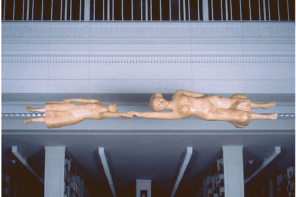

Milling through the Vancouver Art Gallery earlier this spring, I stopped before a towering diptych that paired a cartoon prince and a back-turned nude. The prince’s face has been whited-out, but familiarity flickered through: a blown-up reproduction of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Petit Prince. Similarly, his counterpart, a grainy portrait of a prostitute by E.J. Bellocq (c. 1912), had been extended and partially scrubbed out. But where she was still performing her role – her backside broad, classically profiled, pear-shaped and inviting – the prince affected a citation: how did I know him? And, now, here, like this, what did he mean? The prince made a footnote, but the anonymous (and visibly erased) female form was its own site of desire, a place to pool want. Looking up at La blessure d’une cicatrice ou Les Anges (The wound of a scar or the angels, 1987), by Geneviève Cadieux, I was reminded of the artist’s stature in the 1980s, and the lasting power of her commentary. One can still be awed by her currency and concision, her deft application of charged signifiers, postmodern puncta, and her insistence on the photograph-as-object. Her ellipses are loaded, her literary references, eliding. And though the work has appreciated in the thirty years since, it has also sagged with applied readings (the notion of “thwarting of the gaze” fairly hangs on her lens). It’s also grown taller and more impatient as we re-tread tiresome inequalities. I felt this acutely as I listened to a self-assured man introduce his date to the piece and proclaim that “nobody knows Quebec artists outside of Quebec.” He seemed to have missed Cadieux representing Canada at the Venice Biennale in 1990, or her recent Prix du Québec. I stood a while longer, translating a phrase inscribed in the work: “Here is the best portrait that I was able later to make of him.” I thought of the time lapsed between the complex moment of the work’s first framing, and the tired sear of the image now.

Geneviève Cadieux, “La blessure d’une cicatrice ou Les Anges (The wound of a scar or the angels),” 1987. Collection of Vancouver Art Gallery.

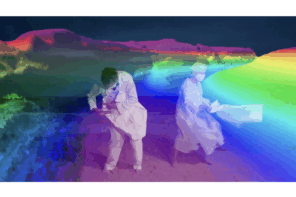

Weeks later, I paced a solo exhibition of Cadieux’s new show in Montreal. Her prints still loom and pitch and require long reading. They’re too big for a glance. But it seemed that here, in the spare, luminous rooms of her long-time gallerist René Blouin, the artist had shifted from body-as-polemic to what Barthes termed the “pleasure of the text.” Through a series of portraits featuring the exhausted landscape of the New Mexico desert, Cadieux allowed herself to inhabit the corporeal, less as a vessel for introspection than a light tower from which to look out.

Ghost Ranch features massive, lean-to photographic prints that are starry, swimming, and alchemical. Focusing on a terrain famous for artistic self-exile and inquiry, Cadieux captures a famed tree that enraptured Georgia O’Keeffe. (Apparently visiting artists now have to pay to produce work on these grounds. It’s one thing to look; another to keep the image.) In our roaming conversation, Cadieux cited as inspiration Japanese Ukiyo-e paintings (those whirring cherry blossom trees, their forever horizons, their prolonged now), and unselfconsciously referenced Van Gogh’s celestial augury.

The peaceable focus and plain affect of this series might suggest a tumbling-down from the sharp peaks of Cadieux’s zenith. But her attention to earnest landscape isn’t new. In 2002, she focused on a solitary tree, a lonely survivor of Montreal’s 1998 ice storm. In more recent years, she’s produced enveloping, near-abstract prints of rippling, horizon-less waters, which she then traces with silver leaf by hand.

In Ghost Ranch, Cadieux draws us into the experience of searching the spotted skies of the arid Southwest with nearly no utterance. The silence is marked, but our body still becomes magnetic. Art historian Thérèse St-Gelais once reflected on the “summoning” in her work. “Cadieux’s art is one of distance. It pulls in at the same time as it pushes away; everything here evolves around neutrality and involvement, perception and visibility.”

Pulling us close, reminding us to inspect, Cadieux limns her prints with delicate silver and gold leaf, and traces each sand ridge, each point among the stars. She allows light to shine through, but pivots and then expels this reflection back. An illustration of the photograph’s malleability, its potential for fiction, carries her charge. But there is a drifting quality to these images. Where once she zoomed in on the foresting of a pubic mound, the urgency of a moving mouth, or the central site of a body’s scar, Cadieux now turns her lens out and slows its shutter. I ask her if these timeless subjects represent a refusal or a turning away from present-day crises and anxiety. She seems unmoved by the question, and says, simply, “you feel landscape more as you get older.”

We walk towards the door, and I reflect on a female artist entering her third age, no longer excavating her body and arguing for its position, no longer agitating from the limits of her lens. Cadieux, though still playful in her medium, inhabits her form confidently. She appears to be calmly looking out. We pass Blouin, who is sweeping – a legend in his own right, forever fastidiously dressed. He is bent over a straw broom and a metal pan. Cadieux laughs. “Thirty-five years later,” she says, “and it’s still the same thing.”

With thanks to my mother.

1 Comment