During a month of dispiriting world news, the work first struck me as a room in mourning: an emptiness indifferent to being filled. White walls of roughly-sliced drywall extend from the building’s interior skeleton, forming vacant platforms. Open shelves refract sightlines, splintering sightlines and casting shadows. Situated near Vancouver’s busy Main and Broadway intersection, Kelly Lycan’s More Than Nothing could be mistaken for construction. A quiet and resonant installation, it presents as art the often-invisible framing and support systems within museum contexts, nudging an awareness towards how languages of display – in photography, architecture, and the materials themselves – shape ideas of value. More importantly, it speaks of examining things often overlooked, and the primacy of matter.

More Than Nothing is the culmination of Lycan’s ten-week, site-responsive residency at the Burrard Arts Foundation. The backstories to the works, while not crucial to the experience, provide deeper layers: each structure loosely references museum displays from around the world that she has photographed and then collected in her archive. A front wall of open shelves is a recombinant memory of those from the Neues Museum Berlin and the Art Gallery of Ontario; a half-partition encountered at the Museé des beaux arts de Montréal hangs from the ceiling above simple plinths, its exposed shelves revealing staircase platforms behind. A curio cabinet recalling those from Mexico’s Museo de la Casa de Cultura hangs from a wall, marked by outlines of shelves signifying their absence; one configuration is re-mounted directly behind it, like a repressed memory.

Deeper in are the exhibition’s most understated rewards: a large frame of recycled and layered drywall, resembling Asian latticework, accentuates the building’s vaulted ceilings, creating a dramatic – yet false – picture window. In a separate room, slabs of bathroom drywall slope against walls painted the same muted jade; the imprint of “Mould Resistant” still gracing its surface, discloses its intended use. Repeated incisions – mapped according to a photograph of a Metropolitan Museum display case – sluices light against the sheets’ curved shadows. Lycan’s sculptural additions are anti-monumental; deliberately not pristine, their edges remain raw, with smudges of different whites, paint drips on unpainted versos, and occasional pencil scrawls. Even hollows in the walls and industrial sliding doors are patched with sheetrock, softening the architecture. Utilizing the language of Minimalism, Lycan dishevels it slightly, as if to pry it from consumer culture’s appropriation of the term as a lifestyle trend – which, while seemingly about paring down and obtaining freedom, is more about the privilege of acquiring to upgrade and streamline. Her practice certainly relates to Minimalism’s original intentions to blur the distinctions between painting and sculpture, and emphasize anonymity over authorship. Lycan brings searing focus towards light, weight, and space. Yet through slight interventions she complicates the motivations of artists working fifty years prior. Her provisional aesthetic reflects the precarious economies around contemporary artistic production: the idea of creating with very little, in a society of excess waste.

Kelly Lycan, “More Than Nothing (Museo de la Casa de Cultura, Todo Santos, Baja, Mexico),” 2016. Photo: Dns Ha.

Lycan’s ability to communicate aura through inexpensive, utilitarian hardware-store materials democratizes the presentation techniques adopted by museums and department stores, demystifying them to share an accessible beauty. Her choice of drywall – a ubiquitous yet invisible building skin – suggests the incessant construction underway in urban centers, foregrounding ordinary materials we take for granted. It brings to mind the work of Michael Asher – particularly his interventions within New York’s Artists Space in 1988, where he used sheets of unpainted drywall to vertically extend the gallery’s walls, which had been deliberately constructed to stop short of the ceiling, creating the illusion of floating planes. Restoring their neutrality, Asher drew attention to the sculptural pretenses of architecture and their participation in amplifying affect. Lycan also wants us to see the theater set exposed; she wants us to see materials’ traces, which express their shifting qualities gradually, if given time.

What Lycan shares with sculptors such as Liz Magor is an affection for the devalued and forgotten – stuff left by the garbage bin, sweaters from Value Village – and a desire to present these materials as art, exposing the frameworks that influence ideas of value while acknowledging their own participation in the theatricality of presentation. Magor’s recent works are noticeably anti-monumental, perhaps a reflection of the times and conversations between the two. Yet while Magor’s technical virtuosity often performs verisimilitude, articulating discrete works and human presence – say, in the muted arrangements of Good Shepherd (2016), or her series All the Names (2016) – Lycan’s subtlety exists in letting things be things, her attention to the behavior of matter first (not necessarily in relation to human activity), and of letting works blur into one another. The figure is almost always absent, if barely implied.

Kelly Lycan, “More Than Nothing (The Metropolitan Museum, New York City, U.S.A. II),” 2016. Photo: Dns Ha.

Lycan’s intrigue with the frameworks surrounding the presentation of art and ordinary things could be interpreted as institutional critique. Yet unlike Asher, or more recently Duane Linklater – whose interventions into the walls of Toronto’s Mercer Union in the work What then remainz are concerned with questions of Indigenous sovereignty, and of opening existing structures for greater inclusion within the ongoing contexts of settler colonialism – her investigations lean towards making visible these structures’ participation in creating value, reveling in the materiality and structures as art, while knowingly seduced.

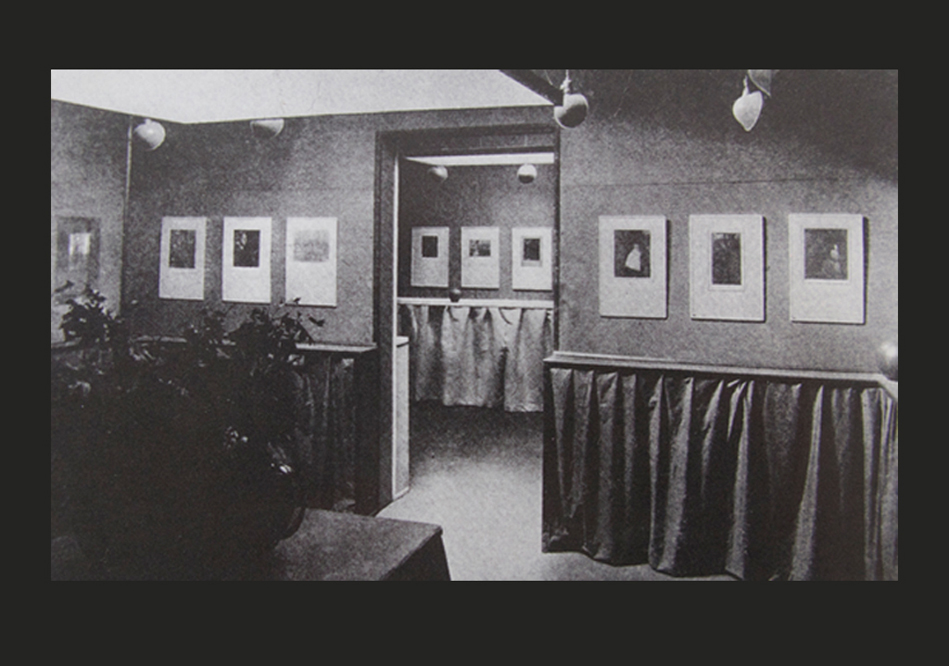

What distinguishes Lycan further from artists such as Yugi Agematsu (whose collection of urban detritus is also presented in a minimalist aesthetic), or Allyson Vieira (whose sculptures, also made from industrial waste materials, evoke slick forms recalling ancient ruins), is her historically-specific focus on photography’s influence on how we view form. She is adept at capturing the fluidity between forms – painting, sculpture, and photography – as they transform and influence one another. In Lycan’s previous and concurrent installations, materials also perform, and the set is made apparent. For her 2014 exhibition at Presentation House Gallery, she created 291: From the Faraway Nearby, a full-scale sculptural replica of the historic New York gallery 291 based on a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz – in essence, a black-and-white photograph one walks right into – in essence, a black-and-white photograph one walks right into. At Surrey Art Gallery, this past Fall, her Documentation Study (Rumination #3, SFU Burnaby) reveals the instability of matter’s identity, hovering between sculpture and painting. Originally a studio still-life, once photographed it transforms to flatness; mounted on Mylar, it wavers delicately in response to the gallery’s ventilation, becoming sculptural once again. All materials reside within the same pale-white palette, suggesting effacement, while clouding the weary, binary terms of art and non-art.

Alfred Stieglitz, installation view of the Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White exhibition at Gallery 291, New York City, 1906.

Kelly Lycan, “291, From the Faraway Nearby,” 2014. Installation view, Presentation House Gallery. Photo: Kelly Lycan.

Lycan understands the index – particularly what she describes as “the human desire to track, enlarge, and miniaturize ourselves and our lives through photography” – but more so memory’s mutations, as images recirculate in different contexts. Accordingly, she folds references into her work, from Brancusi’s studio experimentations with photography and sculpture to aspects of her past installations. These create overlapping, mixed-up recollections. The studio is a recurring subject, which Lycan engages to emphasize both process and material agency. She describes much of her studio work as “involuntary compositions … how things make themselves.”

However, there is a risk in this effort becoming too referential, of conversations becoming too insular, or of romanticizing the studio process within the history of art (a topic approached by numerous artists, from Dieter Roth to Rodney Graham). Perhaps Lycan senses this. For halfway through More Than Nothing, she invited five artists to respond to the exhibition, shifting a singular contemplation to diverse conversations between objects, humans, and the architectures that supports their display. She asked that these artists make work that specifically considered the lightness of color and weight. Through collaborative placements, each one activated Lycan’s platforms, transforming still-life into vibrant matter.

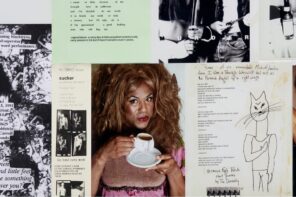

Populating Lycan’s front window shelves are Deborah Edmeades’s Artists, Mystics, and Suffragettes (A-Z), 2016, a collection of stoic papier-mâché busts whose psychedelic eyes suggest special powers. A quirky “list-in-progress” accompanies the work, including lesser-known feminists and female innovators such as 18th-century Sojourner Truth, an African-American abolitionist and women’s-rights advocate. I sense Edmeades is deliberately subverting expectations of the index and playing with the exhibition’s in-process nature. The sculptures, all seemingly made from a generic mould, point to how history becomes flattened through the repetition of representation.

Marina Roy, “Newspaper Works: Real Estate (Valentine’s Day, 2003) and Wedding announcement (Valentine’s Day, 2003),” 2014. Photo: Kelly Lycan.

Marina Roy’s encaustic-coated magazines share Lycan’s process of erasure through “whiting out”: stacked on low plinths, the drippy transparent surfaces render content unreadable. Leaning against a wall, two of Roy’s earlier Newspaper Work (2004) paintings, similarly treated, eradicate text from the photograph, highlighting the page as a space of unexpected juxtapositions and interpretations. Her emphasis on materiality evokes a reverence for printed matter amidst its 21st-century dematerialization. Nearby, Justin Patterson’s Dream Bullies (2016) – felted, fleshy miniatures of body parts, fashion accessories, and unidentifiable things – are draped over upturned shelves and tucked into unexpected corners. Close-up, a polished red nail or ear canal occasionally emerges as an identifier. Similarly, Lucien Durey’s Sonora (2016) – spike-y, tubular objects made from metal pull tabs (or dollar-store fasteners) – retain their open-ended identity as things. Populating the non-functional curio cabinet, they could equally reference the resilient vegetation of the Sonora desert.

The strongest intervention, and by far the most sensitive to Lycan’s original intentions, is Natalie Purschwitz’s Sugar is Not a Vegetable. A transparent railing fashioned from cheap pink cellophane, it extends seamlessly from Lycan’s latticework drywall. Perched within it, and barely visible, are mimicries of plastic cups, made with pieces of clear tape. Purschwitz’s works are like light-catching whispers that speak to the medium’s delightful yet empty fulfillment.

I can’t help but read these acts of participation as a link to Lycan’s past involvement in the artist collective Instant Coffee, whose key motto “Get Social or Get Lost” emphasizes the discursive aspects of art-making. In A Light Response, the gallery transforms into a studio that references its own history, in salon culture, as arguably the first exhibition space, a place of rich social and intellectual exchanges. The artists all share a sensitivity towards revealing the vibrancy of matter not as an instrument to fulfill human desire, but as things one can spend time with.

Spending time with things in their physical materiality is a key part of studio practice, though no longer limited to the traditional studio. Lycan and her accompanying artists are part of a wider sensibility intent on revealing process, the performativity of materials, and everyday relationships to objects. Perhaps this is a push-back against the idea of “post-studio” practices, and against an increasingly virtual world. Recent exhibitions in Vancouver articulate a similar spirit: Kitchen Midden (Griffin Art Projects) brought together a range of objects that community artists live with; The Last Waves (Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery) was a collaborative installation by Julia Feyrer and Tamara Henderson, also adopting the trope of the “set,” with messy tabled arrangements in states of decay. 5 Tableaux (It Bounces Back) (Or Gallery), a performance by Chloë Lum & Yannick Desranleau, relished in entropic materiality between humans and things, leaving the performance’s remnants to comprise the exhibition. Vancouver Special: Ambivalent Pleasures (Vancouver Art Gallery), a current survey featuring works by Vancouver artists created over the past five years, also showcases a deep material engagement. While presented very differently, each demonstrates how materials are live entities and sources of subconscious, intuitive power. This focus, while not new, has been obscured by the predominance of photo-conceptualist (and predominantly male) narratives for which Vancouver art initially became known.

Significantly, these material engagements connect to broader, interdisciplinary discussions around new materialisms and speculative realism – specifically the focus on the agency of matter, and away from the anthropocentrism that has long dominated subject-object relations. Parallel movements in contemporary visual art, while also not “new,” suggest artists looking to materials for insight at a time when the human world has become too fraught. This is not to say that material relations are more important than human ones, but they can be foundational, if intermediary, to how we encounter the wider world in non-hierarchical ways. Amidst social, political, environmental, and economic precariousness, rejigging the ways we engage with our material environment is not frivolous or apolitical, but urgent. A reprieve from our own narcissism: also a good thing.

Writing on Thing Theory in 2001, Bill Brown proposed a new materialism that would grant objects their potency, “to show how they organize our public and private affection.” Eight years later, Jane Bennett, in Vibrant Matter: The Political Ecology of Things, expands on this thread, asking: “how would political responses to public problems change were we to take seriously the vitality of (non-human) bodies … the capacity of things – edibles, commodities, storms, metals – to act as quasi-agents with tendencies of their own?” While our current answers may only be murmurs, the work in More Than Nothing and A Light Response reflects this transitional, humbled state. Here, collective and bare vulnerabilities nudge us towards different ways of engaging and communicating with things. I suspect these things are trying to tell us that what little we have, is just enough.

1 Comment