Hadar Kleiman’s brainy, seductive solo show at R/SF Projects in San Francisco reproduces sites of pure consumerism in a playful, complicit kind of late-capitalist Arcades Project, dressed in gaudy Vegas neon. Rather than exploring a particular locality, as with Benjamin’s historical covered shopping passageways in Paris, Kleiman resolutely pursues situations of placelessness and locations that could be anywhere: malls, casinos, airports. The spiritual seat of Premium Emporium might be a duty-free perfume boutique at a run-down international airport, or the worn paths of desire running across a casino carpet patterned to hide stains and cigarette burns. The show critically examines the mythologies of value and power that underlie such nondescript yet aspirational places where spending money is the main attraction.

Its literal location, of course, is an art gallery: another altar of conspicuous consumption, but one where few will buy and the rest of us are only window shopping – a trope that Kleiman takes up quite literally. What we are browsing for, exactly, runs the gamut in Premium Emporium, from our basest desires, to more abstracted fantasies of wealth and class, to spiritual hopes for deep connections with history and the mystical realm. The show gestures toward long cultural histories of consumerism that take our impulses to spend seriously; all consumer spaces, Kleiman ultimately suggests, de-temporalize classical visions of beauty and strip them of character.

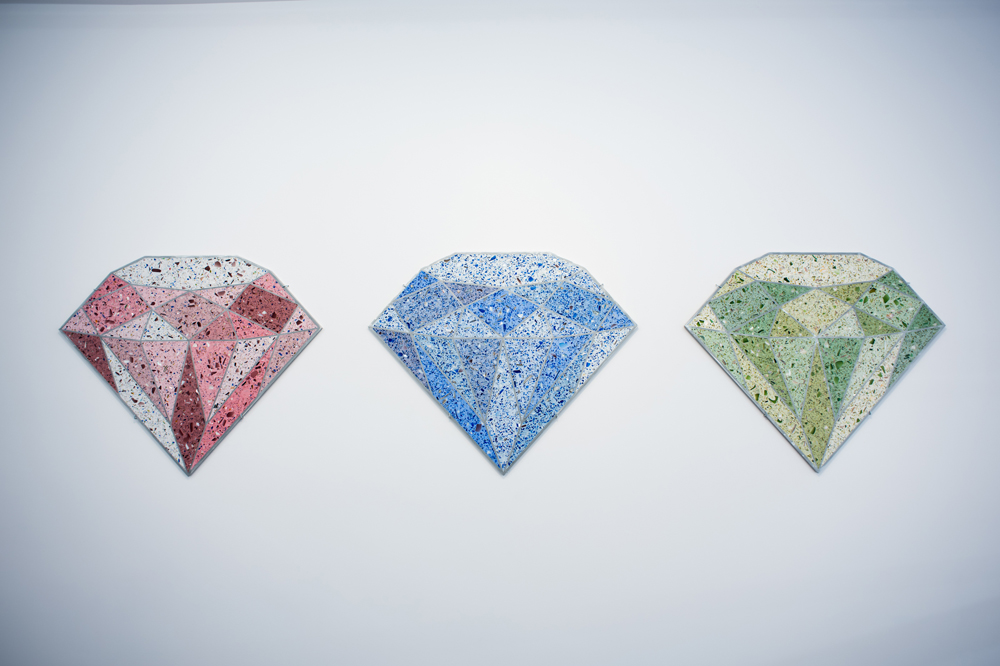

The visual language of the exhibition reads clean and fresh at first, its sculptures and installations packaged in the familiar Tumblr pink and gold accents of post-internet merchandise. Displayed in glass vitrines, elaborate gold frames, and – in one case – a replica of a department store window display (Mall Wall, 2016), Kleiman’s pieces lure with their bright colors and tasty suggestions of base desires: sculptures that look like dildos, wall pieces made of candy-like terrazzo flooring material, a crystal skull that, in recalling Hirst’s famous line regarding his diamond skull – that his medium is money itself – signifies simply price itself. Right away, the show colludes us with our own attractions to things. One wants not just to look at and touch Kleiman’s work, but to eat it, to screw it, to cash-in.

But the work is more than a body of degraded objects. For one thing, Kleiman ruthlessly points out how the backend machinery of desire works, especially in the dominant installation Mall Wall, which sprawls in all directions beyond its store window display, with particleboard flooring and half-built walls covered in artificial laminate. Mall Wall quite literally shows the back of its own machine, with visible clips holding in place curtains and the lights trained on the storefront. Inside the display case, tokens of wealth quickly reveal tangible cheapness: the crystal skull is artificial purple, the marble bust, an impossible bright blue. Many of the other works in the show operate on a smaller scale but employ the same visual rhetoric as Mall Wall, offering themselves up as both coveted objects and staging-sites for critique. Kleiman diffuses humor throughout this scene, as in If the Tooth Fits (2016), which proffers a giant sculpture of teeth sitting on a bar stool, seemingly ready to chomp into some instant gratification. The art itself is hungry for something to consume.

Kleiman repeatedly uses eye-catching, saturated color in combination with cheap materials to frame and amplify gestures of exorbitance and appraisal in places where everything is for sale. She seems especially interested in what lies beneath our feet: cheerful printed carpet from a Vegas casino; the recurrent terrazzo flooring. Such materials cover up cheap construction, as do the gilded glass tiles that adorn one of Kleiman’s two pyramid sculptures. Signals of value in tension with shoddy, chintzy components permeate the show, and Kleiman offers up the most vulgar objects and substances for contemplation: gaudy fake flowers arranged with ribbons and seemingly destined for a trash bin (Prom, 2017); an abundance of lurid gold frames; even an accent nail, that glaring class marker (Sephora, 2017). The adjectives suggested by these objects betray their own chintzy nature, just as describing something as “premium,” “fancy,” or “classy” often conjures the very opposite connotation.

A line of criticism examining fantasies of wealth and status could easily become a project about aesthetic displays as class markers, and the way that they collude with larger power dynamics and social positioning. These hierarchies have high stakes, and Kleiman at times seems to be engaging with Bourdieuian explorations of social strata. But ultimately, Premium Emporium is less interested in class than in deployments of classicism, and especially the way that they operate in elevating our affective experience of art window-shopping into an intellectual and spiritual realm.

Classical references are everywhere here, though their relationship to time is uncanny. Temporally, Premium Emporium sets itself both slightly out of our time, when department stores (less “brick and mortar” than plaster and melamine) and malls are on the decline; it also sets itself even more strongly out of any particular time at all. None of its cultural references are in any way substantially modern: fertility statues, precious gems, snakes in the garden make up Kleiman’s carefully nonspecific anchors in the deep past. Vegas, with its Luxor pyramids and Caesar’s Palace, is privileged as a site where classical visions of value and beauty float like conceptual balloons, marooned from their original context. Here flowers, columns, monoliths are trotted out like tired old talismans that have lost their powers of value-addition.

Somehow Kleiman manages to make these symbols’ power potent again in the smaller upstairs atrium gallery, where the show moves from the realm of literal consumption and into one of myth and magic: objects that persuade us of their link to some kind of higher realm. On the far wall, the terrazzo appears again in the form of three diamond icons on the wall: “you may have already won!” Two deeply alluring pyramid sculptures dominate the space. One is hidden inside the aforementioned tooth sculpture, which turns out to be a façade; a coiled snake ready to spring waits inside, in a diorama-like Edenic space lined with mirrors and piled fake leaves on the ground. The mythological realm, Kleiman seems to suggest, lurks inside even our most basic drives to consume. The gold-topped Pyramid (2016) is covered on all sides by a worn carpet gleaned from a Vegas hotel, which is patterned with serpents, diamonds, and palm trees. The mash-up of ancient mythology and tourist-trap simulacra somehow convinces: even as we know that the artist is pulling our leg with tacky, rubbishy versions of our oldest symbols and shrines, it’s hard not to feel a symbolical and even metaphysical pull toward them. Kleiman’s deepest point lies in how this sleazy trick somehow works, even when it repulses us.

How Kleiman convinces, and what she persuades us of, comes out of the subtle, deep institutional critique of Premium Emporium, which takes on a world in which everything operates on the logic of Vegas: vulgar and hollow, atemporal and bizarre in its appeals to various levels of abstracted value, and based on our immanent consumerist gaze. In making the trappings of cheap wealth permeate a world of set pieces in a gallery setting, she stages this scene over and over at various levels of fantasy. What makes Premium Emporium fascinating is that even as it criticizes this position, it’s also complicit, both by the fact of its presence in a gallery, and in the intentional seductiveness of the work itself. Kleiman’s logic dares us to collapse the difference in the way we understand our desire for cotton candy and a gel manicure, and our desire to be led by art toward the numinous.