I think of them often. I knew Felix best. Jorge I never knew well. I feared and admired AA’s bite and sophistication. But I looked up to them all and, now that the ashes of General Idea are scattered, I often find myself thinking of how Felix and Jorge died, or rather, how they lived, and made their work as death drew near. General Idea was, among so many things, an enquiry into what an artist might be. They claimed to be “a framing device within which we inhabit the role of the artist.” Pretending to pretend, they threw off alternative visions: babies, poodles, doctors, or poor pathetic hunted seals on an ice flow. Then Felix and Jorge stepped off this mortal coil. How they left is the last image they could leave us, their last heartbreaking exploration of the frame to which they devoted their lives.

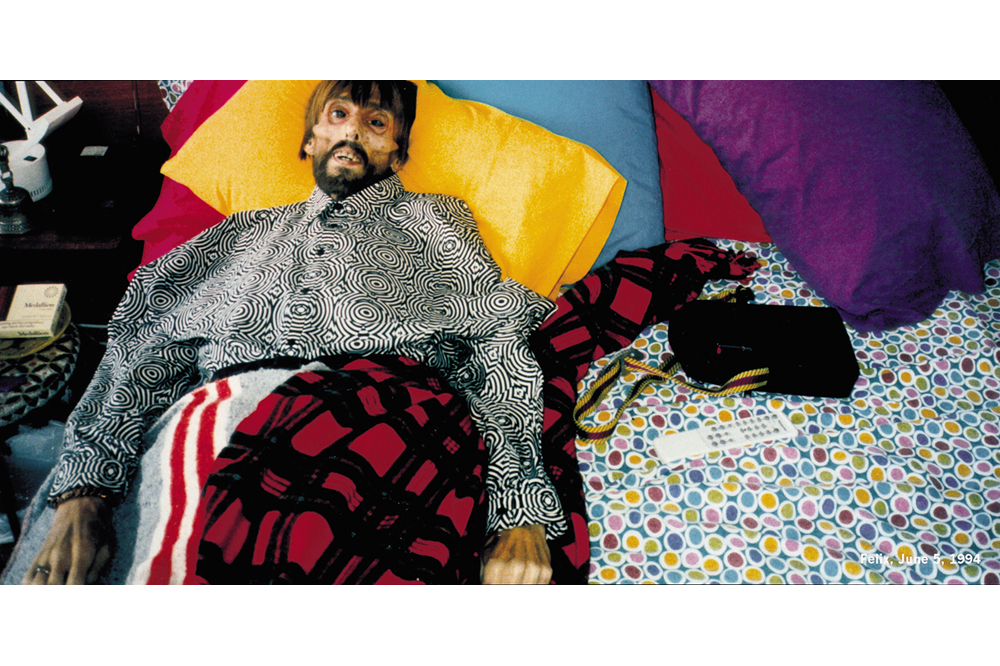

To the very end, Felix – an artist to his toes, an artist to the last – was at work on the Infected Mondrian paintings. The story I heard was that he finished the final one, laid down his brushes, and died the next day. That morning AA took his famous photograph, Felix Partz, June 5, 1994 (1994/1999), one copy of which is now in the National Gallery of Canada, while another resides at the Whitney, a gift of Mark Jan Krayenhoff van de Leur, architect and AA’s husband.

Kaleidoscopic and ghastly, it shows Felix, his face almost collapsed, eyes permanently wide and sunken, dressed in a vertiginous black-and-white shirt that resembles the Op Art he loved. It looks like waves from a hundred simultaneous pebbles hitting water. Close at hand are his TV remote and tape recorder. His once-beautiful, now ship-wrecked head rests on yellow, red, blue-grey, and purple cushions, no riot of color but something like the intense patterning of the ziggurat paintings he began in 1968, before General Idea had quite formed, which later were absorbed by G.I. into the vast project. I suppose the image is ghastly; now I find it beautiful. How unflinching it was of AA to take this image in death, the image of the man who had been for so many years his intimate collaborator, who had once been his lover. A body abandoned by its soul, all the battles, conflicts, and brilliance are evaporated. Or are they condensed here into something new? I often show it to my students, sans trigger warning. I couldn’t bear to dilute the shocking, ghastly, and beautiful image.

He didn’t want to die. Caustic, and completely unlike Jorge, he wasn’t accepting. Death was no passage into the mystery. He had been working on the Infected Mondrians. I first saw one in their penthouse in the Colonnade on Bloor Street, where he’d encouraged me to marvel at his efforts in gardening. “These are my black pansies,” he said, underlining the phrase. The painting hung above the fire place, of all places. I stood surveying it across the sofa and yards of snowy carpet. It looked for all the world like a classic Mondrian. At the same time, it felt wrong. I couldn’t figure it out. Finally AA came up behind me and whispered, “It’s the green.”

Of course: the small rectangle of green along the lower right edge. After his early landscapes, Mondrian banned green from his paintings because it was too reminiscent of nature. G.I. reintroduced it, contaminating that lovely clarity. It seemed a terrible admission: that Felix and Jorge were being killed by nature. In 1975 G.I. had laid out their program in FILE’s famed Glamour issue. “We had to become plagiarists, intellectual parasites. We moved in on history and occupied images, emptying them of meaning, reducing them to shells.” Now Felix and Jorge were dying of a virus that was like a parasite, attaching itself to a T-helper cell and fusing with it, turning the immune system against the precious body it meant to protect. Oh, Image Virus, I wish I’d never heard your name.

But the Infected Mondrians ring false. The paint-handling shows none of the minute adjustments in which Mondrian engaged, that patient narrowing or broadening of the black bands until a dynamic equilibrium was finally reached. Where Mondrian had to struggle, G.I. only had to mimic. The surprisingly generous paint application of their Dutch model isn’t there, which follows in part from what surface underlies the paint. Mondrian painted on canvas. The infected versions are done on foam core, oh mere expedient, its bubbly thickness visible in the gap between the painting and its recessed frame. Up close, General Idea’s Mondrians look like simulations, deliberately unconvincing, as though designed to disappoint. But from a distance, they look pristine: the almost-perfect image of a Mondrian. When these perceptions combine the result is something at once lovely and bitter.

He finished the last Infected Mondrian, laid down his brushes, and died the next day. How admirable! But the story turns out not to be true: AA tells me one Mondrian remains incomplete. I imagine it as Felix’s long ellipsis … Anyway, he was already at work on something else, trying to figure out how to transmute Mondrian’s last painting into something that could be General Idea. Vita Brevis: only a pencil sketch exists, a spider’s web of marks too muted to photograph. Felix grew too faint to live, but in death he was too vivid not to photograph.

* * *

Jorge Zontal was born Slobodan Saia-Levy in 1944 in an Italian internment camp for foreign Jews, likely either Montechiarugolo in the province of Parma, or Fossoli di Carpi in the province of Modena. After Mussolini’s despicable regime fell and he took his place on a meathook, most prisoners were freed, then rounded up again as German forces took control of the north of Italy. In the confusion of those days, Jorge’s mother escaped to Switzerland with her baby, while his father was captured and sent to Auschwitz. Half a century later, AIDS brought that history back. A week before his death, Jorge asked AA to photograph him, standing by the floor-to-ceiling windows of the apartment. “Jorge’s father had been a survivor of Auschwitz, and he had the idea that he looked exactly as his father had on the day of his release. He wanted to document that similarity, that family similarity of genetics and of disaster.”

The almost life-sized sepia photographs are calmly disturbing, if such a thing is possible. Something akin to kindness. Seen from a distance in two photographs, and closer in the third, clad only in shorts and shoes, Jorge looks out over Bloor Street, looking variously relaxed or focused and intense, surveying the world in its busy distraction. Had we but world enough and time. He seems so at ease, so very much the emaciated man of the house. In one image, he looks almost coquettish, almost coy. He could be a very late entrant to the Miss General Idea Pageant (by twenty-three years), but praised nonetheless for “having internalized Glamour in the face of Death,” as the jury might well have declared.

But it’s Jorge’s ability to mimic the sight he no longer had that moves me so much. I know he needed AA’s instructions, “Open your eyes a little more; no, not quite that much”: a fine final collaboration, like love. It is said that the eyes are the windows of the soul, but I don’t believe in the soul. The photographs fuse these together: blind eyes which cannot see, the windows through which he convinces us he can see, and the soul in which I don’t believe but almost see.

At his birthday party, Jorge gave us the other side of sight, which is being seen, being an object of sight. “Fifty Years of Jorge Zontal” read the invitation. It was an accomplishment worth celebrating. But when I arrived at the penthouse, Jorge was nowhere to be seen. Oh no, I thought, he’s too sick to appear at his own party. My mood collapsed, but there were martinis on hand, to modify one’s feelings. I noticed, now and then, someone slipping from the party, disappearing for a brief spell. Perhaps they were quietly visiting the dying man in his bedroom, saying their farewells. A few drinks later, someone sidled up to me and said, “Jorge will see you now.”

I imagine that phrase was carefully chosen. I followed my guide to the long corridor that led to the bedrooms. It was surprisingly dark. As I entered, a spotlight came on at the far end. In the well of light Jorge was suddenly visible, seated in his wheelchair, adorned in a white ruff collar, heavy vest, and ruffled sleeves. When his assistant bent to whisper, “Andy is here,” he lifted a gloved hand to his heart where it rested for a moment. No words. His last performance was a painting come to life in the darkness of that time, A Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest by El Greco. But the face and body now were stretched by suffering, in the artificial light of an alien century. It was terribly intimate: each time he appeared it was for an audience of one, and one only. His last performance promised nothing – what promise could he make when no future lay ahead of him? But it bound each person to him more tightly than before. Jorge had no future, so he took the form of the past, appearing as an instant from art’s rich history, the history he was about to enter, a brief flash that said, remember this.

His 50th birthday was January 28, 1994. Five days later he was gone: February 3.

Great piece Andy. A tear in my eye.

Thank you Andy, for a powerful and very original text about three original and very powerful artists.

This unforgivable photo was shot by AA without Felix’s blessing or approval… and then produced as a public billboard heightening the sheer callousness. Felix was a close and very dear friend of mine, and I will never forgive AA for this abhorrent trespass on Felix’s dignity.

I pray that the NGC will never exhibit their ill-advised acquisition of this insensitive and criminal image… otherwise our Felix will never be able to deservedly rest in peace.