A common analogy for a sprawling, hypnotic, and potentially fruitless search on the Internet is the rabbit hole: dark, long, and terminating in a surreal zone. It’s a place where logic falters and conspiracy theories run fertile. Websites like 4Chan and 8Chan provide perfect fodder for phenomena such as QAnon, the right-wing conspiracy theory that posits, among other things, that Robert Mueller was appointed by Trump to investigate the Democrats and members of the “global elite” of world politics and Hollywood, who are engaged in nefarious pedophile rings. Lest we dismiss this fringe as a harmless outgrowth of internet culture, consider that Cesar Sayoc, the Florida man who mailed more than a dozen pipe bombs to vocal critics of Donald Trump, including the Clintons and George Soros, spouted similar conspiracy theories on social media. Climb out of the rabbit hole, and you may find yourself staring down the barrel of a gun.

The timeliness, then, of Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy at the Met Breuer, cannot be overstated. Rather than addressing today’s Internet-exacerbated conspiracies, the exhibition reflects on conspiracy in the latter half of the 20th century, with a particular emphasis on American art. In highlighting the prevalence of conspiracy rhetoric in the United States and its influence on the American culture industry, the exhibition offers solid perspective on our turbulent times. Its dominant mood is nostalgic rather than paranoiac; conspiracy, as the exhibition demonstrates, has long been woven into the fabric of the United States. In reflecting on particular histories while minimizing, abstracting, or omitting others, the curators suggest that conspiracy’s cultural resilience is at least partly because it functions as a conduit for nationalist sentiment.

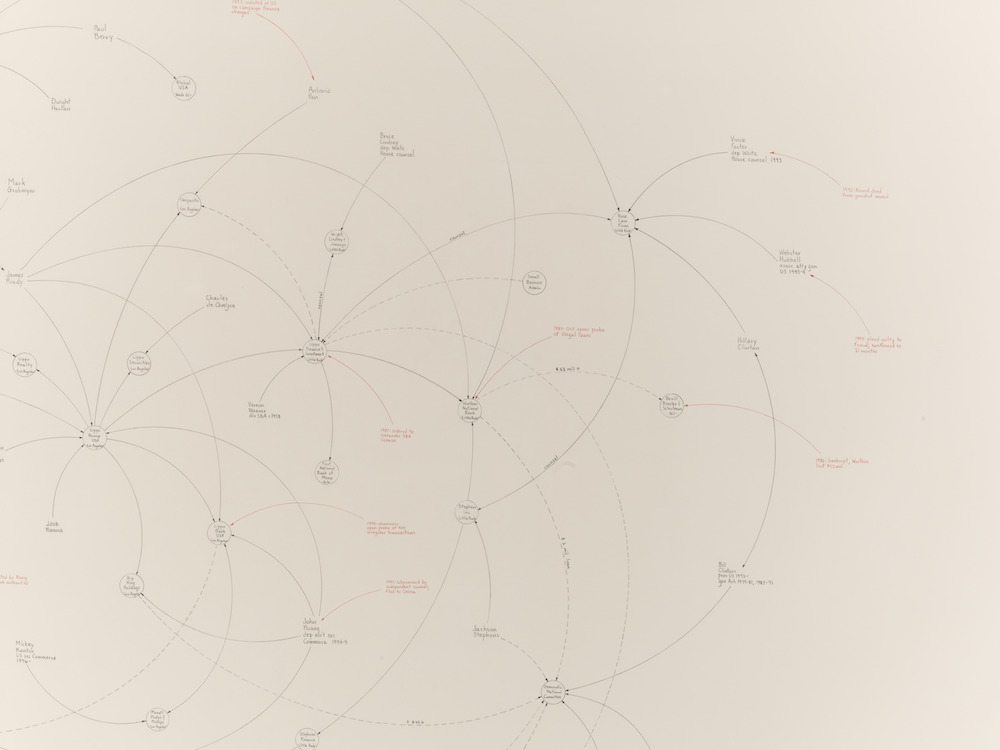

Mark Lombardi. “Bill Clinton, the Lippo Group and Jackson Stephens of Little Rock, Arkansas (5th version)” (detail), 1999. Courtesy the Lombardi Family and Pierogi Gallery.

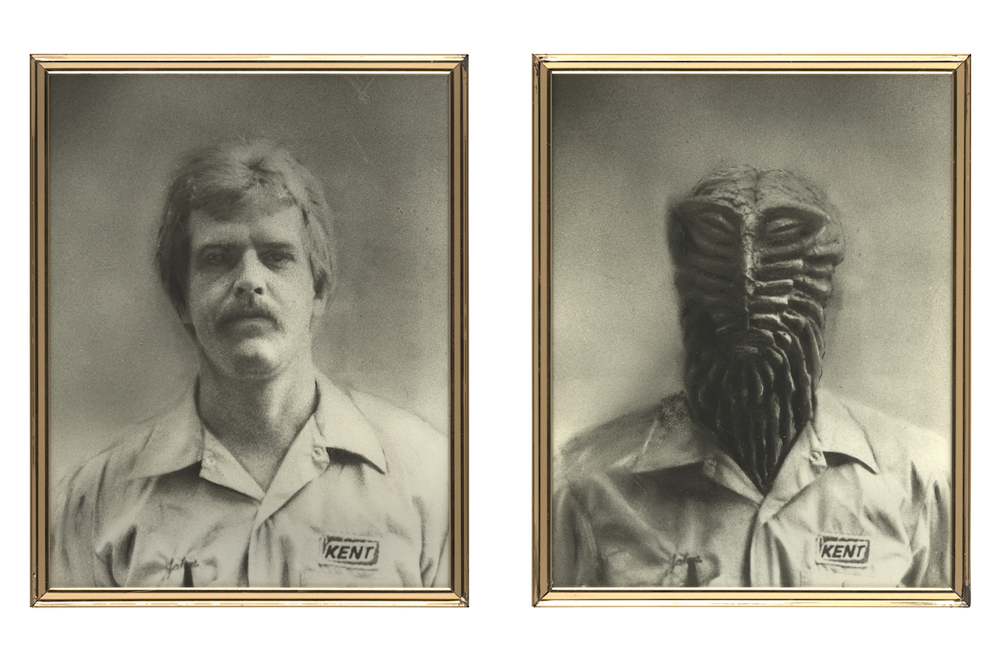

The show is divided, perhaps too neatly, into two complementary sections. Its first half focuses on artists that directly address political and social issues while drawing from the public record; the second half veers into more fantastical, speculative territory. The distinction here is meant to emphasize the difference between conspiracy – that is to say, real-life events that were initially met with skepticism and often later found to be true; and conspiracy theory, with its connotation of fabrication. Despite the exhibition’s claims to highlight ambiguity, the delineation between the complementary halves of the exhibition exposes an authoritative register: while certain histories are taken to be true at face value, others are relegated to conspiracy theory, but the calculus of this decision remains vague. In the first half, works like Mark Lombardi’s BCCI-ICIC & FAB, 1972-91 (4th Version) (1996-2000) meticulously trace connections between drug smugglers, politicians, and financiers. In his 1971 investigation of real estate moguls Sol Goldman and Alex Di Lorenzo’s use of shell corporations to obfuscate their holdings from tenants’ rights groups, Hans Haacke employed a similar forensic mode and display of evidence. When these works were initially exhibited, at the Whitney and the Guggenheim, respectively, they were confronted by the authoritarian infrastructures they critiqued: Lombardi’s show prompted a visit by the FBI to the Whitney, while Haacke’s solo show at the Guggenheim was cancelled and its curator fired. Evincing the potential for art to function as effective political critique, such works demonstrate how research-based practices were mobilized by the pervasiveness of corruption.

The nostalgia that pervades Everything is Connected is of the kind that Svetlana Boym describes in The Future of Nostalgia as “restorative.” It results from eliding dominant cultural narratives with the belief that such narratives are indelibly true and convincingly simple. According to Boym, restorative nostalgia “knows two main narrative plots – the restoration of origins and the conspiracy theory, characteristic of the most extreme cases of contemporary nationalism fed on right-wing popular culture.” The conspiratorial mode, argues Boym, is nostalgic for a return to a simplistic battle between good and evil, an erasure of modern circumstance, and a “return to home.” Notably, nationalist movements fueled by nostalgia for an untainted past and the spread of conspiracy theories in support of this nostalgia often peak after revolutions. In the American case, it appears that the rise of conspiracy theories were fed not by militaristic revolutions, but cultural ones. With the first heavily televised war raging abroad, and battles around women’s liberation, civil rights, and sexual politics erupting at home, the ailing conservative media doubled down on their efforts to mobilize against a perceived liberal bias in the media and revitalize the Republican Party.

While Boym’s arguments map easily onto the current state of right-wing nationalism, the exhibition demonstrates that conspiracy theories have been no less seductive to left-leaning milieus. The artists in the exhibition’s final gallery in particular, including Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, John Miller, and Sue Williams, developed their practices at the experimental, liberal-minded California Institute of the Arts, where their use of various video and mixed media technologies scrutinized Regan-era politics and culture. Kelley’s Untitled (Government and Business) (1991) coalesces blotchy, dripping streaks and curlicues of black paint around an entanglement whose form is as nebulous as its titular entities. For Kelley and his CalArts cohort, the fabulist enterprise of conspiracy became a means to counter an increasingly neoliberal ruling class through the late 1980s. By then, the machinations of power, increasingly absolved into corporatism and globalization, became more obfuscated than they were in the 1970s, and as a result, felt ripe for suspicion.

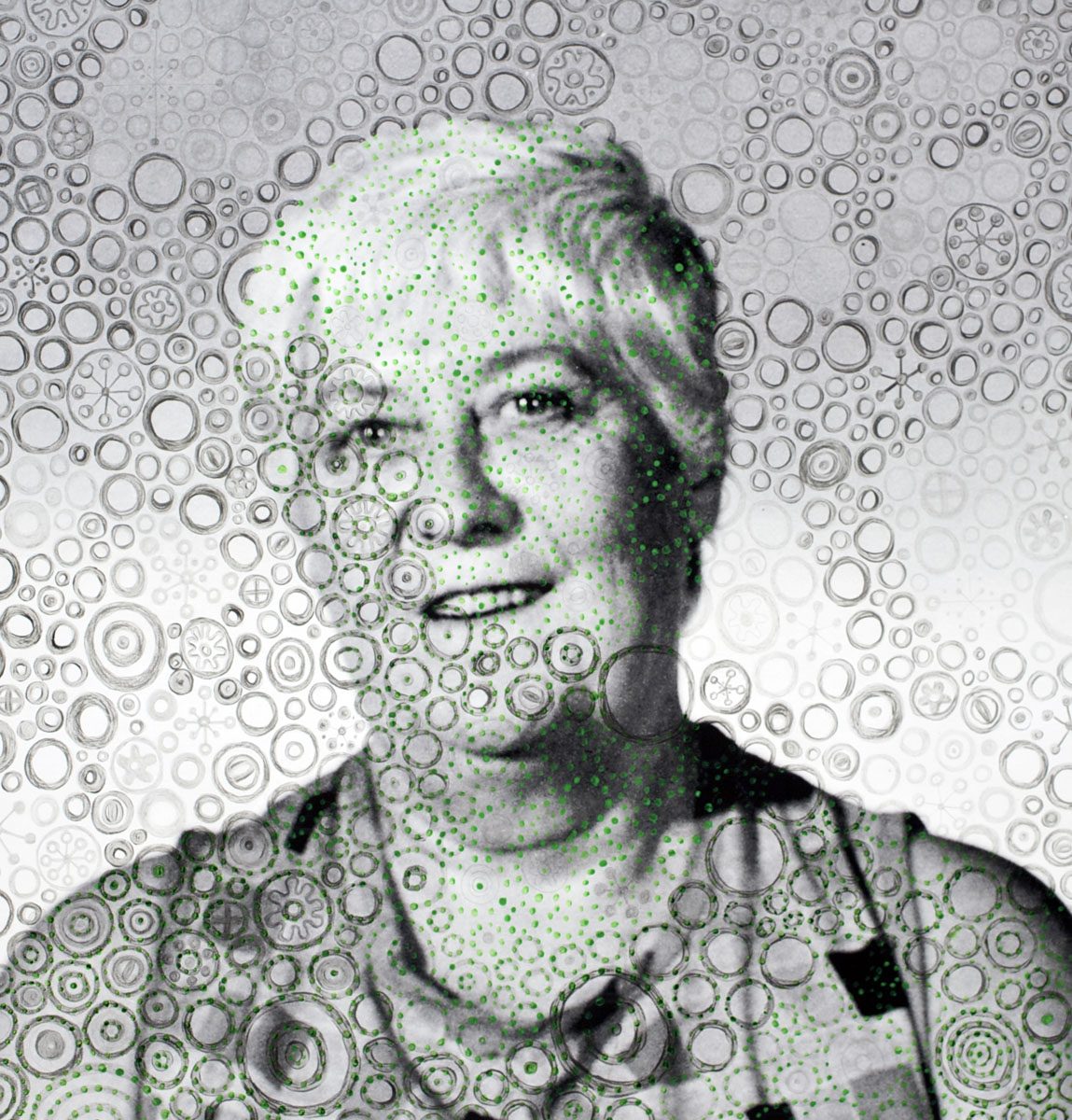

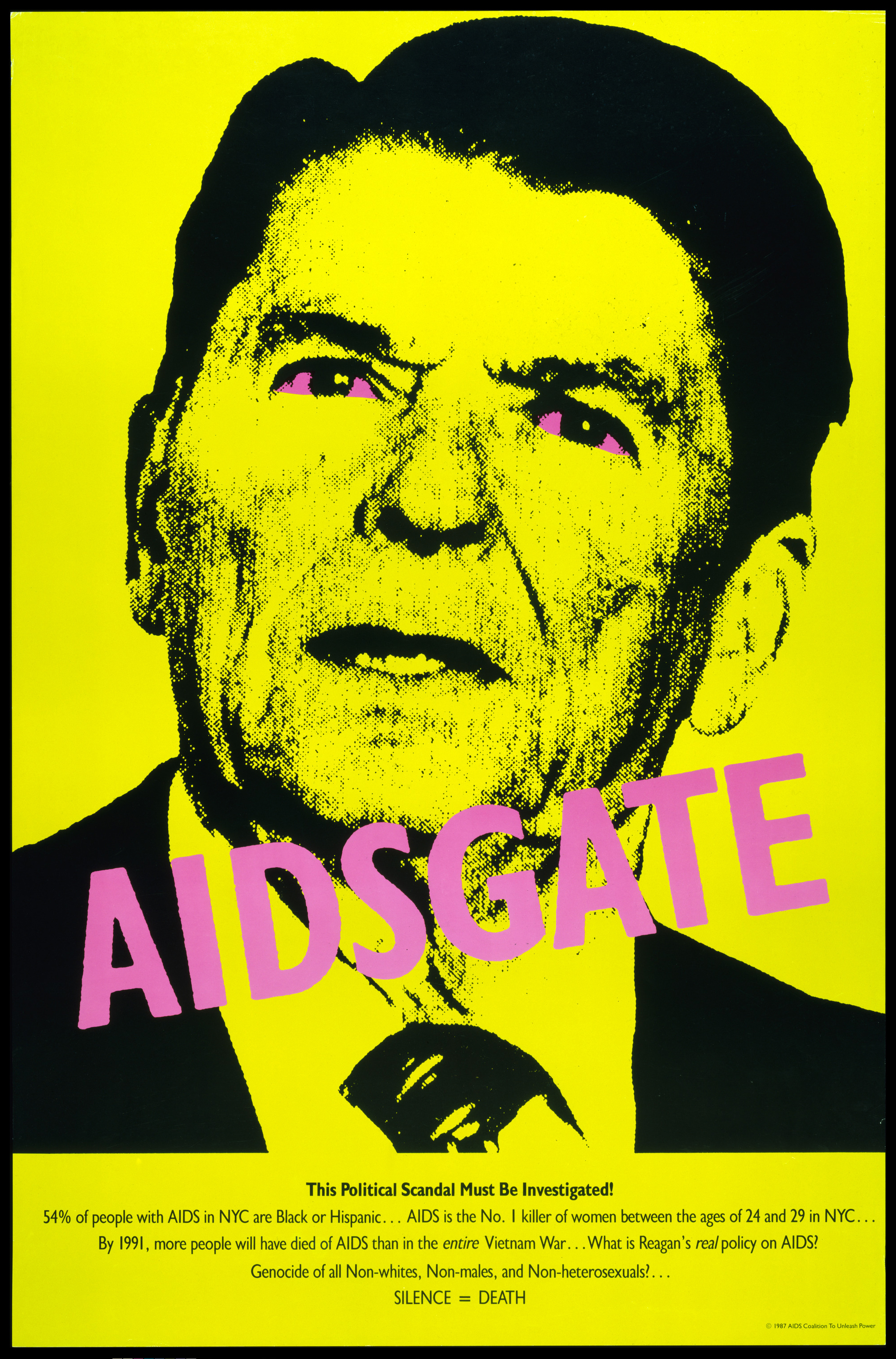

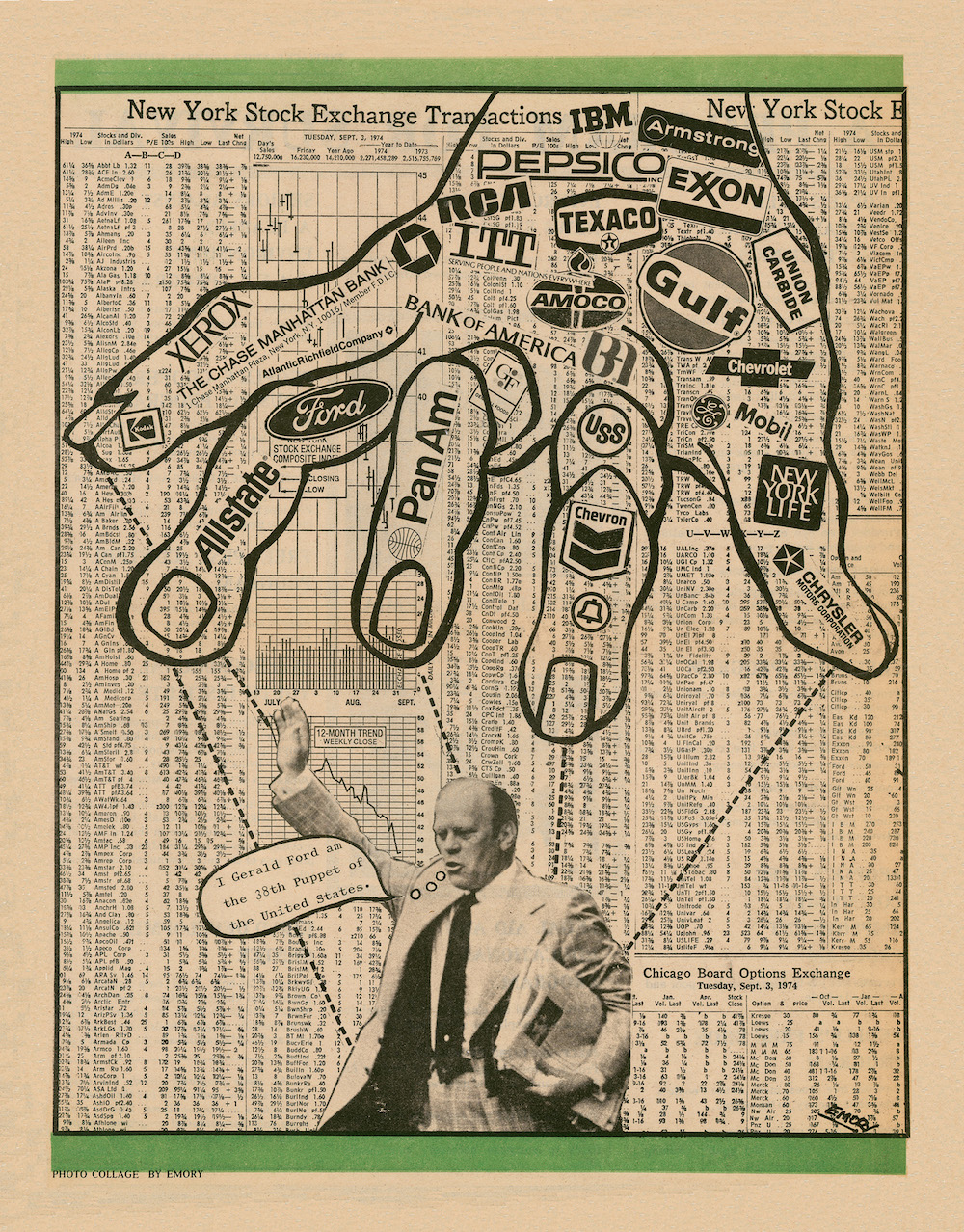

Boym’s “restorative” nostalgia feels especially pertinent to an exhibition in which the marginalized histories of America serve as footnotes: Of the 33 artists and groups exhibited, the overwhelming majority are white men; all but six are American, and none are under 40. Conspiracy has been the concern of a swath of American artists for at least a half century, but its violence has affected a much wider demographic than the exhibition suggests. The most engrossing and affecting moments arrive in a single-channel video by the collective Videofreex of Fred Hampton, delivering a speech to the Black Panther Party in Chicago in 1969. In it, Hampton speaks of the Party’s services to the impoverished citizens of Chicago, for whom they provided free breakfast for children. The work is chilling not only because of Hampton’s oratory prowess and condemnation of American imperialism, but because we know that Hampton was murdered by Chicago police shortly after it was filmed. The video shares a wall with posters from AIDS activists such as Avram Finkelstein and Gran Fury; nearby are Emory Douglas’s graphic covers for the Black Panther Party’s main newspaper.

“If you were a minority or a politically active member of the counterculture in the late 1960s and early 1970s,” notes co-curator Douglas Eklund in the exhibition’s catalogue, “paranoia was a defining quality of your existence.” Eklund fluidly addresses the significance of identity politics and citizen journalism, respectively, and their relation to conspiracy. His sharp observations, though, make the reticence of these themes in the exhibition all the more disappointing. It often feels like a pedant’s chore to point out gaps in historical surveys; exhibitions at large institutions such as the Met are planned years in advance, and they can’t be expected to be completely topical or comprehensive. But at a time when violence is a steady and rising threat, and the state apparatus is led by a callous and cruel cohort of thugs, the pervasive nostalgia of Everything is Connected threatens to fall into the same nationalistic impulses that many of its artists fought so vigilantly against.

And yet the exhibition’s failures, its omissions of important struggles, makes it even more worth seeing. The current hellish political landscape of America snaps into focus and, with it, the lure of conspiracy, paradoxically, becomes more lucid. But, as Richard Hofstadter argued in his 1964 Harper’s essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” paranoia, and its manifestation in conspiracy, is embedded in the American DNA. Tracing a history from the anti-Masonic movements of the late 1820s and 1830s, to anti-Catholic sentiments, to his right-wing contemporaries in the 1960s who felt that America had “been largely taken away from them and their kind” by “cosmopolitans and intellectuals,” Hofstadler concludes that the paranoid style takes hold when people recognize their impotence in the face of power. Without access to political decision-making, the disenfranchised find their suspicions about the sinister offices of power confirmed. What’s contested here is the definition of disenfranchisement. Who defines this narrative? Is it those subjected to institutionalized racism, sexism, poverty, and discrimination, or those who bristle at a threat to their dominance? Like Boym, Hofstadler recognizes the appeal of a good narrative plot, the thrill of a persecution fantasy. The trouble is, as this exhibition inadvertently demonstrates, the story is hardly ever this neat.