Though history is said to have been written by the victors, one might be forgiven for casting doubt on this particular adage in Richmond, Virginia. The former capital of the Confederate States of America and the current capital of its state, Richmond is littered with monuments that lionize the usual suspects – Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson – alongside lesser-known local heroes, such as Confederate J.E.B. Stuart. It’s on this palimpsest that the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts rests, with a collection that boasts the likes of Matisse and Modigliani. Prior to the opening of the museum in 1936, the grounds housed a residential complex, complete with a chapel, for destitute Confederate veterans of the Civil War. Amidst this backdrop of Southern gentility and patriotism, contemporary black art takes on a unique verve that sheds light on the narrative of history and its traces in American life today.

***

Four-score and a few months after its inaugural opening, the VMFA is hosting one of the most celebrated black artists of our time. Kehinde Wiley’s mid-career survey (grandly titled a “retrospective” for the 39-year-old), A New Republic, whose previous iteration at the Brooklyn Museum in 2015 sparked controversy (even its criticism received criticism), claims its hold in the South. The exhibition is slated to travel to four more museums in America, and each one comes with its attendant challenges. For the VMFA, the issue arrives in a question of how race, narrative, and history coalesce and collapse within its particular exhibition space. Wiley’s show presents the opportunity to consider how institutions must juggle their own pasts alongside increasing attempts toward diverse representation.

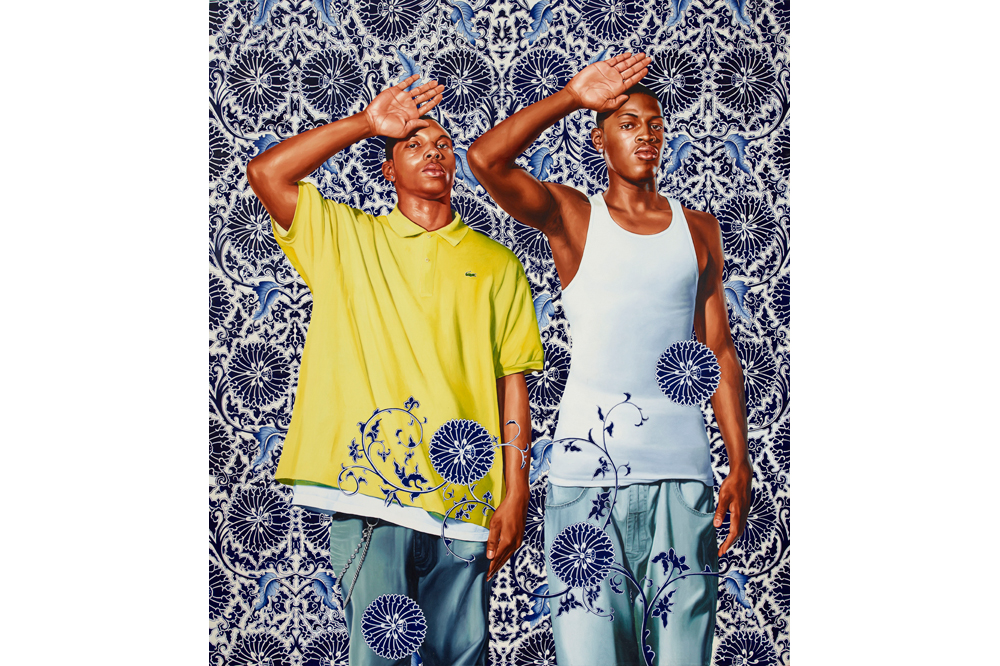

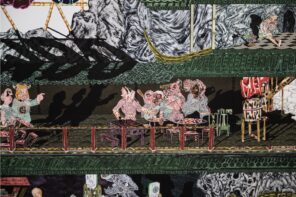

Wiley is, of course, no stranger to history. The Yale MFA-educated artist rose to dizzying acclaim for massive portraits of black male youth standing in for the subjects of Old Master paintings. Cast from the streets of Harlem during Wiley’s residency at the Studio Museum in 2001, the men were asked to select a historical painting, largely Baroque and Renaissance, to mimic or “inhabit.” The result is a shifting of the canon, a postcolonial nod to the absence of black figures in the long history of portraiture. The transparency and straightforward legibility of Wiley’s methodology, however, often flattens the complexity of his subjects, resulting in paintings that limit critical imagination, rather than extend it. Wiley’s revisionist history is, as Eugenie Tsai, curator of contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum, notes in her introduction to the catalogue, “corrective, even utopian,” insofar as he critiques a Eurocentric approach to art history and centers, instead, on its outskirts. These peripheries take on a global scale in his series The World Stage, for which Wiley took his street-casting practice from Harlem to more far-flung locales including China, Brazil, Senegal, Nigeria, Israel, India, and most recently, Haiti and Cuba. Though he extends the scope of the project, Wiley maintains the signature style of his previous series: large canvases, ornate frames, and mostly black male subjects.

Truly, it’s difficult to fully commit to the idea that Wiley’s grand historical paintings are indeed corrective in themselves. The intricate backgrounds offset the subjects to flatly echo grandeur, power, wealth – but the disparity between the subjects and their staged settings prevents our ability to suspend disbelief. As Chloe Wyma notes, the source paintings into which Wiley inserts his urban subjects are too far in the past to convincingly comment on the subjectivity of black males in contemporary America – and even less so of those in the various nations that inspired The World Stage. His subjects are simply figures ensconced in fictive spaces that are republics unto themselves, stripped of context and history, distanced from the viewer in their frames. This is Wiley’s ultimate shortcoming: by leaning on the trappings of historical portraiture and contemporary pastiche, he traps his subjects into a flattened visual shorthand for urbanism. Their subjectivities are defined by negation, to their opposition to the luxurious backgrounds and the historical context of their source paintings, stripping them of the very power and autonomy that he claims to imbue them with.

Wiley’s consideration for power and history, however, does lend itself to curatorial experimentation. In an effort to encourage visitors to view the museum’s larger collection in addition to Wiley’s spectacle-laden oeuvre, Sarah Eckhardt, curator of contemporary art at the VMFA, provides visitors with references to works in the museum’s collection that are of the same time period and style as the source paintings from his portraits. For the ordinary visitor, Eckhardt notes, it is “difficult to understand that conversation he’s having not only in the exhibition but in just one work, and this gave us a chance to help people understand.” Walking through the collection, it’s easy to see where the historical quotations can make sense; the museum boasts African cloths from Ghana, large Rococo and Baroque portraits, and Indian miniatures – all germane to Wiley’s machinations.

More difficult to draw from the museum’s collection is the connection to black representation in Virginia’s Confederate past – and perhaps, this is the point. The disconnect between the references to grand European portraiture and the more humble portraits of antebellum America sets in place a basis for contemplating the historical context of Richmond as it pertains to contemporary black art. Jefferson Gauntt’s portrait of Violet Anthony from 1832 is the most direct and relevant comparison. Violet, known colloquially as “Miss Turner’s old slave Violet,” was one of the last slaves in Philadelphia, a northern city in which slavery was legal until 1847. Identifiable as West Indian by her coral necklace, Anthony’s face is lined and wrinkled, her features and comportment given an attention to detail that is comparable to the sculptural quality of many of Wiley’s subjects. The museum’s contemporary collection, however, holds a more confrontational address to its provenance: Sonya Clark’s 2010 work Black Hair Flag weaves thread in the form of Bantu knots and cornrows through a Confederate flag, tying together the complex histories of a black subjectivity and a nation that would flatly deny its presence. Clark’s work, much like the work of her contemporaries Kara Walker and Sanford Biggers, engages the history of black subjects as the history of America, drawing upon the history of slavery to indicate that American nationhood itself is contingent upon the remembrance of black lives.

Wiley’s parallel to Clark can be found in his early work, before he fell to the pomp and grandeur of his more commercially-viable painting. Conspicuous Fraud #1 (2001) presents the viewer with a black man in a business suit, set against an aqua background, whose thick, knotted hair springs from his head and billows across the canvas like clouds in a gesture that suggests a boundlessness betraying the limits of a body. These earlier works tap into a nuanced understanding of black life in contemporary America, and none does so more poignantly than Mugshot Study (2006). Taken directly from a crumpled mug shot that Wiley found littered in Harlem, the painting is an exercise in precision and, more importantly, in compassion. Much commentary has been passed on Wiley’s subversion of hyper-masculine stereotypes of the black male, particularly regarding their depictions against effeminate floral patterns. But the subject of Mugshot Study achieves a softness that the historical pastiches do not because they are stripped of the gaudy ephemera to reveal, plainly and quietly, what his more recent portraits seem to lack: an empathic speculation of an inner life.

***

In 1993, the Commonwealth of Virginia agreed to lease the chapel on the grounds of the VMFA to the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who proudly flew the southern cross atop its cupola. When the lease was renewed in 2010, the museum stipulated that the flag be removed from the chapel, prompting a group of zealous Confederate sympathizers to protest on the sidewalk along the museum (they are forbidden from doing so on the actual grounds) with astonishing regularity, every Saturday since at least 2011.

It was on a warm Saturday afternoon that I saw these protesters – aptly dubbed the Virginia Flaggers – while I stood inside the second floor of the museum, having just exited the Wiley exhibition. It was at once jarring and eerily familiar, which is the way history usually functions, in this republic, and in those to come.