In 2005, at the Canadian Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, Indigenous artist Rebecca Belmore projected a video installation called Fountain onto a wall of rushing water. The piece played with the elements, portraying the artist in a physical struggle with water, which ultimately morphed into a substance reminiscent of blood. Straddling an ambiguous zone between metaphor for creation and apocalyptic prophecy, Fountain presented nature as infinitely bound-up with, and deeply polluted by, humanity. In the catalogue accompanying her Biennale exhibition, the curator described Belmore as “an Anishinabe living in the continuously colonial space of the Americas.” This biographical distinction is crucial to understanding Belmore’s relationship to the land in her art practice.

This is one of several contemporary artists whose work agitates against the legacy of Land Art – a movement widely known for its boys’ club bias and large-scale environmental disruption under the guise of ecological awareness. Belmore stands out in the greater context of the Land Art movement, addressing trauma and memory from the embodied position of someone whose relationship to the land has been severed. Her overtly political restructuring of Land Art tactics maintains a certain proximity to earlier generations of feminist Land Artists. By contrast, others working in the movement, like Feminist Land Art Retreat (FLAR), seem to interrogate these politics in more indirect, ambivalent ways.

FLAR, “Treatment 6-7,” 2016. Billboard, installation view, Kunsthaus Bregrenz Billboards. All images copyright the artist.

A decade after Belmore’s Biennale installation, FLAR deals with similar issues in a sardonic video work titled Heavy Flow (2015), which pairs imagery of an erupting volcano with grandiose words like “explosive” and “timeless” (words that appeared on a poster for the video). The piece appears to be wryly critical of the whole Land Art tradition: both the 1970s movement stemming from the all-male Earth Art exhibition (1969), and its feminist counter-examples. The invocation of flowing lava (or, menstrual blood) as a natural, female element mocks the use of dated, binary, second-wave tropes. Even FLAR’s name suggests a performative, tongue-in-cheek reflection: not entirely dismissive, but rather seeking to update the practice’s core tenets. Perhaps this represents an overdetermination of FLAR’s politics, which has elsewhere been described as open to negotiation, providing “no answers.” Nevertheless, the proposition of a feminist Land Art retreat is a performative gesture both strangely appealing and, when you’re caught in the realization that it might be a joke at your expense, profoundly irritating.

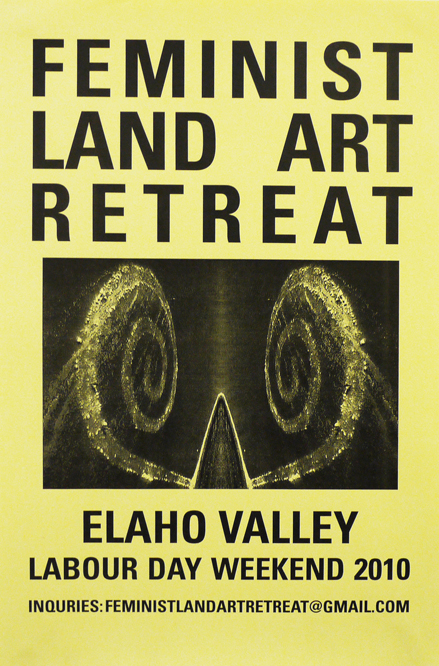

FLAR began in 2010 with a simple poster campaign seemingly advertising one such feminist retreat in Elaho Valley, British Columbia. The ambiguity of its relationship to Land Art seems to reside in this had-to-be-there moment. Whether born from a genuine desire to host the gathering, or intended as a caricaturing of feminist separatism, self-communion, and retreat; the poster – printed on cheap paper with a doubled image of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) recomposed to look like a spiral IUD – anchored the body of work that would follow.

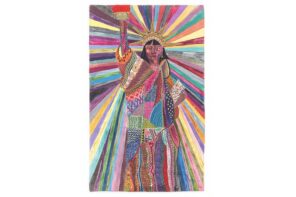

The project continued to grow. Annual posters advertising the FLAR began to pop up in Vancouver art spaces and included reproduced black-and-white or sepia imagery from textbook accounts of feminist Land Art: naked women sitting in circles, or contorted in ritual positions in desert settings (2012-13). The pair’s work is partly performance and installation-based, but largely appears in the form of graphic promotional materials, as a series of posters and billboards. Representing these images in decidedly retro or DIY aesthetics – turning this once-rebellious visual language on itself – FLAR highlights a growing critical irreverence for Land Art in general, and its abhorrent gender dynamics.

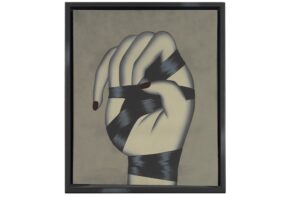

In parallel to this veiled critical output, the acronym gradually became a brand; temporary tattoos, T-shirts, and even a limited-edition series of FLAR stockings appeared alongside exhibitions in Canada and Europe. A series of billboards in public space, presented as part of FLAR’s 2016 exhibition LAST RESORT at Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria, reproduce devices from Land Art (again, Smithson’s Jetty looms large), this time on the mud-caked bodies of spa clientele. As in many ‘70s feminist Land Art works, such as Ana Mendieta’s famous Silueta series (1973-8), the body – a muddy calf squished between two imposing hands or a shapely back – becomes the raw material for earthworks. But FLAR’s updated versions, presented as glorified ad campaigns, bring this body-nature relationship into conversation with capitalist visual language and the discourse of self-care as consumer product.

These gestures emphasize the commodification and marketability of feminism today. FLAR, appearing in the form of various products and advertisements, might in fact profit from the media frenzy to “unearth” feminist land artists (or “forgotten” women artists in general), who were buried under the cultural weight of their male counterparts. Alternatively, they may create the necessary critical distance to recognize this absurd appropriation. Intentions matter a lot here.

Yet, FLAR’s body of work does not convey an easy political stance – at times feeling like a mockery of feminist Land Art, and at others an earnest homage. Their performance Throw Your Voice (2015) at Dan Graham’s pavilion, outside K21 in Düsseldorf, is an example of their sometimes-sincerity. It saw FLAR organize the planting of an apple tree with visitors, while a recording of Graham’s Performance/Audience/Mirror, read by the duo’s female relatives, played inside the pavilion. The ambiguity between reverence and ridicule places FLAR’s critique outside of established genres.

A complex grappling with the fraught history of Land Art connects Belmore’s intersectional feminism to FLAR’s far less categorizable work. Running through them is a strong desire to reclaim the anxieties and strategies of feminist Land Art. They push to address more structural problems, encompassing but exceeding the purview of gender inequality: addressing themselves to historical trauma and capitalist appropriation. FLAR’s refusal of rigid distinctions – its propositional politics – affirm a conceptually nascent and vastly heterogeneous “fourth wave” feminism.

“In the catalogue accompanying her Biennale exhibition, the curator described Belmore as ‘an Anishinabe living in the continuously colonial space of the Americas.'”

In Alison Hugill’s essay, from which the above quote is taken, the author made a conscious decision to not mention the name of the curator who Belmore worked with to bring her Fountain to Venice?

An art retreat is an excellent opportunity to experience different painting styles and teachings and gain knowledge that will last a lifetime.

I like your photos, and the post as well. Thanks for sharing.