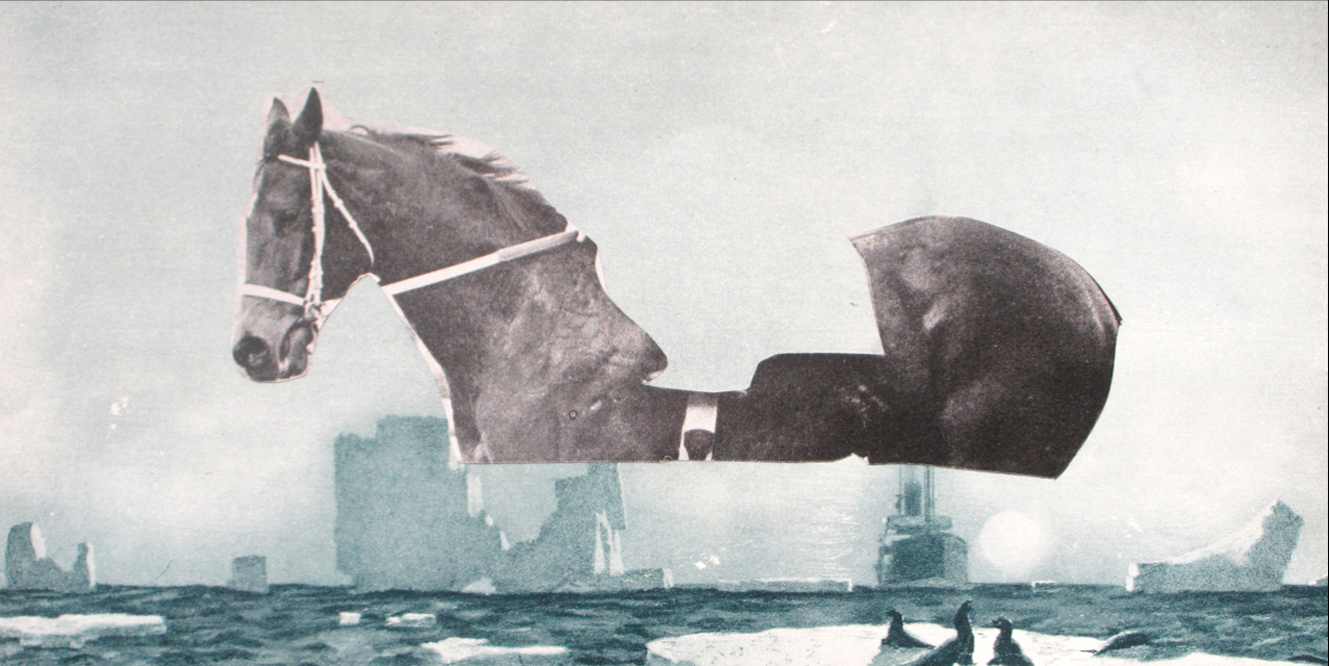

Works like this one will make you feel smart because they’re so intelligible. The trick is keeping things simple. Maddin rarely reaches far for his collages. Like Untitled (Rainbow), most of his pieces consist of two distinct images, one a character and the other a setting, divided into foreground and background, and arranged in a straightforward, balanced composition. In his interview with Leach, he calls this strategy a “bad habit,” but I prefer its directness to the alternative. What could be worse than collage that’s full of striving?

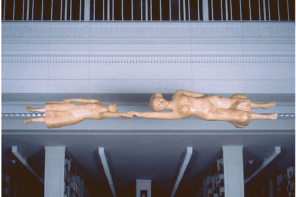

In the documentary Waiting for Twilight, about the making of the film Twilight of the Nymphs, Maddin says, “I try to keep things childish on the set, because I like movie-making to feel like a child feels when he or she is just absent-mindedly cutting up pieces of paper or pieces of food and gluing them onto big pieces of manila, totally unaware of how much time is passing.”

This image of a small child directing a movie certainly falls within the broad concept of collage that Maddin and Leach discuss in their interview. Their definition includes things like “chronologically impossible cover tunes” (Nina Simone covering Rihanna, or Leadbelly playing Beyonce), the poetry of John Ashberry, and the artist’s latest film work Seances, a random film-generating machine with algorithmically-derived non sequitur titles.

Collage even includes the strange juxtapositions produced by the real world. Imagine, for example, a Bengal tiger and a baboon on the side of a highway in Ohio, at dusk. Maddin and Leach talk about coming across that exact scene, after an amateur zookeeper decided to release all his animals. What made it so perfect, apparently, was the quality of the light. “Those animals, as startling as they were, belonged in that landscape,” Maddin recollects. Though, of course, they didn’t at all, and it’s actually a tragic scenario. But that fleeting transformation is the key to this whole endeavor: making things belong when they don’t. It’s about taking two things that on their own are lost or forgotten or messed up, and making them look perfect.

1 Comment