Joseph Tisiga is an emerging artist of a particular stripe. He is young (born in 1984), and very successful: he was nominated as a finalist in the RBC Painting Competition (2009); long-listed for the Sobey Art Award (2011); and included in the contested but establishing 2011 exhibition, Oh, Canada, first shown at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts. But as an artist straddling two “nation states” – born in Edmonton, Alberta, and moving between rural and urban centers before, as a late teen, voluntarily engaging in his native Kaska Dene Nation and living, since then, in Whitehorse, Yukon – Tisiga has forged a difficult bridge between North and South, and has had to reconcile himself to the discrepancies (or “lottery,” or “unfairness,” as he describes it) of being a rare exception among his cohort: landing a platform for his work in the South, while living and working in the North.

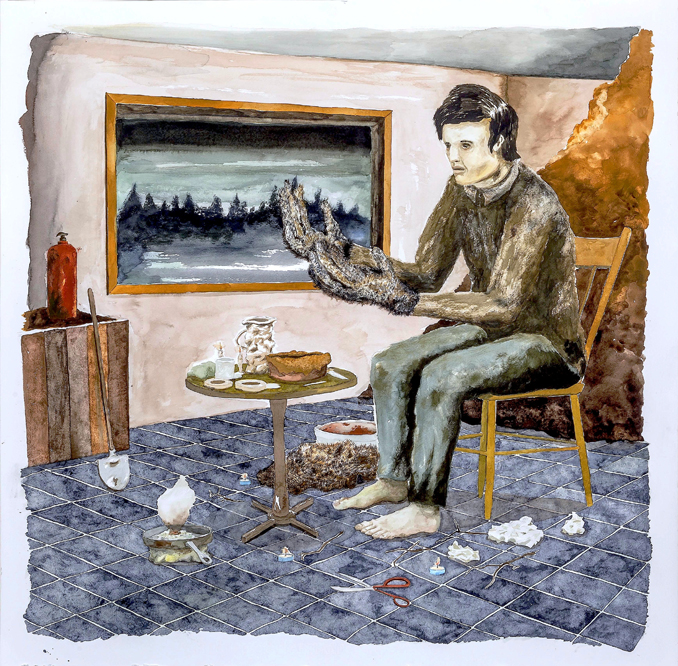

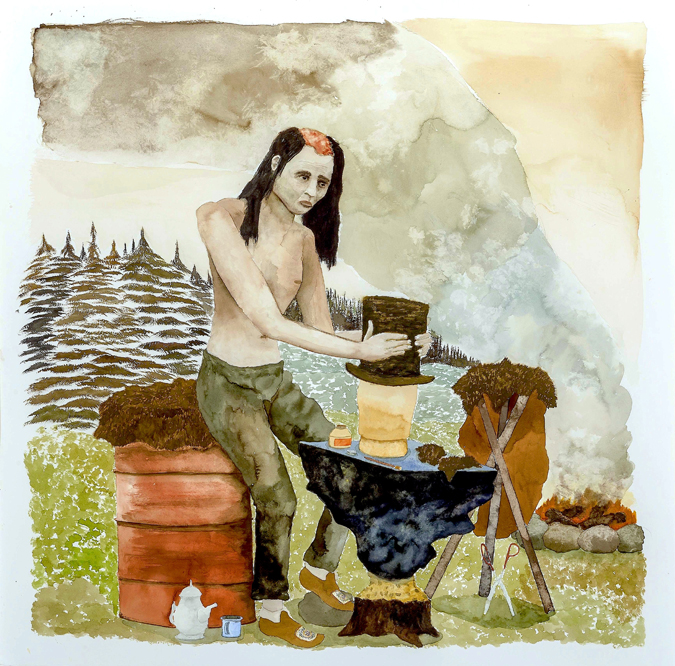

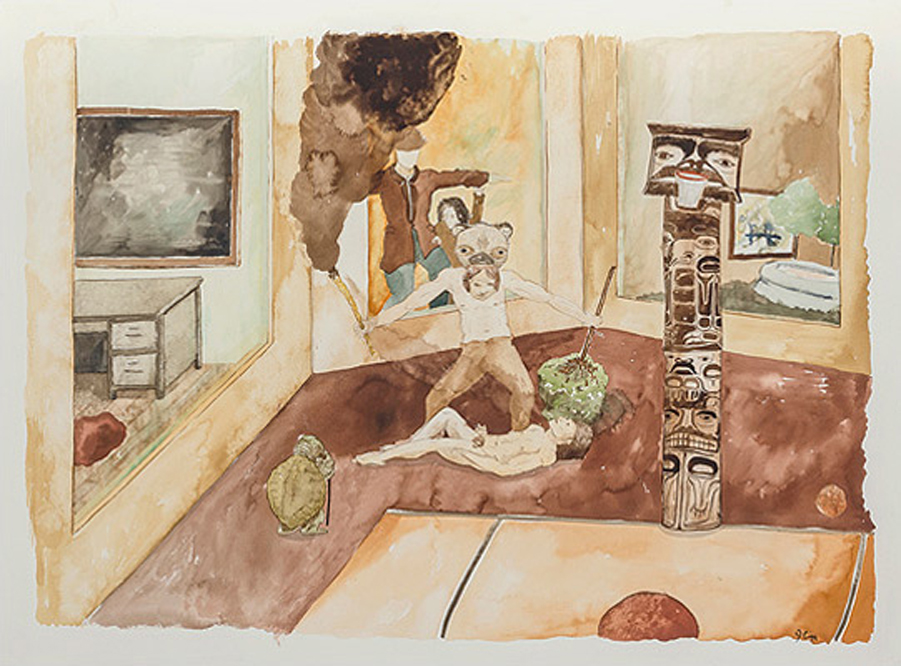

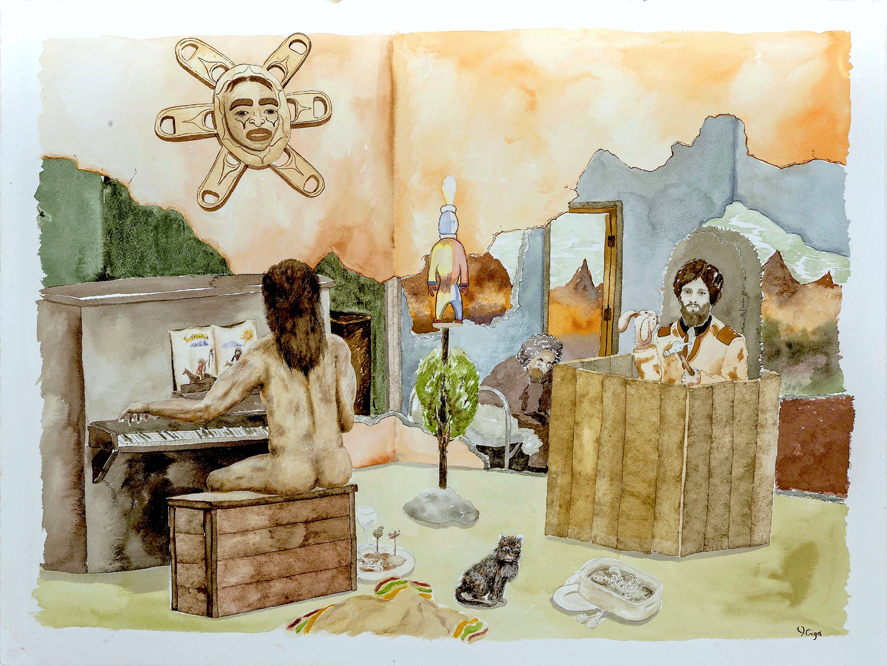

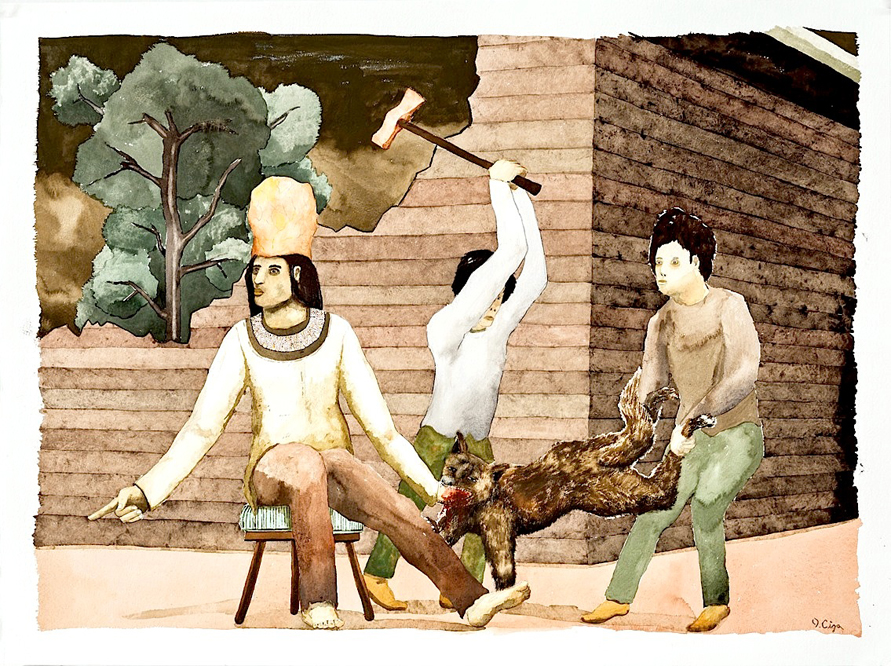

Tisiga came to my attention in the Fall of 2014 with a narratively electric and conceptually cunning solo exhibition at Diaz Contemporary (a Toronto gallerist who continues to surprise me with his expansions; this is, arguably, Benjamin Diaz’s first truly figurative artist after a decade of featuring largely abstract, minimalist, and conceptually-bent artists). I keened to review the exhibition but felt shorthanded; I wasn’t confident enough in my entry. Were Tisiga’s descriptive, stagey paintings of slightly perverted, certainly cryptic scenes illustrative of First Nations lore? Or were they – as in the work of Kent Monkman and Duane Linklater – purposeful subversions of that very material, content bearing signifiers that I felt anxious to read without directives? I opted for an interview. But not just because I felt his work to be suggestively inscrutable; I wanted to query his unlikely success as an emerging artist bridging a pronounced divide. Over the course of two interviews, and the better part of a year, I asked Tisiga about his comfort level in achieving a heightened status; his anxiety about surpassing his colleagues in the Yukon; and his advice for exhibiting intuitions on how to gap the geographical and cultural divide for which he’s only recently achieved a bridge.

There’s a bold opening pronouncement in Ben Portis’s review of your Fall 2014 solo show at Diaz Contemporary, where he calls it “a full-fledged, true national debut.” How did that sit with you?

I don’t know if that’s how it would have been generally received, but for me, the reality of it was that it was my first solo exhibition anywhere out of the Yukon – which, in that sense, I guess it would be a national debut. [Laughs]

I realize there’s an ego-centricity in Torontonians framing their exhibitions as representing “the nation.” But I’m curious about the transition from the Yukon to a major urban and cultural center, and a commercial gallery, at that; I’m wondering how you perceived that shift. Were you aware that you were breaking through to a new level of exposure? Was that a complicated realization, given that it was happening in the south after so much exposure in the north?

I don’t know that I think about it like that. For me it was really great to work with a gallery and having that external space, that avenue to share and present my work. I didn’t have any anxiety about the shift in presentation (from public exhibition spaces to commercial). It was a personal challenge, that’s the [only] way I perceived it. I have been in group shows for quite a while, so I felt like I’d already been out there, and that there was a general curiosity, especially from other artists who were aware of what I was doing. I did feel like I was already participating in a national dialogue – not to a huge extent, but on some level.

You’re still quite young, thirty years old, and you’re living in the Yukon. How did Benjamin Diaz become aware of your work? How did that connection get made?

The first time [we met] was in the 2009 RBC Painting Competition, I think he’d been juror or somehow involved in that, and was interested in my painting at that time. But over the years he kind of put it out there that he was interested in maybe doing something. But at that time, and for a couple years previous, I wasn’t sure that I was ready or even interested in working with a commercial gallery. We reconnected after the Oh, Canada exhibition about the possibility of doing a show, and I finally said, “sure, let’s do it.” So it had been a couple of years. And yeah, he had initiated that dialogue, and had [shown] this long-term, genuine interest. Because around then, late 2013 or early 2014, there had been some interest from other commercial galleries. So it was in my head, this prospect of working with someone commercially, and there were these options. But I liked Ben, I liked Diaz Contemporary, and he had shown interest for quite a long time, before other commercial interest had occurred. I don’t know, it just felt good.

It’s an interesting fit, because Diaz has a stable that has, historically and to some extent ongoingly, largely focused on minimalist, conceptual, and abstract artists. In recent years he’s shifted his focus more to suggestively figurative work, particularly artists coming out of Quebec. But you’re certainly still somewhat anomalous in that stable. How do you see the relationship you have to his roster?

I don’t know, honestly. I was pretty surprised. I thought it was sort of funny, given the artists he’s working with. And even now I think I’m a bit of an anomaly in the gallery, yeah. But he was pumped on the work, and happy to encourage and support what I was making. Maybe it’s a one-off, or an item of growing interest for him. I don’t know! But in talking to him and getting to know him more, his past work as a gallery owner and supporter of art [in Mexico], he’s come from a much different place than where he’s at now. So maybe this is a throwback to a former interest and time for him. But that’s a question for Diaz.

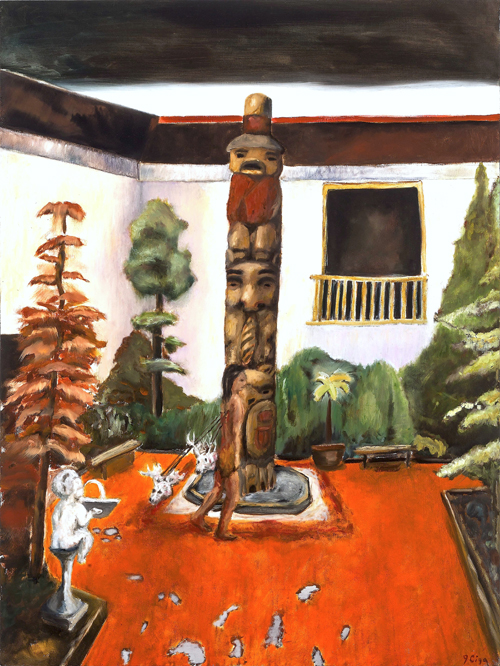

It’s true that your practice shares a few qualities in common with Latin American painting of a certain era, the 1980s, an important touchstone for Diaz’s development as a gallerist first working in his native country. So perhaps, by way of segue, we can discuss two aspects of your work that share something in common with the Latin American genre painting: you centralize performance in your work with the depiction of scenography and staging; and you employ allegories. Can you reflect on where these characteristics and subjects are coming out of?

I think narrative has always been a pretty central focus for me. I tend to just translate through narrative a symbolic representation of the human condition; and through storytelling or mythology it, by nature, centers around the figure, the human being, and action, momentum in the world. So as I’ve developed that internal narrative, it just, maybe by happenstance, always focused on action, maybe banality in action. I’ve always tended to think in those terms.

For sure a large part of that is based on looking at mythology – not just Indigenous or First Nations mythology, but that much larger mythology; how we translate qualities of our archetypal nature. In that Joseph Campbell sense of everything belonging to some archetypal reality that propels action and our human tragedy.

To what extent are you consciously trying to articulate narratives that you’ve learned from the Kaske Dene nation?

Actually that is a point I need to clarify: I wasn’t brought up in a First Nations or Indigenous setting. It’s very much acquired, starting in my late teens through now; I’ve assimilated myself into First Nations culture. Even though I’m Kaska Dene, I was raised pretty urban. So I’m really not trying to hone in on one Indigenous or cultural theme, but rather exist in this mythic space. The work I was making for Diaz was largely about quiet banality. And maybe this is part of growing up where I have, in Whitehorse, where I’ve spent most of my life. There’s this very sublime nothingness that’s always occurring. It’s the core of banality, for me; the way it’s been represented by, say, Samuel Beckett.

Within First Nations, Indigenous – or even non-Indigenous culture – we have these moments of incredible, supernatural occurrence. Like for instance the whole engagement in war, which is amazing to me as a social phenomena – that a mass of people could agree to participate in something so destructive and without real reason. We concoct or engineer these opportunities to go and do these incredible things like kill someone. On some level that’s a supernatural banality. It occurs all the time, it’s ingrained in our DNA. But that it happens is like magic.

Does this explain some of your perceived references to artists like Giorgio de Chirico, Martin Kippenberger, and Marcel Duchamp? Are these examples of a mystic, almost auratic celebrity for you?

Yes. I think that’s one of the powers of making art today. We’re pulling from this vast reference pool, it’s all available and all right there. As soon as you invoke these figures, their work or lives or histories, you’re integrating this whole new realm of descriptive narrative. With those individuals in particular, it requires a certain amount of awareness of their life, background – you know, my mother may not get those references [laughs], but the fact that we’re able to summon these characters and their symbolic nature is really amazing to me.

How are you engaging with the suggested career trajectory of an emerging artist? This includes, of course, finding gallery representation after showing in several group exhibitions, steps you’ve already taken. How eager or reluctant are you to engage with the “gaming” of the contemporary artworld?

I think that’s a really complicated issue. Because of course there’s a very pragmatic reason for wanting to have representation; in order to make work you need to live and support yourself, and that requires a certain amount of resource and economic availability. Grants don’t fill all those gaps. So commercial representation is pragmatic – but it’s also nice because it provides context for an artist’s work, for a time and a place. But it’s a lottery. Some people who make really great, valuable work will never have that opportunity. It definitely gives you a different kind of agency to participate in society, this art dialogue, that you may not have without this acknowledgment. But to me, it seems random.

I work as well. I am the supervisor for an emergency shelter, and have done various kinds of social work for the past eight years. So I pretty much always work. Relying solely on art isn’t my objective. Looking at some kind of long-term reality with art maybe isn’t realistic. Commercial representation isn’t the end of the line. You still gotta live; you still gotta work. But it’s also a reflection of our culture right now. [Commercial representation] denotes a kind of status.

Does the community in the Yukon (where you have an upcoming show) feel close-knit and avid, as I’ve heard it to be?

Sometimes there’s a debilitating amount of support here; people are happy to see and support whatever somebody does. [Laughs] But the contemporary art scene here isn’t super established. And there’s a lot of overlap and interconnection between the arts community – visual arts – and music, theater, writing, whatever. So there’s a lot of connection but not a ton of criticality. The Yukon Arts Centre is the only space that introduces that critical thought and branches out from your classic Sunday-painter stuff. And for me, it’s a great place to try things. When I do things there I tend to show things I wouldn’t show elsewhere, things I would struggle to do in Toronto or even Vancouver. It’s a good testing ground.

How do you regard the problem of access that exists in northern art communities, in terms of its difficulty linking up to commercial representation, for instance?

It’s definitely a complex arrangement that can have an adverse impact on those “invited” or “uninvited.” I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of access. There’s a certain pragmatism for me in connecting to commercial representation. That’s been pretty good for me in terms of having an outside connection – because we lack so much up here. If you’re not already situated in urban centers, the steps involved in connecting to a broader community is really challenging. I can see it with my friends up here who are trying to connect to more contemporary dialogues or contemporary themes than the regionalism of the Yukon art community. I don’t know how or why some people wind up in a national dialogue or have opportunities to show in museums or galleries, and others don’t. Maybe there’s an element of chance. But drawing, for instance, translates nicely into commodity. There’s an ease of access in terms of the medium. If I make a drawing it’s really easy to know what to do with that.

I also work with a local NGO here that’s a part of the national association of friendship centers. The history of friendship centers is to provide services in urban contents to First Nations people who are coming from more rural contexts. So we provide to everyone in the community up here, whether they’re First Nations or not. But the original construction was that it would be a place where people coming from Old Crow, a remote community, or others around here; that it gives them a landing point, or a point of connection in Whitehorse, which is very urban compared to where they’re coming from.

There are a lot of inequities here, a lot of social dysfunction. But recently I’ve been part of a public dialogue that relates to the way that we try to provide service to particularly young First Nations people. In doing that, I’ve been making connections to broader symbolic situations that artists are in, or that I find myself in, in the national landscape. There are a lot of fringe realities that we have to negotiate. Sometimes in trying to negotiate those you have to recognize how to utilize opportunities that are maybe not best-case-scenario, but best-case-scenario for what you have. So that’s one of the things that I’ve been going back-and-forth on.

The inequity of me having opportunities that my friends don’t have. The work and the dialogue that my friends are trying to evoke are meaningful and deserve more recognition and support than what they receive. But it’s like, how the fuck does that change?

And how does that change? Do you have any advice to give, or reflections to offer as an artist who’s successfully bridged the divide? What do galleries need to be doing, or artists, for that matter, to make this disparity a little lesser?

I think maybe some of the more direct actions that galleries can be taking, whether public or commercial, is creating more flexible engagement with people kicking around that fringe. I’m not into the idea of having solely group shows to provide opportunity for emerging or lesser-recognized artists. Because the group show dynamic always carries some loss of agency when you’re a practising artist. Everyone needs to have an opportunity to cultivate their own dialogue. Give artists opportunity to define themselves.

I have a friend, Rosemary Scanlon, and she’s participated in a lot of group shows [here], and solo things around the Yukon, but a lot of the other outside opportunities [for her] are often contextualized within the group-show dynamic. Within the group show dynamic you’re always making work that illustrates somebody else’s dynamic. There’s a loss of definition or agency.

Sometimes galleries do group shows that involve artists they’re not representing. That’s an interesting idea but maybe take it a step further. Maybe once a year, subdivide the space a little more, and show two or three artists in the same space, in the same timeframe, but give them the freedom to do whatever they want, without needing to respond to a theme or anybody else. Because in a practical sense, one of the biggest challenges any artist has is about space. Having space to create work is one, and having space to show work is another. Having DIY spaces, pop-up spaces, is one option; but I think if galleries or public centers looked to use their space in a more neutral way that allows community access, or independent access, once a year, even, and isn’t looking to profit, but to create opportunity – I think that could work for everybody. That could work super well for our national conversation.

Where does one’s initiative, or the accountability for an idea fit into that?

There shouldn’t always be an accountability. It’s like punk shows. You know Minor Threat? You can exist for a year or a couple years, but there is zero accountability to your record company, your fans, and you piece it out afterwards. Different frameworks require a radicalization of the system. Part of that is subverting self-interest, especially in the commercial realm.

How do you feel about being regarded or categorized as a First Nations artist, given what you’ve told me about your upbringing and the broader focus of your practice? Does this labeling feel advantageous or limiting, or both?

I think it’s important for our institutions and critics to look at creating or defining “neutral” inroads for artists that are typically under- or misrepresented. For sure a person’s biography is essential to the work and context they create, but being First Nation or a woman or part of the LGBTQ community, etc., shouldn’t necessarily be the default signifier used to give an artist or their work orientation, value, or purpose. I guess it could be argued that by virtue of existing with the complexities of modern identity everyone and their actions are innately political, but only some are expected to address that politicization as a kind of green card to the art/cultural “bio-sphere,” where they may be forever “niched.”

We need to stop speaking about and for people who have historically been outliers as though they’re “disabled” and requiring, or the recipient of a kind of affirmative action. Rather we need to create space and opportunity for people to speak for themselves about whatever the fuck they want to talk about, because it’s a genuine, needed, and welcome contribution to the dialogue. The next step might be refraining from creating, cataloguing, and weighing people against others in their “default canon” or by some kind of reductive stereotype. The onus there is on both the artist and agents of our cultural systems. Realistically though, I think the impetus is on the critics and institutions to be more discerning in the way they contextualize and program shit, which might require a broad awareness of artists and their practices as well as broad consultation and research. This might also mean being resourceful and flexible about collaborating with people who are more versed or suitable to provide context on a case-by-case basis. I’m sure there are loads of examples to draw on here …

But again, I’m not saying that we should negate biography, just that we should extend the offer of neutrality to allow the person’s singularity to unfold. It’s amazing what people say when they’re not consumed by justifying their presence at the table.

One more point about all that; these thoughts are probably most applicable to the administrators, operators and critics who are “down for the cause” (whichever cause it may be) as it can be a slippery slope into affirming marginalization and using artists to illustrate a niche agenda. There’s probably a lot more that we could discuss and detail more in depth, but maybe I’ll just keep it at that unless there is something you’d like me to define more!? [Laughs]

Joseph Tisiga has upcoming solo exhibitions at the Yukon Arts Centre (March 10 – May 17, 2016), and Diaz Contemporary (October 13 – November 12, 2016).

1 Comment