I see the use of multiple screens as a device to speed up the narrative flow in film, to conceptually give sequences (loops) momentary independence while serving the practical needs of the whole.

A Cold Day in Kyoto

It is a cold, rainy day at Rashomon Gate in medieval Kyoto. The structure is in ruins, and three men have found shelter under the hulking form. They sit talking about something that two of them have just witnessed: the trial of a suspected killer and rapist who killed a samurai, raped his wife, and stole the former’s horse and weapons. So begins Rashomon, Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece and arguably the most influential Japanese movie of all time.

The film is famous for the introduction of multiple narratives told in contradictory fashion from the points of view of each of the main protagonists: the rapist, the rape victim, the murdered man (communicating through a medium), and the wood-cutter, who narrates the story. Kurosawa sets it in minimalist, stark settings – the woods, the court yard, and the gate – and uses the court testimony device as a means of enabling each of his main actors to essentially play multiple roles, as each witness presents their testimony and describes the actions of the other players from their own perspective. In the end, the truth remains ambiguous, and the viewer’s desire to know exactly what happened is frustrated. As is often the case, there is no single viewpoint, just the expression of multiple, clashing “realities.”

This is What a Canadian Ghetto Looks Like

In his four-channel video installation entitled Watch My Back, Jorge Lozano features silent footage of four Latino youth (three male and one female) from Toronto ghettos, their naked backs turned to us. The screens act as a Greek chorus that presents four different yet similar experiences in the immigrant, disenfranchised youth living in Toronto’s public housing projects. Some of the characters relay their experience of being the “top dog” in jail, making the rules that others have to follow. Others speak of having to adhere to the rules while in prison. The installation is an extended metaphor for something the youth refer to, the necessity to “watch my back.” One of the males explains, “I never learned how to dance. Since I was young I had to protect myself and sit with my back to the wall.” We see the subjects’ backs in a stationary shot centered on the foreground, while the background images are in constant flux. They feature close-ups of the “delinquents’” crude prison tattoos (what are clichéd images that one would expect to see painted on Hollywood movie thugs) bearing legends like “Only God Can Judge,” “One Life to Live,” and “Mi Vida Loca”; with images of dice, pit bulls, and guns, interpolated with shots from their rooms, where posters of pinup girls, Al Pacino in Scarface, and the gangster Al Capone hang on the wall. I wonder at such an extensive display of corny Latino stereotypes, but then the paradoxical reality of these surroundings sets in: as the camera pans away from one of the teen’s rooms, we see that his home is clean, tidy, and suburban, and we see a young boy (his brother, perhaps) watching a horror movie on television from the family couch. The most disturbing aspect of the installation, aside from the harshness and brutality these people endure, is the element of the female teenager. Behind her is the Toronto neighborhood of Jamestown; the subtitles tell us that she doesn’t drink or do drugs, but she still had to spend time in jail. Her naked upper body with its back to the viewer implies that she is nude, and facing the children riding their bikes, trash dumpsters, clothing lines, and passers-by who appear oblivious to her presence, like in a bad dream.

The four subjects offer solutions for the social problems that assail them, but in the end these solutions are reductive. The cause for all their ills is in turns identified as the white man, society, and the police. Or, as the young woman’s subtitle reads: “We have no way of expressing ourselves because there is no money for it.” The answer to this dilemma is that there is no permanent solution. And Lozano’s plasma-screen chorus constantly makes this clear.

Death Match

The young man is slumped on his bed. He wears an ‘80s-style quarter-sleeve heavy metal band T-shirt and jean jacket. His long, stringy hair is nicely combed; his mouth half open, as if he is about to say something. He lies on top of a cheap-looking comforter. The wall behind him is a crummy wooden paneling that was never varnished or is simply dirty. A large butcher knife lies at the foot of the bed. There is a circular black stain around the knife’s handle. The tip of the blade intersects the body of a shotgun. The young man’s extended index finger points in the same direction as the gun’s nozzle – towards his legs, somewhere outside of the picture plane. His eye is open, and his brain has fallen through a hole in his frontal lobe, and rolled onto the bed.

This is the front cover of the bootleg album Dawn of The Black Hearts by Norwegian Metal band Mayhem. It’s a picture of their lead singer, Dead (A.K.A. Per Yngve Ohlin).

The album was originally released in 1995 on vinyl in an edition of 300 copies on the Colombian metal label Warmaster Records, owned and operated by Colombian natural Mauricio “Bull Metal” Montoya. These are the original liner notes:

We have no vocalist anymore! Dead killed himself two weeks ago! It was really brutal, first he cut open all his arteries in the wrists, and then he had blown off his brain with a shotgun. I found him and it looked fucking grim. The upper half of his head was all over the room, and the lower part of the brain had fallen out of the rest of the head and down on the bed. I of course grabbed my camera immediately and made some photos, we’ll use them in the next Mayhem LP.

I and Hellhammer were so lucky that we found two big pieces of his skull and we have hung (them) on necklaces as a memory.

Dead killed himself because he lived only for the true old Black Metal scene and life-style. It means black clothes, spikes, crosses, and so on. You know, bands like old Hellhammer, Bathory and so on … but today there are only children in jogging suits and skateboards and hardcore moral ideals. They try to look as normal as possible. This has nothing to do with Black. These stupid people must fear Black Metal! But instead they love shitty bands like Deicide, Benediction, Napalm Death, Sepultura, and all that shit!!

Dead died for this cause and now I have declared war!!

I’m angry, but at the same time I have to admit that it was interesting to be able to examine a human brain in rigor mortis. Death to false Black Metal or Death Metal!! Also to the trendy hardcore People … aarrgghh!!

— Euronymous … April, 1991. Two weeks after Dead’s suicide. [Euronymous (Øystein Aarseth) liner notes for Mayhem’s Dawn of The Black Hearts Warmaster Records, 1995]

Lozano’s Death Match (2010) opens with an onscreen text describing how his nephew suffers from Renal insufficiency or chronic renal failure, in which the kidneys fail to adequately filter toxins and waste products from the blood. They are atrophied, inhibiting him from being able to urinate. The young man points to his hand and tells the viewer in horrifying detail how five of the veins were shut close, and he points to the part on his wrist where they inserted a prosthesis to take in the needles. He shows the scars on his abdomen where they inserted catheters. He stands naked, his small frame against a wall, his arms are swollen, he is small and frail. His blood must be cleansed three times a week or he will die. We see a shot of his arm connected to the machine, three different tubes running in and out of his arm; the tubes are red because of the blood. He talks about seeing his friends die, some from cardiac arrest, some from stroke, while they were hooked to the machine. “We look at death in a different way than normal people. For us death is something natural, something very beautiful, something that comes to some earlier, and others later, but we must accept and live with it. Because of all the changes in the machine you could die, suddenly, falling into a deep sleep from which you will never wake up.” As the screen blacks out, a song by Rogelio’s band Death Match comes on, recorded in the same Lo Fi, basement-ghetto-blaster production style as that of a Norwegian Black Metal recording.

Napoleon 67

The young Napoleon Bonaparte is playing in the snow with other children. A snowball fight ensues, and Petit Napoléon goes on to direct his young cohorts, military campaign-style, to victory. It is the opening of Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927). An epic silent French film that tells the story of the rise of Emperor Napoleon I of France. Considered to be among the longest films ever made, Napoleon clocks in at just under six hours. Gance was planning to make six films about Napoleon (this was to be the first), but the budget was simply too prohibitive. A large number of scenes were hand-tinted, and many were shot using an innovative hand-held style. But the most impressive achievement of Gance’s Napoléon is the third reel, which was to be projected, triptych style, by means of a triple projection, or Polyvision, on three separate screens, creating a sense of multiple, yet simultaneous points of view.

Unfortunately, much like his Austrian counterpart, Erich Von Stroheim, Abel Gance was dealt a severe blow when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the rights to his film, considerably cut it down in length, and discarded the Polyvision elements.

It wasn’t until the film’s restoration and subsequent showings in Britain and America in the 1980s that the full impact of Gance’s genius, and the brilliance of his film, were recognized and reinstated to an esteemed position within the canon of world cinema.

The year 1967 was a great one for Montreal, in large part because Expo ‘67 was considered to be the most successful World’s Fair to date. At the center of the Expo was In the Labyrinth, a film by Roman Kroitor, Colin Low, and Hugh O’Connor. It was a never-before-seen multi-screen presentation that used 35mm and 70mm films projected simultaneously on multiple screens. The forerunner of today’s IMAX format, In the Labyrinth broke the picture plane into a single image or a tiled mosaic of images that at times coalesced or contrasted against each other to create lateral connections between images, expressing loss, pain, and transcendence while suggesting that all human beings are interrelated, regardless of race, sex, or creed. Years later, Kroitor was credited by George Lucas as being the person who created the concept of “The Force” which features so prominently in the Star Wars narrative.

I Am A Multiple Screen: An Interview with Jorge Lozano

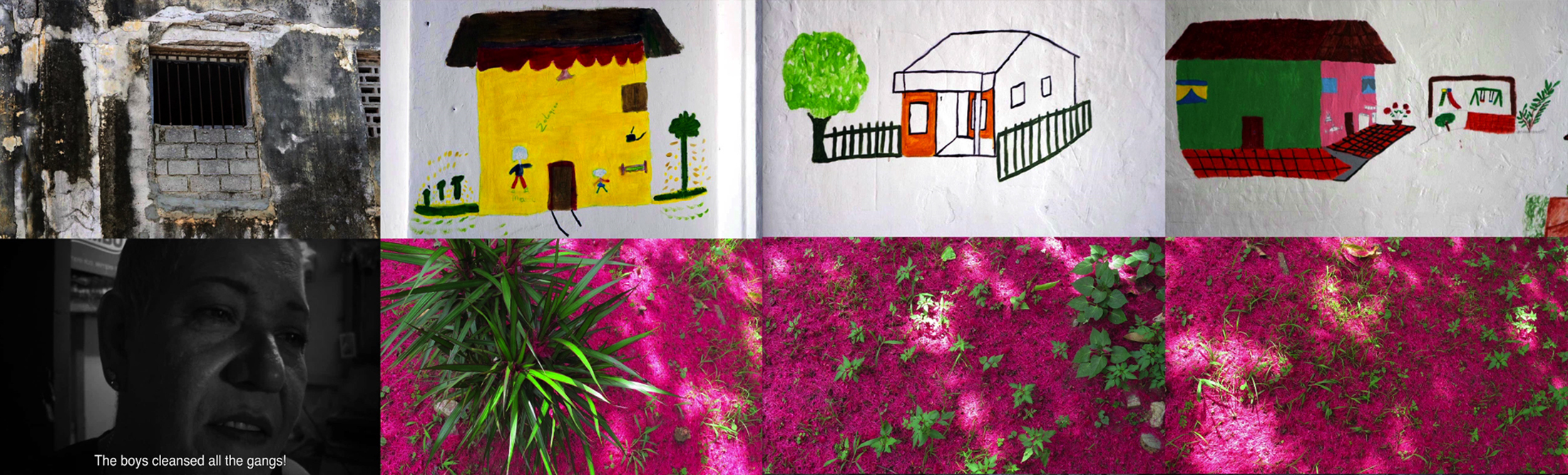

Yes, you can say that MOVING STILL_still life (on view at The Ryerson Image Centre in late 2015) includes sampling and remixing and appropriation indirectly. But it’s also an experiment; I call it a “collaboratory.” The work is the result of a series of self-representation video workshops, mostly based on helping the youth to conceptualize ideas into visual images and to produce an artistic work of their own. The workshops took place in different neighborhoods in Cali, but mostly in Siloe and the marginalized, culturally rich area made up of different neighborhoods. After working there for many years I decided to produce a work in 2010. With MOVING STILL_still life I wanted to recreate the simultaneous multiple perspectives and the fragmented flow of events and visual information, which is the way I feel when I am in that place. This is why I designed it as an installation of eight monitors. I have been showing one single screen because it is difficult to show installations. MOVING STILL_still life investigates how the environment affects the emotions and behavior of individuals, and how these individuals can perceive, think, and alter the coordinates of their world in order to negotiate with other youth living in the area but who belong to a different group. It captures both their conscious and unconscious responses to cultural, economic, and political constraints and inequities.

The reason that I included clips from the youths’ own works is because I realized that when they use fictionalized violence, they do it as a way of documenting their own lives. Fiction is a way for them to document their stories, resolve problems, and propose solutions. It is a way to redeem themselves; to position themselves within the violence while finding ways to survive it. It is a game where you don’t die, but if you do die, it is because you went the wrong way. And most of them have been living their lives “the wrong way,” and doing these works within the workshops helps them to better see themselves and move along creatively. I interviewed the youth, and they in turn interviewed others. The work became a mesh of their own views and mine. I would say that MOVING STILL_still life is the sum of fragmented individual experiences that create multiple narratives.

There are six interviewees in the installation. And they were included because I had been working and in contact with them for the last six years. I still go there and bring them equipment and facilitate mini workshops. All of them are working actively in video and they are starting to make money, which is what they need the most. One person, the woman in jail, was interviewed in her cell, and I included her because she represents the paramilitary armed approach to “social cleansing,” which consists of summarily executing anyone whom they consider to be an enemy: queers, gang members, leftists, etc. The paramilitary are worse than a horror movie.

Participating in the workshops had the greatest impact on their lives. They took a 360° turn. Most of them are working professionally. Black has become an editor and has made several documentaries. He is currently finishing a feature film script. Ronald produces videos and teaches workshops. Some have hip hop groups and make their own videos. In regards to MOVING STILL_still life, it is a personal film mostly about my own perceptions. The result has been constructive; they worked with me as colleagues and when they saw the work they realized that they have the potential to make documentaries differently, in a more experimental vein. They also realize that they have the possibility of doing their own documentaries, from their own perspective, from the inside, and they are planning to do so. My work is more phenomenological. It is about me going trough, a psychogegraphic experience.

The interviews are direct and obviously aimed to destabilize the power dynamics. In one way the interviews that I conducted were easier. I know the interviewees and I challenged them. But when the youth did theirs, they had to be more careful; they had to know what and how to ask, and they had to be well known and trusted by the interviewees, as in the case of Meikel, the kid with guns, and the kids in the Los Wonders gang. Two weeks after the interview Maikel killed another boy and he is now in hiding somewhere. The children’s gang Los Wonders are posers – to be in a gang is about posing – and yes, they are mocking themselves. However, they do kill and get killed, and they are so young, nice, and somehow innocent.

People are somehow culturally specific, especially if you’ve grown up and spent all your life in the same area, framed by the same social interactions and events. In Canada I made a work called Watch My Back. I worked with Latin Youth in Toronto who live in the ghetto, and whom I have known through the workshops that I facilitate. Ironically, the youth in Toronto have been in jail many times; they have been imprisoned mostly for ridiculous reasons. And the ones in Colombia, where there is more violence and death, never mention the police. We have a country where social control and incarceration is very strong and it is mostly exercised against the more vulnerable sectors of the population who are economically and politically disadvantaged, and then you have another country, Colombia, where there is impunity and corruption eating away at any opportunity for marginalized youth and poor people in general. In both cases the youth are born or landed in the mist of violence and they have many things in common: talent and creativity and little resources to apply it, however they do it if you help.

Dance and music are strong in Colombia. After the workshops, the youths’ ability to make videos is now a reality, and joining a dance, music group, or making “films” gives them status and respect in the eyes of the other kids, especially the gangs … remember they have to be in gangs. It is a survival mechanism, but survival mechanisms are not fixed; they can be culturally based, and if you are part of a cultural group somehow the neighborhood admires you, and if you are good they all see themselves reflected in you.

I avoid the hierarchical ways of teaching. In the workshops, working with Guillermina Buzio in Colombia and Alejandra Gelis in Colombia, Panama, and Toronto, we always called ourselves facilitators and colleagues. Right from the start we made clear that we were not teachers, parents, or psychologists and that they were there to learn mostly on their own initiative and to produce a good work. And at the end we all learned. We learned about them: what they know how they see think and feel; and they learned the same about us. This is empowering for all of us and at the end of the workshops we are all changed.

When working with the youth in Colombia, I am always protected by transparency and by not going there with double intentions. I am from a popular neighborhood and I know how to communicate and they can see through me. In those neighborhoods, when you are working with their youth in video (or “film” as they call it), everyone wants to be a part of it. Everyone there wants to be an actor, therefore everyone is friendly. Even the worst ones want to be famous. You know those people make films all the time and now they are starting to record with their cellphones, because they want to be known in the virtual world. It doesn’t matter what the content of the film is or what their actions are within it. The time frame is also important. If you stay too long, the novelty wears off and you become a part of the landscape. You are more visible because of your equipment and you know what can happen. Also when I am there, I forget about dangers or dying, all that stuff. If I get killed, there is nothing that I can do. I won’t have to pay rent anymore.

Everything in the piece is made up. The work went trough the selection of editing. However what was left represents a reality. The reality of their fictions in the segments of their work that was used, the reality of their lives and the reality of the neighborhoods with their celebrations and violence, and celebration of their own violence and the celebrations of their loving and peaceful moments. When it rains there you get wet; and when it’s hot, it is really hot … it is real.

Multiple screens have always been here, but now TVs and projectors are more accessible so it is easier to work with them. My interest in creating installations using multiple screens has to do with several influences: a film that I saw many years ago in the ‘80s at the NOVA convention in NYC that used a diptych format featured a very powerful display of the same images shot twice from different angles; my reading about quantum physics and the superposition effect where two electrons can be in two different places at the same time; and also my fragmented polymorphic and polysexual way of looking at the world. Multiple screens is me; I am a multiple screen.

CODA

When it was released in 1950, Rashomon was not well-received in Japan. When it was suggested that it be included in the Venice film festival, Japanese authorities were reluctant to include it. They didn’t see it as representative of their national cinema. When the film went on to win the critic’s award and the Golden Lion Award at the same festival, Japanese critics were baffled. Yet the influence of Rashomon has permeated world culture and the device it introduced became standard fare in such forms as American Sit-Coms, and has even entered the realm of psychology, in the form of Karl G. Heider’s Rashomon Effect.

However, unlike its Western manifestations, in which one of the subjective truths achieves hegemony of significance offering an ultimate resolution to the differing narratives, Rashomon obstinately refuses to do so. There is simply no resolution. There’s only the constant shifting of meanings that can be reinterpreted but never resolved, like Jorge Lozano’s plasma choruses.