Architect Paul Williams used to sketch out plans, virtuosically, upside down. He became famous for this skill – most writing about him mentions it. He’d position himself across the table from white clients who wanted to hire him but found his skin color discomfiting. He’d then brilliantly cater to their desires without requiring a physical nearness. In his 1937 essay “I Am a Negro,” Williams termed this talent a “sleight of hand.” Stories about this and other tricks and burdens of his trade appear in Tony Cokes’s new video work The Will & the Way…Fragment I (2019). Cokes’s piece, accompanied by a Radiohead-remix soundtrack, currently loops on a screen in the living room of the one house Williams designed for himself. Hannah Hoffman acquired the house last year, and Cokes’s exhibition, titled Della’s House, is the first show there (any plans for future show are yet to be determined). It always matters where a gallery is – the Boyle Heights protests drove that home – but the context of this one announces itself, immediately and dramatically, from the moment you turn into Lafayette Square, a planned community with one way out and one way in, with iron gates marking its boundaries. These houses, until recently, rarely went on the market and hardly anyone drives into the square without reason. A neighbor, sitting in his bay window across the street, watched me closely as I parked, and then again as I drove away.

Lafayette Square, founded in 1913 by George Lafayette Crenshaw (a developer partly named after a French marquis), used to be an all-white, wealthy enclave. Paul Williams, whose work contours Los Angeles in more ways than most of us realize, designed for clients there: regal, period revival homes in the kind of stylized yet comfortable California grandeur he did so well. Then, in 1951, a few years after a federal court deemed illegal the land covenants that had kept out residents of color, Williams bought up one of the last remaining lots and designed a home unlike his others. California Modern, it had a minimal, clean-lined, white exterior, though the inside featured curved walls and an entryway staircase with leaping gazelles attached to the railing (“what comes to mind are the handsome homes of the Thin Man movies,” wrote a former neighbor). Williams and his wife, Della, left the single-story South Central house in which they’d raised their family. Their granddaughter, Karen E. Hudson, remembers that neighbors distributed fliers claiming that the new black resident would drive down property values. “This was a famous architect […]! It wasn’t like Jack the Ripper was moving in or something,” Hudson told The New Yorker in 2005.

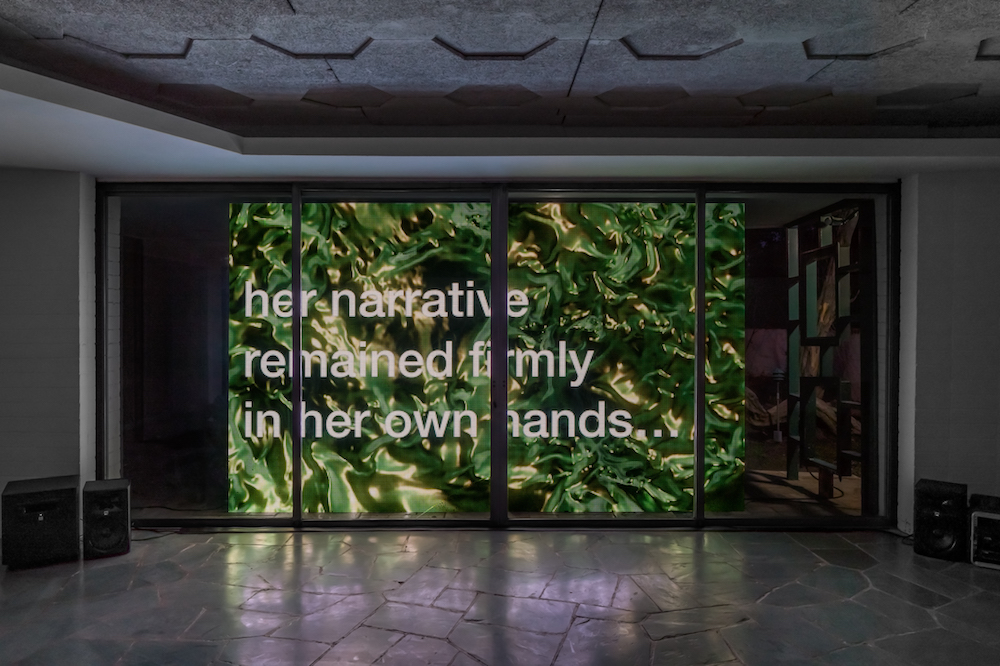

Tony Cokes, “Della’s House” (installation view), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo by Elon Schoenholz.

Hudson owned the house until she sold it last year, making Hannah Hoffman Gallery the first non-Williams-family resident. Hudson also wrote the only two Williams monographs, and the 1994 book, The Will & the Way, from which Cokes borrowed material for this exhibition. A children’s book, The Will & the Way is a fictionalized, but historically-accurate, biography written in Williams’s voice. Most of the architect’s papers, stored at the Broadway Savings & Loans that he designed, burned during the Rodney King protests, a fact that makes creative retellings like Hudson’s particularly helpful. You wouldn’t likely know, however, from watching Cokes’s videos – or reading the restrained press release – that Hudson, rather than Williams, is the artist’s primary source (though Cokes does include citations at the end of each video). In Williams’s former living room, large white sans-serif text floats against an undulated, digital blue ocean: “I would ask if they entertained at home or in a hotel.” This is Hudson-as-Williams on how to make rich whites comfortable. “I could not forget that I was not accepted the way other architects were.” Nearer the sleek marble fireplace plays another video, The Queen is Dead…Fragment 2 (2019), this one a tribute to Aretha Franklin. Text from New Yorker editor-in-chief David Remnick’s 2016 tribute to the Queen of Soul plays against a backdrop that resembles shifting, shimmery gold wrapping paper, as Franklin sings.

Tony Cokes, “Della’s House” (installation view), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo by Elon Schoenholz.

In the lanai, inspired by a terrace-to-garden room in a Jamaican country club, an expansive screen obscures most of the garden view. Here, over lush green graphics, we’re again regaled by journalists’ memories of Franklin. A smaller screen nestled against a curved brick wall continues recounting Williams’s biography. “I’ve never made a house so trendy that when the owners wanted to move, no one else would be interested in buying it,” says Hudson-as-Williams. This comes from the part of the book about the early 1950s, when the architect and Della, already grandparents, designed this Lafayette Square home, customizing every piece of furniture. The constructed narrative – both in the book and Cokes’s videos – incorporates actual quotes from Williams, which are unsurprisingly more sophisticated than the children’s biography, but also reticent. “Buildings, too, must wear style that will give them an association to a certain period of time,” Williams wrote, reflecting on the contours of success at a time when the international architecture community had just begun to recognize him. “How carefully the architect balances the elements in his work, to a good degree determines the stature attained by him in his profession.”

In Hudson’s book, these pull-quotes play the clear role of substantiating her narrative. In Cokes’s video, they have a slightly schizophrenic effect, the simplified narrative and the architect’s more nuanced language competing with each other to tell the story of a man too seldom written about. Though it syncs jubilantly with the background graphics, the soundtrack of Radiohead remixes adds to this disjointedness, especially when contrasted with The Queen is Dead videos. It doesn’t help that the house, stripped of furniture, shows its wear, nor that the gallery has placed plywood over the window and floor in the living room – most vintage photographs show that room lushly carpeted – and over the dining-room window. In a show that appropriates Williams’s biography, inside a home that he built for his family, the architect feels weirdly distant.

Tony Cokes, “Della’s House” (installation view), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo by Elon Schoenholz.

Soon after Hannah Hoffman Gallery closed its Hollywood space last spring, Hoffman gave an interview to Whitewall. “2018 is going to be a year of transition, and there will be a period of spacelessness this fall,” she said. “We have been talking a lot internally about what a gallery can be when you remove the expectations of a particular kind of space and schedule.” This made it sound as though the space would try its hand at being nomadic, and indeed, in January, the gallery opened a show of mercurial L.A. artist D’Ette Nogle’s work in a Public Storage building in West Adams. But the Williams house could hardly be further from spacelessness, and comes with a kind of responsibility that the artworld in Los Angeles (and certainly elsewhere) hasn’t always been good at taking. When a curator “rediscovered” the only building, a Compton Avenue church, that Rudolph Schindler ever built for black clients, artworlders gushed about the good frame and clean lines, the white walls and beautiful design made for artwork – such as the Robert Barry show installed there by Thomas Solomon Art Advisory. They conveniently ignored the many years when African American congregations stewarded the building, even once painting its walls blue, at a time when the high-culture industry barely noticed the neighborhood.

Williams’s legacy has already been victim to such unconscious prejudice, like when the director of the prestigious Harvard Westlake school proposed moving a Williams house from the still-exclusive, very white Holmby Hills to La Canada Flintridge, 38 miles east. “We can relocate the house to another neighborhood where he also might not have been able to live,” the director said in 2005. Cokes’s Della’s House tries to avoid such easy elisions, though it is his work in the dining room, not sourced from biography at all, that resonates best with its context. His 1990 Fade to Black plays on a monitor installed on a wall still adorned with a mural of branches and blossoms. The tall mirror on the elegant built-in buffet against the opposite wall reflects the video back. Images from unquestionably racist Hollywood features, some made by and with the kind of people Williams elaborately housed, float in the center of the screen, while titles of other racist films appear above while a searching narrative runs beneath: “but this recognition is always already a mistaken identity.” Sometimes words, bright against all-black, fill the screen: “I don’t understand what’s going on.” An audio collage of music and male voices discussing casual racism complicates the work, which strips bare, but offers no solution to, the kind of volitional, criminal mainstream obliviousness that still sidelines Paul Williams’s legacy.

I’m a resident of Lafayette Square. The author might want to have looked further into how when Ms Hoffman bought the Williams’ home, Hoffman assured the family, who had concerns that she might misuse the property for commercial purposes, that she would indeed live in it, and respect it as William’s would have wanted. Instead, she chose not live in it, and converted what was once a beautiful, iconic home of one of LA’s most notable architects, into a for-profit commercial gallery, replete with staff, visitors, and all of the parking/traffic concerns that those bring. Not only is this strictly regulated when done in a residential neighborhood, it is blatantly illegal in one which is a Historical Preservation Overlay Zone and which has extra protections against commercial use. Furthermore, the home itself is a historical-cultural monument, and has additional restrictions on such uses. Besides that, it isn’t how Williams (or his family) would have wanted the home to be used, something Hoffman was acutely aware of when she purchased it.

While there is always a tension between preserving a space and using it in a contemporary way, if ever there was a classic example of the most objectionable kind of gentrification/appropriation, neither respecting the structure, the neighborhood, or Williams himself (or his family), this is it. And given this lack of respect, nevertheless using it as a venue for subject matter that can be problematic for anyone trying to tackle, and one which blatantly uses the Williams legacy without inclusion or consideration of the family. To many of us residents, Ms Hoffman’s “gallery” is, more prominently than any of her exhibits, a clear display of her self-interest at worst, or at best, a terribly tin ear.

Thank you for this —

I have never seen a house built in such a creative way as it truly sets the idea of a house apart. I think I will also try to get a similar house when I am able to afford it in a couple of years.