The artworld’s proclivity for travel requires little explication. Between biennials, fairs, historical pilgrimages, and emerging art destinations, the dedicated art viewer crosses continents to view work. And while this tendency faces frequent criticism for its decadence and emphasis on consumption, its impulses have found a new outlet in the rural festival.

This curatorial model has a few requisite components: a rural, but nevertheless heritage-friendly location; some urban artists working largely with video projections and installations; and marketing focused on attracting city-dwelling art viewers. In attempting to emulate the lure of large international events, rural festivals tend to also imitate their flaws. An insidious flattening occurs. With directives to view vast amounts of work in a short time, the overriding edict seems to be art by attrition, and any insight into the hosting spaces get truncated or cheapened.

At their best, rural festivals can offer meaningful bridges between communities that frequently seem at loggerheads, or simply overlooked. At their worst, these models boast a prelapsarian escape from the vulgarities of a high-turnover, publicity-oriented international art system, hinging on their same characteristics of impermanence, mobility, and lack of specificity. Good intentions aside, these ventures issue an uncomfortably Richard Florida-esque mentality: the belief that, regardless of context, all locations are made better, or more profitable, through art. But there are limits to culture’s improving effects. At some point, shipping-out artists, art institutions, and art viewers encroaches on homegrown cultural imperialism.

The rural-festival model recently effected a sound application in Sunday Drive’s Warkworth project. Two hours northeast of Toronto, Warkworth is a picturesque village known for its maple syrup, rapid gentrification, gay population, and, oddly, jail. On a Saturday afternoon in late August, two buses full of Toronto-based art visitors arrived to observe eight art installations and performances distributed around the town’s Main Street. (Livestock pavilions became basketball courts; out buildings subbed as white cubes.) Helmed by Tania Thompson, Sunday Drive programs “arts events that bring new audiences to new places.” The purpose in bringing these audiences to new places, though, remains unclear.

Warkworth’s overall structure largely relies on the “ambulatory consumption” that characterizes larger biennials (to borrow the phrasing of New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl). Video projections and installations occupied visitors, briefly, before they moved on to the next space. A few works captured more attention, or at least retained it longer: Oliver Pauk and Michael Vickers’s Spectra Logic, for example, which hung reflective shapes in and amongst trees at the creek’s edge. Occasionally catching rays of sun, the piece was visually captivating. Also generally lauded was Karen Abel’s Riffle Pool Riffle (Mill Creek), which covered the floor of a small wooden building with glasses of water drawn from the nearby creek. These were divertingly pleasant projects. Simple and elegant as they were, though, an integral element of intensity was lacking from each encounter.

When works resisted an easily-consumable format, they were met with less enthusiasm. On Sunday, after the buses had departed, a piece by Duorama, a two-person performance art group consisting of Paul Couillard and Ed Johnson, began in the afternoon (simply titled Duorama #119). The sheer physical demands placed on viewers were challenging: no seating, mid-day sun, and late-August heat. Throughout, Duorama repeated for several hours a series of minute and inscrutable gestures. They played a card-game war, took two jackets on and off, dipped them into a mixture that appeared to be concrete, and later attempted to wipe the garments down. Two hours into this process, there was no audience to be found. Difficult artworks, ones that resist or challenge their viewers, are not inherently superior to the readily digestible, but they can offer a productive counterpoint to the lulling, sometimes numbing, effects of the festival model. Without a viewership, though, these efforts are made futile.

Audience engagement aside, even the strongest and most popular works presented through the Sunday Drive project said nothing about Warkworth. Viewers returned to the city with scant knowledge about the region’s existing cultural touchstones, which seemed largely removed from the weekend’s happenings. Visitors had simply traveled to a microcosm of Toronto, momentarily shifted into leafier, more placid surrounds.

While the model has inherent flaws, rural festivals can find more successful models. A good example can be found in the 2013 exhibition Land|Slide: Possible Futures, curated by Janine Marchessault. Located throughout the Markham Museum, an open-air institution that comprises nearly thirty historic buildings across an acreage of land, the exhibition focused on themes of “multiculturalism, sustainability, and community,” which were presented as key elements of Markham’s past and future. (“Suburban festival” might be a more apt descriptor for this project’s location.) Much larger in scale than the Warkworth event, Land|Slide undoubtedly benefited from a bigger budget, more time, and all the benefits these resources afford. However, Land|Slide also possessed a level of research and site-specificity that elevated, rather than caved into, the rural-festival model from which it stemmed.

Even when contributors shared little history or personal connection with Markham, the exhibition’s art elucidated and connected to its specific location. Deirdre Logue’s Euphoria’s Hiccups (2013), for example, incorporated the medicinal, healing elements of honey and herbs produced in the Honey House, where her work was installed. These types of connections and collaborations take time, research, and resources, but are effective in helping the artist avoid patterning mere touristic marketing.

The rise of rural art festivals should come as no surprise. At present, statistics detailing attendance at art events lay bare the public’s desire for blockbuster exhibitions and experience-driven programming. It seems logical, then, that smaller projects would attempt to recreate the sensibility in which these spectacles trade. If it worked for Venice or Kassel, surely a smaller, domestic version could only benefit Warkworth or Markham? This optimism, unfortunately, rarely gets manifest. Rural festivals have potential, but if they continue hewing to the global artworld’s high-visibility models of temporary engagement and momentary satiation they do a disservice to their art, audiences, and locales. They offer the peripatetic in lieu of the profound, and tell us that art needn’t be of a place, but merely somewhere.

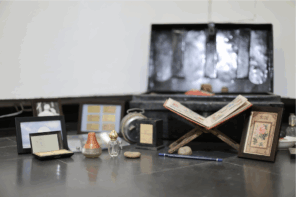

Image credit: Patricio Davila and Dave Colangelo, “The Line,” 2013. Video Installation.

While Morgan-Feir makes some interesting points about destination based art, I think it’s problematic to write about the tropes of rural art festivals when only using two examples near Toronto as evidence of their failings. Looking at rural art festivals in Atlantic Canada, you can see stark differences to what she describes as “prelapsarian” and/or not fully engaged with its context.

Certainly, places that have a focus on international recognition like Fogo Island can fall into the trap of parachuting in international artists, but take for example the Bonvista Biennale which has been building up a culture of art appreciation within its rural community using while challenging its audience (Pepa Chan, Will Gill etc.). You could also look at White Rabbit Arts festival in Upper Economy, NS (“Escapists and Jetsetters” cover article of Cmagazine, 2013), Mary MacDonald’s curatorial practice focused on rural community engaged practices including the W(h)ere festival in Pictou, NS, the Antigonight festival in Antigonish, NS or Uncommon Common Art, a road trip style summer long festival of installations in Kings County, NS both reviewed in Canadian Art for the success of their site specific works and community engagement.

Maybe it’s that the urban art centres on the East Coast of Canada aren’t as separate from their rural contexts, or maybe it’s the scale of engagement that allows artists to build meaningful connections with neighborhoods here, but I think to undermine the value of rural arts festivals with such a narrow focus does a disservice to the work artists are making outside of the urban art centres.