No one likes being called an amateur, a dilettante, a dabbler.

“Unprofessional” is an easy insult.

The professional always makes the right moves, knows the right thing to say, the right name to check. Controlled and measured, the professional never fucks the wrong person or drinks too much at the party. They never weep at the opening, never lay in bed for days too depressed, sick, broken to move. They say about the professional, “so easy to work with” or “so exacting but brilliant.” The professional takes advantage from every encounter, employs every new acquaintance as a contact, always hits the deadline. When asked about their work, they know what to say, a few lines of explanation sprinkled with enough filigreed intrigue to allude to abysses of research, the mysteries of making. They answer emails in minutes. Their PowerPoints are super crisp. Look at their website, so clean, so modern, so very pro.

You don’t feel like any of these things.

You are hungry, tired, overworked. You drank too much at the party and then slept with the wrong person, and then the really wrong person. You missed the deadline, it just thrushed past with a whoosh. Hustlers around you disappear into wealth and fame. Your dealer tells you to make more with red, those red ones are really selling. Maybe, she says, you make only the red ones for a while? Your student skips class to go to an art fair. The most pressing collectors are the ones holding your student loans. They keep calling, you wish you could trade them a drawing. It can take days to answer the simplest email. Your website, if it exists, is in shambles.

You wander. You doubt. You change styles, media, cities. You experiment, you fail. Again. And again.

Unprofessional most literally means “below or contrary to the standards of a paid occupation.” Who makes the standards? Is everyone paid? Fairly? Is being an artist a job or something else? Who sets these standards? Do you wish to be standardized?

Art and success.

So easy to cocktail those two words together into “professionalism.” Pull up a famous artist’s CV and work from the beginning. Does success look like a sculpture plunked outside the Palace at Versaille? Is it a biennial, a prize, a blue-chip dealer? Is it the cover of a magazine, a thick, chunky retrospective catalogue? Even more evasive things just glanced, the luxury sedan like a bullet, shiny and hard, that the aging photographer bought after he dumped his smallish gallery and long-term partner, for a bigger dealer and a younger girlfriend, shiny and hard as his car; or perhaps, the off-hand mention of a domestic servant, a personal chef, the third nanny, the smallest chink in the opacity of wealth, so very far from the roaches scurrying in your kitchen sink and the fact that you’ve eaten nothing but mushed pumpkin and cigarettes for a month.

This did not feel professional, but it’s true. These things you experienced to be an artist.

Your body of work is a mark of your passages, the richest of your thoughts and the deepest of your emotions. Simply manifesting this into art is hard enough, but today you feel like you need to be professional. The pressure and penury makes you nervous and cautious. What can you make that will take the iron of poverty from your flesh, that will make this feel less like a terrible mistake?

Can’t you tell by my clothes I never made it

Can’t you hear that my songs just won’t sing

Can’t you see in my eyes that I hate it

Wasting twenty long years on a dream.

Lee Hazlewood, “The Performer” (1973)

Somehow making money makes us feel for real. Money we can trade for food and shelter, for time and space and materials to continue. These things are hard and pressing, but it’s not the money that makes us real. We are real already.

Everyone can be an artist, not because they have a degree or they sell, but because they live life artfully, with skill and imagination, freedom and awareness.

But artists trade promissory notes and subsume authority into institutions for some outside validation. Proof to your beloveds they weren’t crazy in supporting you financially, emotionally, spiritually. Later, broke, you exchange dreams for money, or even, later yet, make other people’s dreams and trade those instead.

Collectors, they are really responding to the red ones.

The path is clear for the professional. BFA, MFA, Commercial Gallery, Museum. 5 Things Every Artist Has to Know About Getting a Gallery. 10 Easy Tips for Killing Your Studio Visit. 3 Totally Simple Steps to Art Stardom. Mix in a teaching appointment perhaps, a grant here, a residency there.

For the unprofessional, it isn’t so narrowly defined. As Charles Bukowski wrote, the shortest distance between two points is often intolerable.

It’s not that artists shouldn’t be paid for their labor, but we ought to refuse the assignation of value and worth purely based on salability or the validation of institutions. Systems will always seek to swallow us. We must resist the efficiency of their gears with the softness of our humanity. Unprofessionalism is asserting our right to be human against this machine.

Fragile, weak, doubtful, bumbling, to be “unprofessional” is to simply be human. This does not mean acting without ethics, honesty, or basic kindness. These finer qualities can easily exist independent from how we trade our time for money.

Professionalism makes a person into a brand. The cynical think this has already happened: our slightest movement tracked for personalized advertisements, our declarations and photographs that we share with others all branded and branding, self-awareness as commerce. And though others can attempt to professionalize you, reduce your spirit to a slogan, a product, a logo, you do not have to do this to yourself.

For the time being we live under capitalism, but we don’t have to be broken down into its systematic alienations, divisions, inequalities, reductions of all value to market-value.

In some ways, I was piqued to write this by Daniel S. Palmer’s recent essay on hyper-professionalization just published in Artnews, which ends on an inspiring note: “In a moment of monotony and conformity, artists must reclaim their freedom.”

He opens his essay with a young artist pitching a practised spiel, surrounded and over-handled by art pros. This fails miserably to impress Daniel Palmer. Obviously, being a professional in this sense doesn’t always work. It might have currency with those who are also hyper-professionalized like this particular emerging artist, churning through a system crafted for exactly such purposes. But it didn’t work with Daniel Palmer, and it wouldn’t work for me.

Such clear professionalism is crass, careerist, empty. Repulsive even. “Ambitious young artist” always sounded like an insult to me.

I see making art as the necessary expression of the human spirit. We all need to live, but when the acquisition of wealth becomes the primary endeavor, you are no longer an artist but a financier.

More than a gallerist or a manager, a dealer or an advisor, a critic or a curator, more than an army of assistants and a clutter of collectors, an artist needs the courage to act alone and a community that makes such acts more bearable. One that allows us to be vulnerable, inappropriate, to go rogue, go wild, act weird, and fail.

To be amateurs, dabblers, dilettantes.

An amateur is filled with love beyond compensation, the dabblers fearlessly go places they don’t belong, the dilettantes happily lack the hidebound pretensions of experts. When we step out of the imposed confines of professionalism, we can be as open as students, able to flirt with other modes, to seek knowledge, experience, and value in our lives without limits.

Stripped away of institutional validation and the pressures of the market, we are free to be human, to be artists, to be unprofessional.

This is a timely retort to the increasingly parsed out, segmented and specialized roles within the art world. The artist’s task turned into a job rather than appreciated as a vocation. Thank you, Andrew Bernardini for this concise, honest article.

Thank you for this. It is pure gold.

Excellent read, thank you.

I have a really had time agreeing with your article. You have to remember I come from a place with no formal education but I also come from privilege. I’m also a millennial that believes technology is radically redefining everything we know about art and design. Our generation is radically underestimating how much work is actually required to simply do better. Live better. Feel better. Think better. Do something better. People ask me all the time, what does it take to do what I do? I tell them, all them two words. Hard work. Hard work and that means doing it all. My father has always said to me, it’s not that you’re going to be okay, it’s that you’re capable of being okay. I asked him when I was younger, I asked him can I be an artist? He told me, yes. But you can also be an entrepreneur. You can do both. I find western philosophy and how people are raised here to be quite black and white. The idea that you are either sad or happy. Good or bad. Success or Failure. I was raised from a culture where we are taught, “Do what makes the family happy, and in turn should make you happy” Here people are taught “Do what makes you happy”. I don’t know whether or not my consciously taught me this but we are heading into a posthuman era where technology is becoming a verb not a noun. I think the point I’m trying to make is, you need to do both. You need to be professional and unprofessional at the very same time, finding the balance. Maybe that sounds like too much work, but it isn’t. It’s the future.

I resonate with this comment a lot. And I didn’t go to school, and I don’t work with art dealers, so maybe the world that’s being written about is just foreign to me. Reading about these things is kind of fascinating and it was a great piece. But I, like many friends, find myself vascillating between “professional and unprofessional.” In order to not work a dayjob I need to make money from my art, and the internet has allowed me to brand myself in a way that I’m happy with. Actually, I thrive on it! I still play, experiment, make heartfelt art, try new things, relax, watch a crapload of netflix, smoke weed, but I also make a (low but reasonable) income because I have a clean website and am reasonably prompt and can write a good email and befriend clients and don’t party too hard or sleep with the wrong people… and that feels great! It’s empowering! I think finding an in-between spot is a good, liberating place to aim for.

Does smoking weed make you professional or unprofessional? I like cocaine and MDMA. Where on the spectrum do they fall? I imagine cocaine to be slightly more professional than MDMA, right?

“The path is clear for the professional. BFA, MFA, Commercial Gallery, Museum. 5 Things Every Artist Has to Know About Getting a Gallery. 10 Easy Tips for Killing Your Studio Visit. 3 Totally Simple Steps to Art Stardom. Mix in a teaching appointment perhaps, a grant here, a residency there.”

This statement resonated with me resoundly, because I was once on that path. Railroaded, almost, graduating from a design-focused high school in 2007 (just before the economic crisis) and sucked into the education-career pipeline. It took me almost 5 years and lot of grant money to fail gloriously and be told that I was “too much of an artist” to become a designer (I was a prospective automotive designer)

Yes, college (or higher educational institutions rather) are not for everyone. I didn’t come from privilege. I didn’t come from an enclave of wealth. What I discovered that it takes a harmony of three factors that must come together in the way of the artist: the tools, the technique, and most importantly, the talent. Ever since I was 4, I found a voice through visual arts and going through formal education did that natural talent sharpened and I became familiar with expert tools and techniques that helped me do what I was already doing with my talents more effectively.

Wow, Adrian. Very well put. Silence.

Good comments. I play music for a living. There is always a conflict between charging money and contributing to the community for no money.

The first pays my bills, the second establishes me as socially valuable. Both are essential but the first is difficult while the second is easy to do.

Thanks all for the really kind words.

I’m sincerely moved with gratitude for your reading.

One thing I’d like to address that seems to keep coming up in some of the online discussion out there is the idea of hard work, as if this is a paean to laziness. Whilst I have nothing particularly against laziness, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, Marcel Duchamp, spent a good portion of his life simply playing chess. Larry Darrell a favorite character from Somerset Maugham’s ‘The Razor’s Edge’ called it ‘loafing.’ But what appears to laziness to others (all of Larry’s childhood friends and family complain that he’s wasting his skill and talent in not getting a job) is actually humans working really, really hard on projects that aren’t economically driven.

To paraphrase John Ashbery quoting Flaubert, it’s true some people labor very hard down the wrong road to art. Or that some might interpret soul-searching or contemplation as laziness, but as far as I can tell from my generational vantage point, my peers seem to be working really, really hard for way less than our parents and grandparents. (I’m sure you can imagine how laughably difficult it might be for me to feed and shelter my family writing this stuff, it’s not my pop’s union factory job, but he got paid a lot more than me.)

To put it more crystalline, we are working our asses off just not always for an almighty dollar and in ways that aren’t always as clear as more conventional forms of labor. I wish we could all maybe work a little less in general, but that’s another essay.

In terms of professionalism versus unprofessionialism, I’m sort of nudging hopefully in the direction of full consciousness shift for a lot of what daily existence means, one of those ways is breaking down modes that alienate us from ourselves, others, things, and our space/landscape, professionalism seems to me to be one of those modes.

Marcel Duchamp left the art world, as in stopped making art, to become a professional chess player. He made his first chess set by hand, and basically stopped making art. To equate Duchamp with laziness or loafing just because he rebranded a toilet at one point in his career is painting a very very very industrious artists with one brush. A walk inside the Philadelphia Museum will prove as much.

The problem more lies in a combination of late-capitalism having flood and ruined the art market (the process of professionalization as you identify it) combined with the newest generation of artists being able to disseminate their art immediately with the internet. Previous to last two decades or so, there were whole generations of artists who failed at being professionally successful artists in their lifetime, but somehow continued to work in hopes that someday in the future their work would be discovered. For instance, how many artists can you count that only achieved notoriety posthumously? How many millennial vapor-wave net artists do you know that would honestly be okay with making work in the shadows for their entire life?

The problem is somehow this generation, myself included, was duped into believing that if we worked really hard at what we wanted, we could make a living doing whatever we wanted. Art is unfortunately not one of those areas. To think that you should have your entire survival ensured because you really like the art you make is honestly a pretty selfish concept. Yes it is probably good for your personal well-being, but except in very rare cases it gives very little back to the community at large. Thats why artists used to be held in such high esteem, because it is very hard and very rare to make art that actually speaks to people, or is actually completely successful.

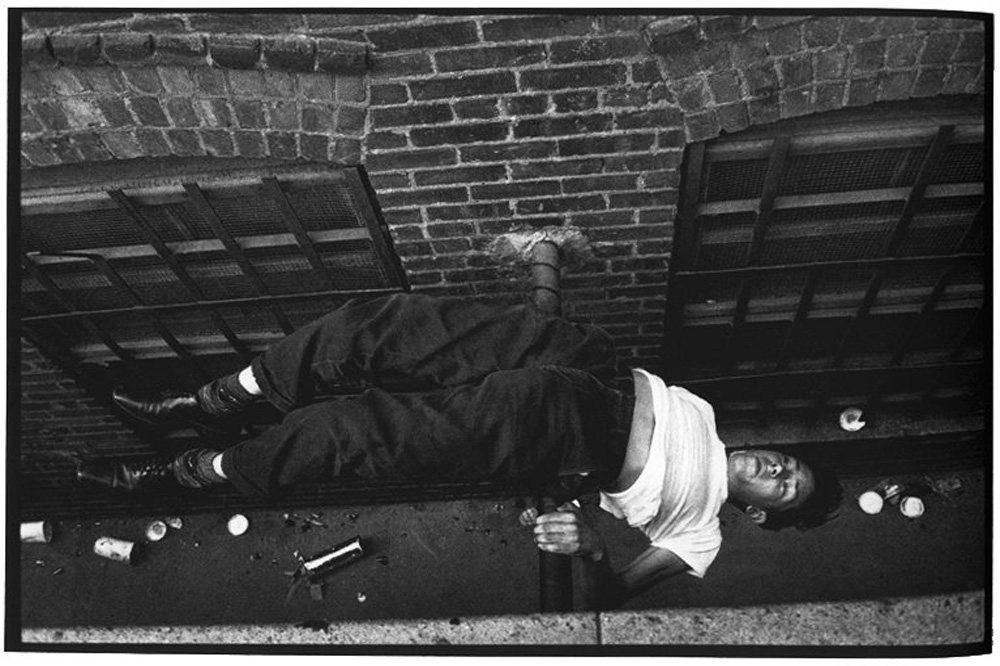

The problem I see today is that lots of people are drawn to being an artist because they like the lifestyle of a supposed successful artist. They want to be the toast of the parties, they want to be able to drugs and have sex without reproach. I think the image used for this article is a good indication of that. My worry is that in the democratization of art making we will throw out conceptual or intellectually based practices because they are seen as ‘too professional’. Then we will have ‘artists’ who will do nothing but create decoration for corporations to sustain a lifestyle.

For me being industrious and taking care in what you make isn’t the issue, the issue is that we expect notoriety and compensation immediately. To further encourage everyone to make art, and to put them on the same level as people who have devoted their life to making work then further exacerbates this problem. Sure its great to paint a pretty picture every once in awhile to make yourself feel better, but to call then call them Artists in the truest sense sort of slights everyone throughout the history of Art that worked really hard to hone their practice. Some people in previous generations literally drove themselves mad to satisfy whatever muse they had, and I’d argue it was they, not casual dabblers, that fearlessly went places [the art world] didn’t believe they [or art for that matter] belonged.

This is more pointed than I’d like it to be, but that is only because I enjoyed your article and it caused me to think more.

Excellent read! Thank you very much.

Thank you Andrew and Momus for sharing – I connected with your raw observations and have shared it with my fellow artist friends who struggle and starve to “find their voice” … sticking to trial, error and the voyage of discovery. It reminds me of the explorer who may never reach true north … and yet may so must not settle or surrender. Thanks again.

I’m a professional artist. I’m also a woman over 60. I up the anti on my professionalism but not in an obssessive way but I do stress it otherwise people think I’m available to do “stuff” as they think I don’t “work”. So I go to work at the studio. My gallery also sold all my works from the last 4 solo exhibitions to one client last year. 40 works went to Dubai, Abu Dahbi and Osaka. It was a freak out. My best work went but I got a wage for the first time in 30 years. It released me from even contemplating what may or may not sell. Everything I do has the possibility of selling so I no longer worry about that. I just do what I want to do. The sales gave me incredible freedom, as does the professionalism.

I liked your article it described me in the 1980s when I published and designed an avant guard magazine but in today’s climate if you aren’t serious about your art you’re not an artist.

i’ve been a professional unprofessional artist for years now. i earned an mfa from ucsd to study with allan kaprow… then i spent almost a decade working with niki de saint phalle… all the while being true and free as an artist… so much so that my art friends and colleagues don’t even recognize that i am an artist. i always hated the gallery scene and did what i could to thwart capital exchange… so you can imagine where that got me with gallerists and collectors. hah! duchamp retired to play chess… i retired to grow plants and talk with them. the art world is as overinflated as capitalism is hyper. i live art and i refuse to recontextualize it back into the shoddy world of art to gain some recognition. thank you for this piece.

So you didn’t try to sell your work…

How exactly did you expect to make a living from it, then??

80% working for 20% of specialized market, hard to be too serious in “professional” way; but art is intrinsically complex, disciplined, scientific, rigorous but also must “free” to contain, manifest, express shared meaning. Remembering a painter showing me a work he had spent years on with attention to technique and detail. My response was that painters don’t sell labor they sell vision, emotion, the “rightness” of the piece. Something apparently done quickly is not necessarily less valuable or noteworthy than something labored. There is a “science” of rightness above and beyond one’s own estimations, likely determined collectively given some exposure. Happy trails to all, you are the one walking it.

I am from Nepal. I am an unproffessional artist. I perform. Many people think that and tell me that I work at a radio station. But I don’t. I don’t do job there. But I host the shows. I am simply a host, but not as an employee – how I see myself from my inside out.

Thank you for this wonderful article. I will love to remain unproffessional ever.

Doesn’t pimping your bio kind of negate the premise of the article?

Word up

Can you please, in as few words as possible, explain the point of this article. I honestly don’t get it.

Should Artists Professionalize? Um, they already have, says Julia Bryan Wilson. But maybe they should reframe the question to “profess” what they believe in: http://buff.ly/1Ruc1tg

I agree with those who say that black/white thinking on this issue does more harm than good. The scene laid out in Palmer’s ArtNews article is appalling. But I’ve worked with hundreds of artists, across the spectrum of “success” as typically defined, and I’ve never encountered any situation this extreme.

The Lean In/Bootstraps model for artists is a frightening spectre, but let’s not forget how damaging the romantic idea of the artist as emotionally overwhelmed dreamer who “just can’t make it in this world” leads to a sense of hopelessness over things that are within one’s power to change (like who you go to bed with and how much you drink) that has caused not a few artists to end their lives, success be damned.

Taking reasonable steps to hone your skills or put your work in the world doesn’t make you a sell out or charlatan.

And while we are on top 10 lists. Here’s one (it’s 12 actually)

Checklist for Martyrdom:

drink a lot

sabotage your personal and professional relationships

wrestle with your creativity so vehemently that you end up bloody

express constant dissatisfaction with your work

jealously compete with others

begrudge the victories of your friends and fellow artists

attach your happiness to external rewards

be arrogant when you are successful

be self-pitying when you fail

honor darkness above light

die young

blame creativity for your early demise

Thx also a good and balanced insight…

Watched the video… “Yes”. Thanks.

I feel like I see this kind of article written repetitively. Because, it’s writing. For a company. In any case though, we can skip over the obvious institution rooted ideas that those that write these articles share, commonly. The line “Stripped away of institutional validation and the pressures of the market, we are free to be human, to be artists, to be unprofessional.” made me giggle, because that’s the exact place or origin that artists root from, pro, amateur, whatever. Because artists have the ability to act from that place, infiltrate a system, of govt or what have you, and operate harmoniously free. I think if one has a issue with this idea or does not understand it, the arts is a wrong path you have gotten stuck in, where you should not be, unless you have problems like this article points out. IMHO, that’s the break between artists and non, forget words like pro. Ps I am a pro.. But if your an artist, your happy, if not, you may just not be what your thoughts are telling you. It’s simple, does not need articles explaining the life of an artist so in depth. If you are one, you know, if you don”t know, then, well, sorry, and don”t get bummed out.. I know that I could not be a surgeon.. But I’m not writing articles about it or my opinion on the professionalism or non associated with that world. Cheers.

Thanks for an excellent read. I adhere, I agree with most of it.

I do however not understand this misconception that artists don’t need to sell their art to survive. Care to let me know how to pay my bills?

If you want to be a true artist – meaning not having to pursue some shitty dayjob you don’t care about – you’ll have to sell to survive. Do you have to make millions? No, but enough to have a roof over your head, food on the table and last but not least to buy art supplies.

So basically this article, albeit well written and to the point, doesn’t help me at all.

It’s basically the same stuff I’ve read and heard so many times without any real solutions on how the heck an artist can survive in todays art market.

I’ve been thinking about your article for nearly a month now.

It solicited my vanity so well.

I justified my hangovers with you and my pro-forma invoices against you.

Thank you for this. You nailed something here.

My thoughts in summation.. *Very good + Not, Glib

Thank you for this salve to my psyche. As I dig into a ‘transitional’ period of work I care for and defend my spirit against detractors, scoffers and cynics – real and imagined.

This article bothered me when it first came out and it still bothers me now. I understand the self-loathing that Bernardini is talking about, I recognize it because its the emotional detritus that all sensitive and creative people must wade through. My issue with the article is that it seems to promote the idea that if you are privileged enough to wallow in that emotional state because you are supported by generous people, you are somewhat superior to the people who pull themselves out of that space. This is where I take issue; women, people of color, the oppressed, do not have the resources to stay in that place of eating from dirty dishes in the sink; if we wallow, we die. Only the most privileged person sees that state of selfish unprofessionalism as superior to the person who, through persistence, pulls themselves up out of the shit. When we get there, the privileged literally laugh at us for trying so hard. The gatekeeper then, turns to his lazy brother and compares us and demotes us for having to try hard. Why should someone who is there secure in their position help someone who so obviously wants it? This narrative promotes a logic that supports the people in power, privileges their lazy children and promotes mediocrity. Its at the base of every notion of the abject or the de-skilled in contemporary art. If you are good at something you are trying to hard, you are professional, you are too working class, too clear, to strong, too true. What makes me smile is that clearly this power of entitlement, cannot take the goodness out of professionalism, being good is its own reward. I don’t by the way buy for a second that Andrew Bernardini is unprofessional, he writes too well and is too present in personal interactions to be considered unprofessional. I think he is a try hard like me, like most artists and writers.