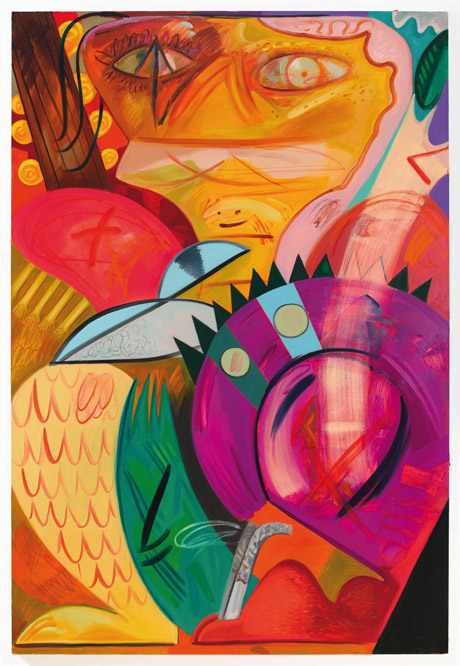

When I meet Dana Schutz amidst the clash and clatter of the installation of her solo mid-career survey at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, the artist has just overseen a re-hang of the third hall of her paintings. The three largest canvases – each more than eight feet tall – had been laboriously removed from their commanding position on the longest wall and reinstalled at opposite ends of the room. Teetering on the brink of abstraction, the eccentric and lushly painted portraits of godlike beings have a slight air of menace to them, tempered by an almost tropical palette. “These paintings were meant to be shown all together, in a line,” Schutz tells me, almost apologetically. “But you just went straight to them, and didn’t look at anything else.”

It’s an enviable problem, and one that helps explain the meteoric rise of the Brooklyn-based painter: her work demands your attention. Schutz garnered international acclaim in 2002 with her MFA exhibition Frank from Observation, which earned her a spot in the 2003 Venice Biennale, but in the intervening years she has reinvented her practice several times over. For Schutz, a painting is a proposition – a means of subverting a normative action or envisioning it anew. She builds narrative worlds around colorful questions, re-imagining the mundane in a thoroughly grotesque manner. A typical exercise might be: “How would you paint the last person on earth if you were the second-last?” Or: “What would it look like to smoke, swim, and cry simultaneously?” Though seemingly simplistic, these questions yield a host of pictorial and existential quandaries, which Schutz tackles with apparent ease and an extreme style of figuration that could almost be mistaken for abandon. Her actual process, however, is both considerate and intensive, manifesting a profound engagement with art history through smart references to artistic movements spanning the 19th and 20th centuries.

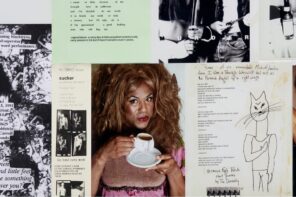

Her oeuvre includes a pantheon of sleazy gods, a civilization of self-consuming cannibals, a murder of politicos, a lonely survivor, and miles of sandy beach. Bizarrely proportioned and often frenetic, Schutz’ s figures somehow remain charming, even empathetic, and peculiarly beautiful. It’s work that feels risky, thinks deeply, and looks exhilarating.

Your body of work has obviously proven very idiosyncratic – you take a lot of risks, and make a lot of changes in your process. Was Breeders (2002) the genesis of that project of experimentation?

I’m always reacting to the last painting I made. Every painting could be a problem-solving issue. I definitely learned a lot about what I struggled against with this painting – what I could take, and how to put a painting together.

I’ve heard that you’ll mix a lot of paint before starting a work – sometimes 50 colors up front. Do you set parameters for yourself to work within?

I like working really early in the morning, or late at night, so I don’t know what time it is. I can just mix paint for six hours. I’ll have an idea of what kinds of colors I’ll be looking for. Sometimes I just listen to a book on tape and mix, like a long car ride.

Considering your body of work chronologically, the early work depicts an explicit, visceral violence, while the later work shows a more implicit kind. Like the Gods series (2013), which comprises some of your more recent painting, reminds me so much of Willem de Kooning’s Women. They all have these intense diagonals and a sublimated aggressiveness, a threat of violence. They’re so sleazy.

I love the Women paintings. I think they’re incredible. They’re like storms. Coming into a museum and seeing one, it seems like you’ve come across a wild animal in the room. I was trying to think of each one as an individual person, but they read more like abstract situations than portraits. I thought [God 5] could seem like Liberace, like a lounge singer – although that’s a little sleazy too, now that I think about it. There’s this collision between his body and the piano, like he’s sliding into the picture plane and the piano is being shoved back.

Are you pulling out some implicit violence in the subjects, or is it a byproduct of the situation?

Well, for example, with [Flasher (2012)], I wanted the feeling of the person’s face to be pressed up against the surface of the painting, which could be a violent action. I wanted it to feel like a painting that turned itself inside out. You can see its seams, and the coat is the color of canvas.

The compression of space in your recent work – did that come out of the printmaking you did in recent years (for New York print gallery Two Palms)?

I think that came out of drawing. I’ve been drawing a lot recently. I’d be trying to structure a subject onto the predetermined format of the paper, and it would be awkward to get it into a particular shape. I was making a lot of trajectories in the drawings to get the subjects to fit, and that really caused a lot of compression in the paintings, too.

Is that where the sharp lines come from? The trajectories that you’re delineating?

I think so. When you’re drawing, you can feel when it has the right composition. Composition seems so dull, but I like to think of the way you have a physical presence in front of a painting. So much about that includes a kind of balance, so you can feel the way that something is structured in your body.

There’s a compression of time in the newer works, too. They’re so right now, in the moment.

A lot of them are performers, or people demonstrating something within the painting, whether it’s a song, playing the piano, or just making the mark, like in Shaving (2010).

Does that mark relate directly to the painting of the work, as well?

It’s the indexical mark of the painting – actually, removing paint.

You’ve said you plumb art history as a kind of material for your work. How do you know when to use that material?

It depends. You make associations even while you’re painting, or in the initial idea, when you’re figuring out the structure of it. I don’t think it’s ever discrete, like a standalone reference. I think the way that references work now is that they’re all fluid. There are certain paintings that have a kind of logic to them that seem like they’d fit the subject. But there are other images in the world that could do that too. But I love looking at other paintings so sometimes they do come from there.

Is it the paintings that you love that end up in your work?

Sometimes. Sometimes it’s easier to deal with things you don’t like, that rub you the wrong way, that irritate you. There’s this challenge to get it to work. For example, Philip Guston made this painting of a dog eating garbage, and it’s the most annoying painting, it just makes me want to make a painting of it. I really want to see it again. Maybe I’m overstating this, but every painting has its own DNA – it has hints of previous works, but it ends up being its own thing.

Does what you’re looking at make a fundamental difference to what you’re painting at a given time?

I don’t know that it necessarily make s a huge difference. Sometimes I know I want something, and I’ll look for it. I was looking at some of [Jean] Dubuffet’s drawings because I wanted to do this kind of pattern-y field at one point, and I don’t really have the patience for pattern and detail. So I look at how other artists do that.

You flirt with abstraction, but you never go the whole way.

I need a subject. That’s how I understand the painting. I think that sometimes the initial impulse comes from an abstract notion, but I always go back to narrative information, even if it’s just cause-and-effect. There always needs to be some kind of thing in the painting, an object or person or situation.

I appreciate how in so much of your work there’s an invitation for a seemingly obvious reading of the painting, but the ease of that initial interpretation creates a moment of doublethink – you guess again. It kick-starts this process of reflection. How do you anticipate your viewers approaching your work?

Usually the hope would be that the painting could open up into something more. Some subjects lend themselves to that. For example, Getting Dressed All at Once – how do you paint that? The only way it could really work would be with that eye-contact with the viewer, and a hand against the back plane; moments that stop the action, that grant access to the viewer to what’s going on.

How do you feel about the contemporary direction of painting, the prevalence of minimal abstraction? Do you think online reproducibility is key to the success of a contemporary painter?

I was thinking about this recently, especially with [regards to] sculpture. Sculptures that look like something found in the street that you look at and say, “This would make a great Instagram photo.” It feels so ephemeral. I think what’s more important is how it exists in a physical space, when you’re standing in front of it. Of course paintings are physical objects, but images really have no body, no size. I want my subjects and paintings to feel like they have a space in front of the picture plane, that’s a specific physical interaction with the viewer. I’m not against them having a digital life on the internet – that’s exciting, too, and that’s how most people see images. It’s just harder for images to live and have presence in the digital realm.

2 Comments