Harald Szeemann organized a show called Friends and Their Friends in 1969, his last year as chief curator at the Kunsthalle Bern. Selected artists were told to invite their friends, and Dieter Roth asked Dorothy Iannone, his friend and lover, to install work alongside his. Iannone’s four-decade-old book, Story of Bern (1974), chronicles the show. A few pages in, Szeemann places brown squares of tape over the exposed genitals in Iannone’s drawings (her figures’ privates always hang out). Later, Szeemann wavers over the tape censorship; bureaucrats and artists weigh in, and then, right before the opening, he removes all of Iannone’s work.

Roth asks, “Whom were you afraid of Harry?”

“No one!” says Szeemann, “the Kunsthalle was to receive a great deal of money.”

“So you were afraid of money,” concludes Roth.

“No of course not,” retorts Szeemann. Near the book’s end, he stands before Roth and Iannone and declares: “I have resigned from the Kunsthalle.”

Story of Bern masterfully depicts the tension between Szeeman’s desire for experiment and his instinct toward self-preservation. “But we had to think of Harald’s position!” his colleagues repeatedly say.

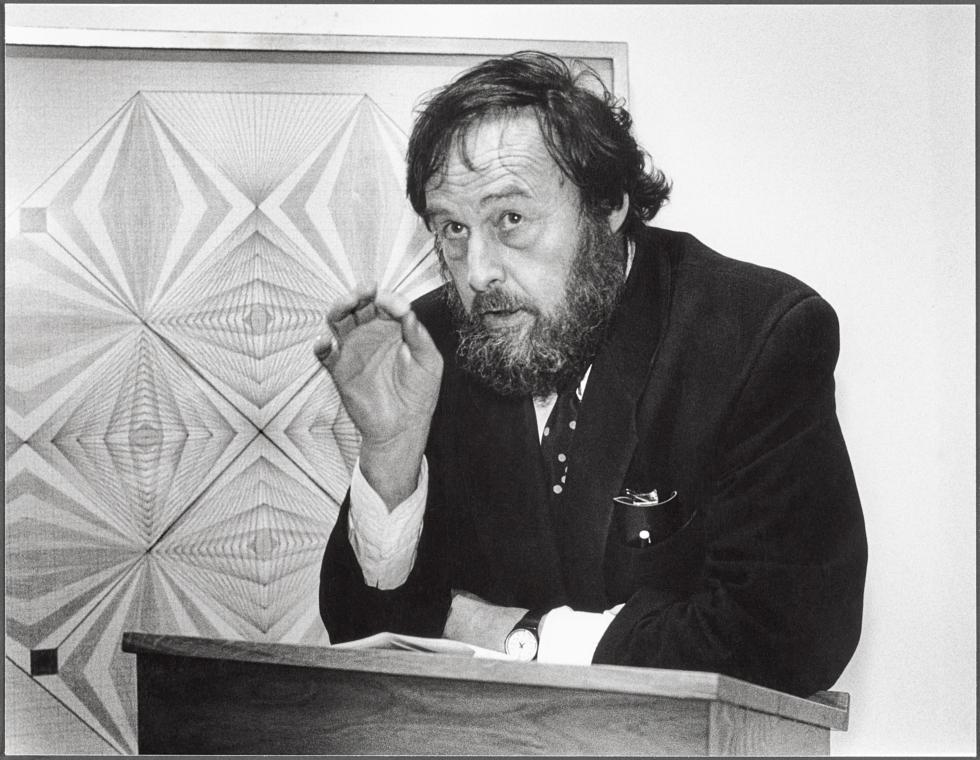

Harald Szeemann lecturing in front of “Werk Nr. 003,” (undated) by Emma Kunz. Artwork courtesy Emma Kunz Zentrum. © Anton C. Meier.

Two Los Angeles exhibitions demonstrate how well the curator ultimately preserved his position. One, downtown at the ICA, recreates Szeemann’s crowded 1974 apartment show, Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us, while Museum of Obsessions at The Getty Research Institute in Brentwood pays tribute to Szeemann’s lifelong accumulation of interests and artifacts. Both exist because the Getty recently acquired the curator’s massive, 1500-linear-foot archive. Each includes remarkable minutiae. Indeed, these exhibitions chronicle Szeemann’s preservation of his objects and ambitions so well that they become about having and achieving, and the ideas and artists he worked with take a back seat to his cult of personality.

In the catalogue for Museum of Obsessions, curator Glenn Phillips recalls his first visit to the Szeemann’s archive: he “had kept everything that came his way […]. The physical chaos around us was the relic, left largely intact, of an active office led by a voracious intellect.” Curators and critics often use words like “voracious” to describe Szeemann. “He invented the curator as art star, a globe-trotting, deal-making, usually male impresario,” wrote Roberta Smith when he died in 2005. Curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist, himself a male globetrotter, revered Szeemann and writes of him often. “People by this point knew that Szeemann was a great man,” said PS1 founder Alanna Heiss, speaking tongue-in-cheek about one of his final shows at a 2011 Getty symposium. Royals attended his openings by the end. In contrast, Lucy Lippard, less of a self-promoter, and Seth Siegelaub, who dropped out after conceptualism became commodified, receive rarer credit for preceding Szeemann with their own voracious exhibitions.

The Getty show, dominated by seductive vitrines, starts back when Szeemann still worked at Kunsthalle Bern, and includes plans and documentation of his now-legendary 1969 show, Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. An accidental studio visit with Jan Dibbets – Szeemann intended to visit Dibbets’s employer, a painter – sowed the seeds for Attitudes. Neon glowed from the surface of one table in Dibbets’s studio, and grass grew on the surface of another. The curator decided to do a show full of seemingly spontaneous gestures like these, and the Philip Morris Company funded his artist-finding missions across Europe and the U.S. At the Getty, a letter from Robert Morris explains how to collect a pile of combustible materials in the galleries and burn it on closing day, and installation images capture a gratifying freedom: sculptures laying on the floor, obstructing motion, skin-like fabric draping down from hooks, nothing framed. All this baffled certain vocal audience members. A letter from the curator’s mother, displayed in a vitrine, asks him to stop these “gags.” Local cartoonists depicted the curator picking through a junk shop, planning his next show. The Kunsthalle’s exhibition committee decided that from then on they needed to sign off on the museum’s programming. The Friends show censorship controversy followed, and then 36-year-old Szeemann left after eight years in Bern.

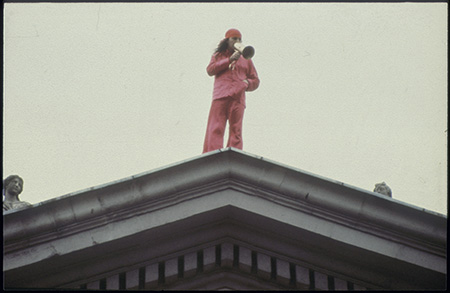

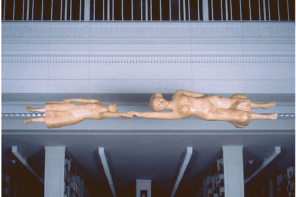

Szeemann’s first major post-Bern undertaking, documenta 5 in Kassel, Germany, included many of the same (mostly male) artists from Attitudes. He wanted to orchestrate a 100-day art “event,” not a temporary museum, as he believed past iterations of documenta had been. A black-and-white photograph at the Getty shows James Lee Byars standing on the roof of the 18th-century Fridericianum, calling out common German first names: a mundane action as spectacle. In another photo, a balloon by architecture firm Haus-Rucker-Co expands out from a window, with a tree and ladder enclosed inside. But becoming a free agent did not liberate Szeemann from controversy. A trio of letters in one vitrine tells the story of a confusing scandal that preceded the show’s opening. A letter purportedly from Szeemann, about the relative absence of female artists, reads: “The whores were at it again. […] I give the orders. Women should make soup, that’s all.” Lucy Lippard, who actually had made supper for Szeemann the year before and gave him a list of female artists to consider, angrily responded: “We gave you a short list knowing perfectly well that you would not visit more than a token number. You failed to do even that.” Jon Hendricks and John Toche of the Guerilla Art Action Group wrote, “WE REFUSE TO ACCEPT THE VICIOUS MENTAL ATTITUDES OF THIS SEXIST NATIONALISTIC LETTER.” Then, a few weeks later, Hendricks and Toche admitted to forging the original letter from Szeemann to “bring attention to the sexism of [documenta 5’s] organizers.” Eventually, Szeemann sent Lippard a passive-aggressive reply: “I beg your pardon for all the time you had to spend in my company.” After documenta, the curator decided to retreat. The show “had been brutal,” he told Obrist in 1995.

Haus-Rucker-Co (Laurids Ortner, Manfred Ortner, Klaus Pinter, and Günter Zamp Kelp), “Oase No. 7 (Oasis No. 7),” 1972. Photo: Balthasar Burkhard.

In the years that followed, Szeemann worked on a show entitled Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us, which is currently recreated at the ICA. His subject was his immigrant hairdresser grandfather, Etienne, and he held the exhibition in his own apartment, displaying his grandparents’ possessions by theme. Images of the original opening party have a smoky, casually-chic look – guests sitting and leaning on the furniture, cigarettes in hand. The attitudes of attendees appear more precious than the environment. At the ICA, however, lockers outside the apartment-within-the-gallery hold all bags, coats, and purses, so that nothing brushes up against the artifacts, which have grown in value over time (though the curators did some thrifting themselves to approximate missing things). Notes and family documents in the entryway betray family tensions – not everyone liked Etienne and not everyone liked Harald. The recreation of the grandfather’s bedroom and salon are immaculate: antique curlers, a wig Etienne designed, quaint wallpaper, the rooms tastefully overfull. It’s a feat, pulled off with the help of detail-oriented installers. Yet the show feels like it’s mainly about the curator: his grandfather functions as a deceased and thus cooperative conduit.

Etienne wasn’t the only one upstaged. Carl Andre wrote Szeemann in advance of documenta, “Do you have an art section? – that’s where I belong,” implying that the curator’s other interests often clouded his attention to art. Daniel Buren complained that “more and more the subject of an exhibition tends [to be] […] the exhibition as a work of art.” The Getty exhibition, to its credit, includes criticism like this. Artist George Brecht wrote to Szeemann in frustration in 1969, “You should work with artists before you conceive a show and not after. Are you another egotist? We have enough of those in art, and in meta-art.” Méret Oppenheim wrote him in 1975, after he included her in The Bachelor Machines, a traveling exhibition centered on Duchamp. He placed her work in a section of the show called “Femme Fatale.” “We should have talked about it more,” said Oppenheim. “A ‘femme fatale’ is a woman who is totally oriented to men. […] This is something that never interested me at all.” Artists consistently challenged the curator’s auteur-like methodology, their objections now texturing his story.

In 1972, Szeemann began the project that would become his archive, the Museum of Obsessions (from which the Getty show takes its title). He told Obrist in 1995, “I invented this museum, which existed inside my head.” He “combined works by artists who create symbols that will survive them,” he said, with artists who had “primary obsessions, whose lives are organized around their obsessions.” As he would repeat over the years, Szeemann wanted to abolish the institutional barrier between high and outsider art. The leveling-out that resulted is the most compelling element of the Getty installation: all of Szeemann’s interests, whether Duchamp or Swiss outsider artist Heinrich Anton Müller, warrant equal treatment. His preoccupation with the communes in Monte Verita, a hill originally established as a “vegetarian colony” in 1901, play a central role. In 1978, he exhibited documents from the commune’s history in a show called The Breasts of Truth. A striking photo of performers, half of them nude and all posed by a lake, hangs at the Getty. All were fascinating in their own right – one performer pictured, Suzanne Perrottet, innovated dance education in Zurich – but here they primarily illustrate Szeemann’s breadth.

The message of the exhibition seems to be that he who preserves, manages, and trumpets his own legacy in gratuitous detail ensures his “position.” Other figures championed the same artists Szeemann did. Certainly, it would be helpful if gallerist Eugenia Butler kept thorough records of every impulse, or if Lippard’s archive at the Smithsonian (53.6 linear feet in size), or Siegelaub’s at MoMA (15.5 feet), better approximated that of Szeemann’s (1500 linear feet). These curators relate differently to posterity, and it can be hard, amidst so much material, to remember that Szeemann’s was just one approach to championing the experimental. At the exit to the Getty exhibition stands the only sculpture by the curator included in the show. A tall mound of luggage tags resembling a Christmas tree, it reminds us that history is still too often written by those convinced that their every movement matters.