Titus Kaphar came into the limelight soon after Time magazine commissioned him in 2014 to make a painting for one of its “Person of the Year” finalists, the Ferguson Protesters. The painting, Yet Another Fight For Remembrance (2014), is a 4-by-5-foot tableau depicting a group of protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, streaked of white paint, as if erased from the picture plane or, more figuratively, the annals of history.

Since then, the 43-year-old artist – in addition to receiving numerous accolades for his work, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 2018 – has been making paintings and sculptures that confront history head on: how it’s being told visually, and what is wiped from the record. Using various techniques such as cutting, tar dipping, shredding, and crumpling, the artist exposes the troubling histories of our nation’s past, while also unearthing those that have been hitherto forgotten or untold.

Terence Troulloit spoke to Kaphar on his upcoming shows at Mass MoCA and MoMA PS1, his humble beginnings as an artist, and what to do with confederate monuments.

I wonder if you could start by talking about your own evolution as an artist. It’s my understanding that you came to art later in life, correct?

I did. I was in my mid-twenties when I decided ultimately that this was what I wanted to do. Prior to that I thought I wanted to be a rock star. [laughter]. Maybe I still do a little bit. I’m a bass player.

Let me step back a little bit. I didn’t do well at school. I failed most of the classes that I took. I got kicked out of kindergarten. I was suspended very often in high school. I wasn’t a good student to say the least. I went on to junior college only because I was trying to impress a woman who would later become my wife. Long story short, I took an art history class in junior college and it opened up the world to me. It made me realize that I had a kind of visual intelligence I never knew existed, and that if I could understand the world through images – and sound also – I could figure things out. So I went from being a very poor student to being on the dean’s list, and that was mind blowing to me. That sent me on this journey to pursue art and it started off as this very art-historical approach. I was taking as many art history classes as I could find.

So you started more on the research side as opposed to the art-making side.

Exactly. I didn’t take my first studio art class until I had already done two years at junior college and transferred over to the state college [in San Jose, California]. I was so focused on art history because so much of what was being told to me – “the canon” – had so many glaring absences that were very loud to me. So my work, from the beginning, really looked at those absences.

I started taking this traditional approach to painting and decided to squash it together with other elements inspired by Rauschenberg, who was willing to pull things apart and cast things into a composition, and Sam Gilliam, with his willingness to explore and experiment with the canvas, and Fontana’s willingness to cut into a surface and see what the implications were through this hole in the canvas. So I have this love for representational painting and this love for post-modernist gestures, these actions that disrupt the history of art making. I think smashing those two things together is how I ended up making the things I’m making right now.

This brings me to your ongoing project, “Monumental Inversions,” a series of sculptures looking at traditional monuments of our nation’s forefathers. One example is Language of the Forgotten (2017), currently showing at Mass MoCA. In it we see a cut-out mold of the bust of Thomas Jefferson’s head in profile, and in front of it an image Sally Hemings – a female slave believed to be the mother of Jefferson’s children – etched on a piece of glass. This series, for me, really brings into focus the conversation around the removal of confederate sculptures in the South. The argument for taking them down is often appropriate. But for some, the removal of these statues is an act of erasure: the disappearance of proof of a troubling past. “Monumental Inversions” seems to reconcile these two arguments by creating a space that equally exhibits the absence and presence of the figure. I’m wondering if you could speak to that and your approach to making these works.

I actually just got back from Charlottesville. I did some talks at the University of Virginia where they are dealing with this issue very directly, whether they like it not. We all know the horrors that took place there in August 2017. And I think people are really still recovering from that. I’ve talked about this in public before, but this time it seemed to have a little bit more fire, more urgency. Publicly we’re having a very binary conversation about these sculptures, and it’s by and large one group saying keep it up and the other group saying take it down. And if the conversation is binary then my opinion is to take them down, but I don’t think it has to be binary. I think there are other options. If we choose to engage artists on this subject more, I think we would be getting a different set of answers to these questions. I imagine a possibility where contemporary artists are engaged to make public works that stand in the same squares as these problematic pieces that we are forced to walk by daily. I think an important part of the conversation is to take those sculptures off of their pedestals, but leave them in the squares and bring those contemporary artists to the space. Put out some request for proposals, engage the community, and get artists making pieces that they feel speak to the future. Those areas then become spaces of civic dialogue, places where we can commit to having those difficult conversations that are absolutely necessary for us to have if we’re actually going to advance.

Those ideas also play into your artistic practice. A lot of what you’re doing, whether it’s sculpture or painting, is creating a balance in how we view our country’s difficult past. There’s almost this act of negating, or an element of pulling away, from the image of Jefferson to reveal the story of Sally Hemings through this glass vitrine.

So there are a couple significant parts to the material and the approach to the “Monumental Inversions” pieces. You know, we think of molds as a means to an end in a sculptural process. The mold tends to be the thing that gets us to the ultimate object. But I’m fascinated by the mold itself because the mold is also representative of this idea of potentiality. The mold is at once the absence of the object itself and all of the potential for it. And so for me to take these significant and important figures – the founding fathers – and represent them as molds, as potentiality, there is a way where you can recognize both the negative and positive things they did in their lifetime. We either deify or demonize our founding fathers and neither one of these extremes is beneficial from a historical point of view. And so with the works in this series I attempt to stack on top of each other the narratives of the founding fathers – that we have been bombarded with for our entire lives – and the narratives that we have always known but swept under the rug and didn’t want to bring to the surface.

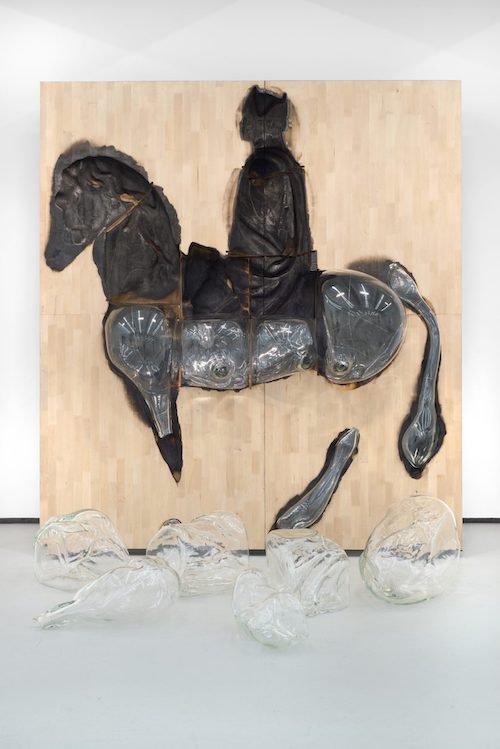

Titus Kaphar, “Monumental Inversion: George Washington” (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery.

Let’s pivot and talk about your works that deal with the fraught history of Yale and Princeton. One is a painting called Enough About You (2016), inspired by a painting at Yale that depicts Elihu Yale, the university’s namesake, with an enslaved boy; and the other is Impressions of Liberty (2017), a sculpture, also part of the “Monumental Inversions,” depicting a negative impression of the bust of then president of Princeton Samuel Finney and the image of a family of slaves etched onto a glass vitrine in front of the carved block. [The enslaved figures harken back to the six slaves that Finney sold on campus in 1766.] Could you talk about that process of working with these two institutions? Was it a collaborative effort?

Generally I do all the research myself. In my studio I have a couple of research assistants as of part of my practice. So much of my work does deal with research. It’s a really important part. So we look into all kinds of things that may never become artwork, but it’s important for me in terms of my process. With Princeton it was slightly different because the university had already done much of the research. By and large, however, I do not like commissions unless I get complete freedom because my practice is such that things often go in a different direction. And if the painting tells me it wants to go left, regardless of what the commission is, I’m going left.

And that wasn’t the case with Yale?

No. Enough About You wasn’t a commission. At the time Yale was having these discussions, or attempting to, about a number of different race issues. There was this painting, which showed Elihu Yale with two other white men signing some document, and this young black boy on the side who was serving them – he had a steel collar and a lock around his neck. And so that painting is something that the university owns and it was challenging.

When I first saw the original painting, I began to do some research on that little boy. I could find everything I wanted about every other detail in the painting, but there was nothing about him. No history. And so I wanted to find a way to imagine a life for this young man that the historical painting had never made space for in the composition: his desires, dreams, family, thoughts, hopes. Those things were never subjects that the original artist wanted the viewer to contemplate. In order to reframe the discussion, I decided to physically take action to quiet [and crumple] the side of the painting that we’ve been talking about for a very long time and turn up the volume on this kid’s story. And that’s the reason why I started that painting.

So I want to move on to your group show “Suffering From Realness,” which opens in April at Mass MoCA, and the exhibition at PS1 “Redaction,” a collaborative project with poet Reginald Dwayne Betts, which opens March 31. Can you tell me a bit about both shows?

“The Redaction” project draws directly from lawsuits filed by the Civil Rights Corps on behalf of people incarcerated because of an inability to pay court fines and fees. The project uses both the images of these men and women and the actual text of their complaints. Betts used the legal strategy of redaction to create poetry out of these complaints and I employ printmaking forms that draw on traditional techniques for engraving treasury notes to etch portraits onto these redacted poems.

Titus Kaphar, “A Pillow For Fragile Fictions” (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery.

And for “Suffering From Realness” I’ll be exhibiting three sculptures in the exhibition, three large-scale paintings and a few other works. Each of them is dealing with this issue of multiple narratives. One of the works in particular, a sculpture I did a little while ago called A Pillow for Fragile Fictions (2016), which is blown glass in the mold of George Washington’s bust. The glass vessel is about two feet long and three feet high. Because it is hand-blown glass the figure of Washington is distorted. The piece started out after a friend read this book about George Washington and his relationship to slavery. To summarize the narrative, Washington had become sick of this one slave continuing to run away. So Washington decided to trade this man for a grocery list of items: tamarind, rum, lime, and molasses. So in this sculpture, those elements are actually what are inside of the vessel itself, this distorted glass bust.

So the title of the show, aside from being taken from Jay-Z and Kanye West’s song “Ni**as in Paris,” is also in reference to a quote by Elaine Scarry: “It will gradually become apparent that at particular moments when there is within a society a crisis of belief…the sheer material factualness of the human body will be borrowed to lend that cultural construct the aura of ‘realness’ and ‘certainty.’” Do you speak to this idea of using the body in moments of crisis to show truth or “realness”? And how is the body incorporated into your work as a whole?

The way that quote speaks to me is thinking about how certain bodies have been erased or ignored, and never included in the proverbial composition. My inspiration for that quote and conversation I’ve had with Denise [Markonish, curator of the exhibition at Mass MoCA] really speak to that aspect of it – these real bodies that have never been fully considered. These kinds of bodies, by and large, were meant to be stand-ins for a symbol of the economic wealth of other bodies in the history of painting. We could talk about black bodies, we can talk about transgender bodies, and we can talk about the female body. That’s what I think is really great about this exhibition itself. Denise has created a space for all of us as artists to be able to engage this subject in a way that feels honest to us, and doesn’t feel like something tangential from our practices. To me that’s what makes her a great curator. She has this way of putting parentheses around an idea without inhibiting the creativity of the artists who participate in her exhibitions.

This article was originally published in artnet News, one of our partners.

Titus is the mvp – happy it’s finally getting recognized on a higher level!

A very talented artist with a fresh approach to history past and current issues using painting as a vehicle. Very provocative approach