“The closer we come to the danger, the more brightly do the ways into the saving power begin to shine and the more questioning we become. For questioning is the piety of thought.”

-Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology (1954)

Artificial Intelligence has been breathlessly covered in the media over the past year, starkly contrasting alternative futures: a dystopia of killer robots-run-amok contends in the popular imagination with a Keynesian utopia of 15-hour work weeks and intellectual self-improvement. It’s extremely timely, therefore, that two current art exhibitions in New York take nuanced, critical looks at the technological, political, and philosophical questioning AI demands.

Trevor Paglen’s exhibition A Study of Invisible Images at Metro Pictures augurs the similarities – and irreducible differences – between man and machine. The show looks at the image’s ontology at a time when Artificial Intelligence, emerging from the most recent “AI winter”, has seemingly achieved super-human performance in certain fields. Paglen’s show, by photographically visualizing datasets originally used to train character-recognition systems, questions how algorithms are taught. He presents MNIST, the foundational image-bank for AI research, as a grid, referencing the seriality of Sol Lewitt or Hanne Darboven. In a nod to their longing for the infinite, Paglen’s presentation makes manifest AI’s sheer hunger for training data.

Paglen’s work foregrounds the fact that a handful of companies are creating technology with immediate implications for the rest of us, ranging from privacy and automation-related job-loss to possible long-term existential threat. And they are doing this mostly in plain sight, benefitting from the passivity of citizens and regulators. Paglen matches luxurious materials – metal mounts and dye-sublimation prints – with the ostensible subject-matter, complex, abstract, and possibly boring to the layman; perhaps hinting at the complacent cupidity of the consumer-citizen.

Everywhere a subtle sense of the political: the image of the Martinique-born activist and philosopher Frantz Fanon, fuzzy and filtered through a face-recognition algorithm, stares at us, as if a ghost, from a future where humans no longer have technological mastery of their world. The portrait of Fanon, a doyen of post-colonial thought, is also a looming reminder of the inherent biases, unintentional perhaps but nevertheless consequential, that plague the training data-sets used in AI. Bias is obliquely referenced through archival photographs, obviously marked up by a neural network, of workers at U.S. military bases. The piece presents a carefully balanced cross-section by gender and race – a balance that arguably didn’t reflect the reality of military-industrial (or civilian) power structures when these photos were taken decades ago, and likely still doesn’t.

Trevor Paglen, “Four Clouds Scale Invariant Feature Transform; Maximally Stable Extremal Regions; Skimage Region Adjacency Graph; Watershed,” 2017. Image courtesy of Metro Pictures and the artist.

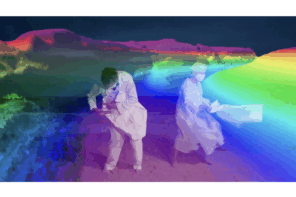

In another series, Paglen applies the image-recognition algorithms from military drones to four photographs of clouds taken over the Mexico-US border, where drones form a central part of the strategy of interdiction. In a talk he gave with AI ethicist Kate Crawford, Paglen discussed how clouds are actually the most confusing images for programs designed to identify targets: buildings, vehicles, and people. Repeatedly, he seeks to confound the computer, quixotically seeking human truths invisible to the machine. This is pure Gödel, refracted through poetry.

In the show’s most compelling and open-ended work, Paglen trained digital image-classification suites to recognize photographs corresponding to a number of abstract categories: examples include a section titled after Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, and one called “American Predators.” He then asked the AI to “hallucinate” or imagine new images that it thinks might correspond to these categories. Here Paglen transcends the rest of the show’s technological representation (however aesthetic and politically-charged), achieving a glimpse of the already-present future: the end of our monopoly on the creation and interpretation of images.

Trevor Paglen, “A Man (Corpus: The Humans) Adversarially Evolved Hallucination,” 2017. Image Courtesy Metro Pictures and the artist.

Elsewhere, ascending the ladder of abstraction, we find in Harry Dodge’s video Mysterious Fires (2016) a poignant exploration of the threats and anxieties inherent in AI. Entering the new Grand Army Collective space, we find a lurid green-screen backgrounding a dialogue between an AI and a senescent human. They are working through a script based on the Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom’s writings.

If Paglen interrogated the mechanisms of technology and revealed their biases and failures, Dodge makes the provisional and Promethean assumption that a self-conscious Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is actually achievable. According to Bostrom, AGI – essentially a conscious and hyper-capable AI – may pose an existential risk to humans, when and if such agents collectively become self-organizing, self-modifying, self-conscious, and self-replicating. At that point, he speculates that they might easily decide to do away with, or enslave, their human makers.

What struck me about Dodge’s video, more than the actual topic, was his formal and material approach. The mechanisms of video-making were laid bare, from the conspicuously unconvincing costumes, the off-screen directing voice, the repeated references to “script” and “cue” within the dialogue, and the nervous laughs and missteps of a rehearsal. Rogue surreal elements – a red hand, a confused-looking dog – subtly referenced films like Blade Runner while pointing to the capacity for irrationality, fundamental to the human condition.

Rather than inspiring terror at AI’s gathering power, the clunky production and odd, seemingly-accidental jars in the characters’ interaction actually recalled the frailty that Paglen explores. Dodge’s persistent and effective use of humor winked at one of the major outstanding sub-problems within the field: AI’s struggle to tell or understand jokes. These discordant notes (and others, such as one character’s struggles with American accents) became less evident as the video played out, rhyming with how neural networks actually learn, improving with each “training epoch.” In an echo of this year’s inescapable politics, the video felt as if we were watching a deeply-flawed child assume, and test the boundaries of, great power.

In a Brechtian formal gesture, Dodge repeatedly pierces the fourth wall, making demands. He seems to be asking a heavy question of us viewers: if we believe Bostrom, and AI is no less a societal risk than climate-change, nuclear holocaust, or gross inequality, why are our protests not commensurate to the threat? Perhaps we, like the apocryphal frog insensibly brought to a boil, blithely use Alexa, Google Photos, and Instagram, all of which, in turn, are used to train AIs that we know almost nothing about.

Urgent though this feels, the power of Dodge’s work comes from its balance and ambiguity. There is, media coverage notwithstanding, little consensus on whether AGI is actually imminent. In truth, perhaps the poles of “artificial” and “natural” represent a false distinction, conveniently created by humans to suit spectacle, anxiety, or ideology. Why should we be sanguine about artificial augmentation, whether prosthetic legs, cheekbones, or intra-cortical visual implants, yet somehow become hysterical when faced with an AI?

The two exhibitions seem brilliantly matched, offering different, and not necessarily mutually incompatible, viewpoints on AI. Paglen, looking to the near-term, seems to highlight the impotence, nay stupidity, of the algorithm, and warns of putting technology in the hands of malevolent governments and corporations. Dodge, more poetically, hints at how things might turn out if the technology actually works. He seems to ask: if the created beings are truly like us, and perhaps better than we, hardier, less defined by mortality, less constrained by egotism, what are the coordinates of our fear, our possible acceptance?

1 Comment