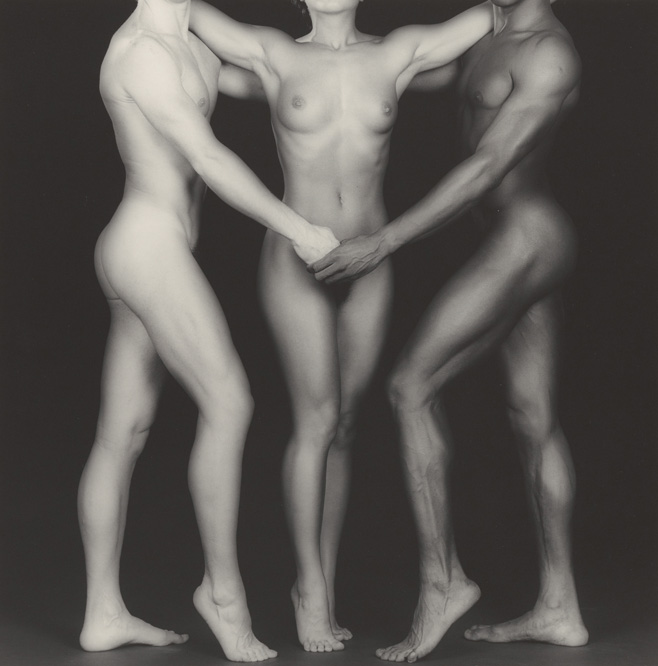

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts can’t send me Robert Mapplethorpe’s most explicit and notorious photographs, despite exhibiting them. It doesn’t have the copyright to do so. Instead, I’m granted access to a slim, gauzy collection of centered, covered nudes, suggestive stamens, and celebrity portraits. I’m grateful for Louise Bourgeois’s picture, in this mix, which pierces the sun-bleached parasol of its press package with her conspiratorial grin, her fur-shirt vaunting while she crooks an arm over a penile sculpture, a forefinger positioned at the head of its tumescent head. Two large balls swell behind her. Sylvia Plath writes in The Bell Jar that the first time she saw male genitals it reminded her of a turkey neck and gizzards. This is that. But it’s the only one of that represented, here, and that’s troubling.

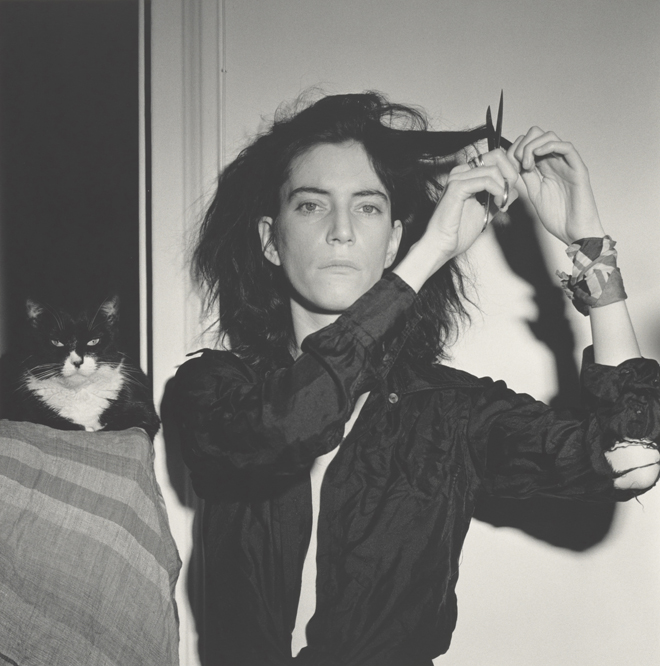

Robert Mapplethorpe doesn’t require illustration, anymore. Most of us can call up, by memory, his most explicit and impactful images. The “culture war” that his scrapped survey, The Perfect Moment, inspired in the summer of 1989 (three months after his death by AIDS, at the age of 42), is well behind us, and yet its second coming looms near. His presence in the life of Patti Smith continues to be underscored through her work (Smith’s Just Kids, an award-winning best-seller in 2010, was a rather chaste account of their creative formation through partnership and friendship). The censorious conservatism that Mapplethorpe initially provoked, and the critical tumult that affirmed the artist’s position on our mantle, is all but shouted about in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s touring exhibition. That we can’t republish his reverent photos of turgid, punctured, stretched, and pulsing sex, alongside his tender framing of blooming orchids, is a dark reminder of a certain ethics of viewing that remains, despite his import – then and now.

***

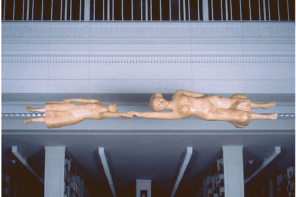

A shabby, aura-infused altar holds the center, and promotes the heart of this exhibition. For reasons unexplained, it’s positioned right-of-center in its alcove, an asymmetry I’ve come to value. It features found or homespun talismans that belonged to Smith. These little amulets are infused with feeling, and accompanied by early examples of Mapplethorpe’s jewelry around the room, evidence of the couple’s magic, materially-delicate beginning (Just Kids helps root this early work as that of an-artist-before-he-knew-he-was-an-artist; the room reads like how a teenager with a morbid, fracturable intelligence might decorate his nightstand). Smith’s songs lap the galleries as part of an audio soundtrack of music and interviews that feels crowding, and overly insistent. Numerous vitrines line the walls, picturing people who existed near, or alongside the artist. The off-kilter altarpiece and fragile ornaments are attenuated by what appears to be the detritus or deconstruction of a zeitgeist; a generation’s parts.

Framing has always been central to Mapplethorpe’s message, and the frame around his legacy matters a great deal as he becomes, increasingly, a figure of both history and portent. What does our presentation of his work tell us about who we are, and what we’re willing to fight for in art today?

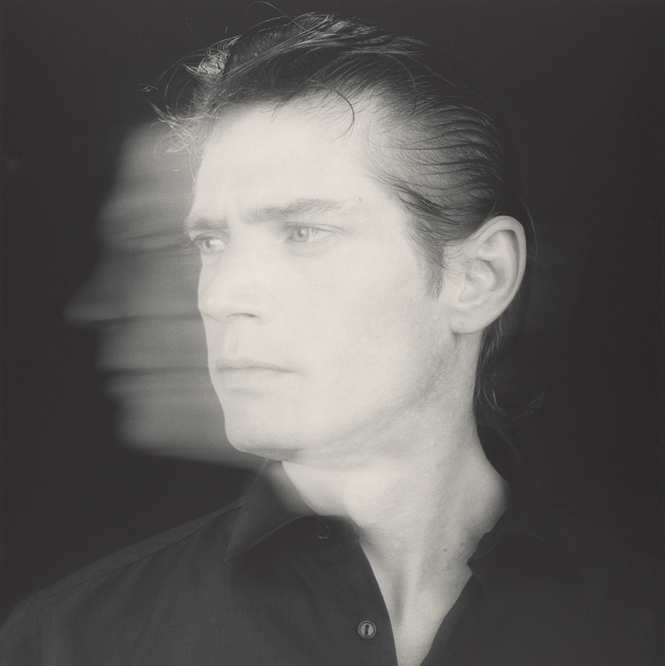

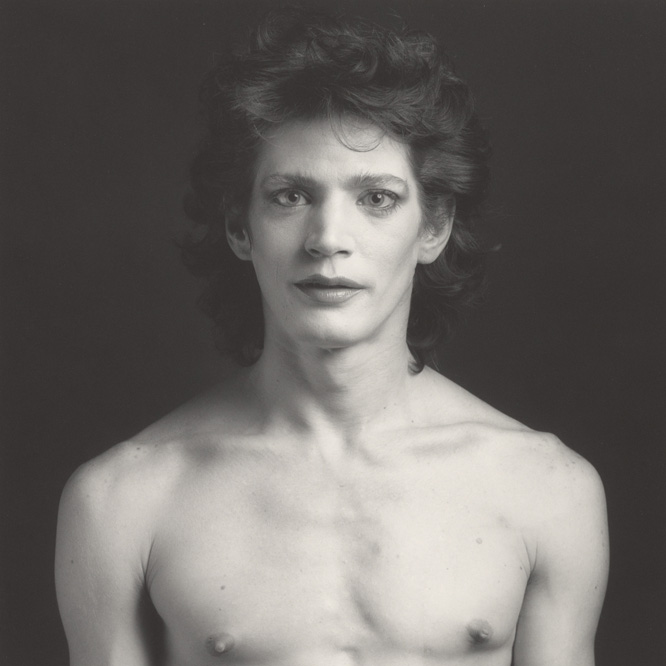

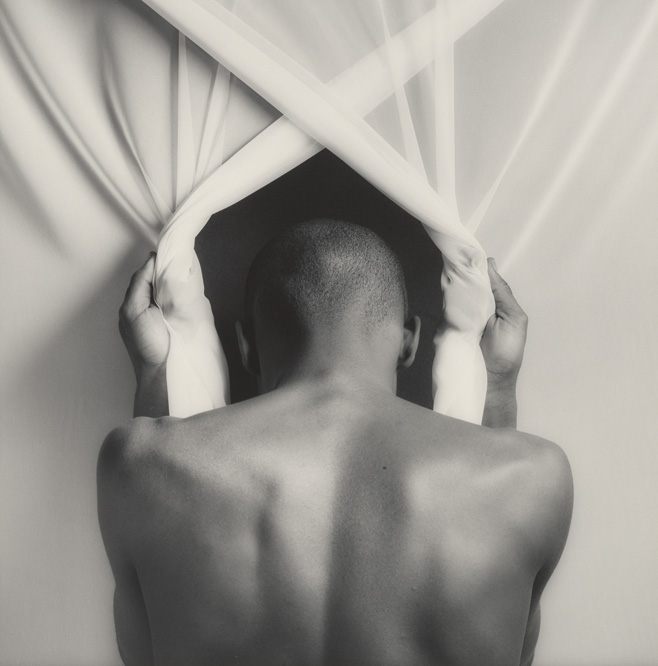

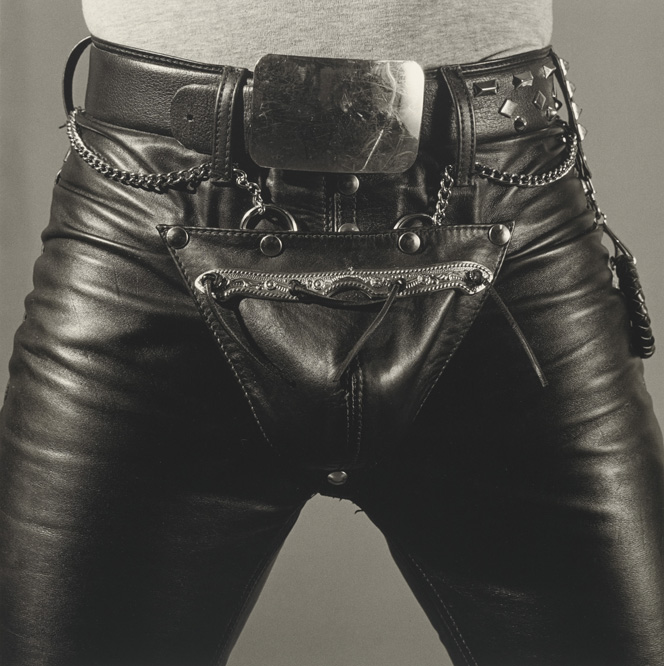

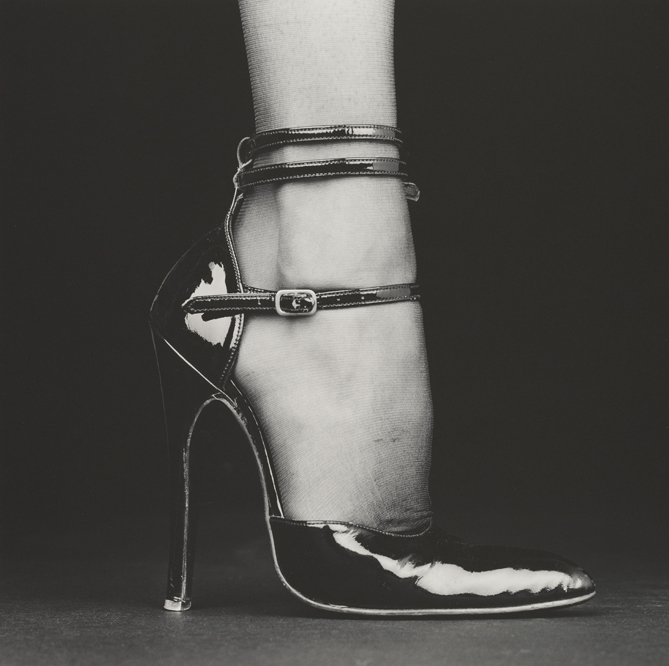

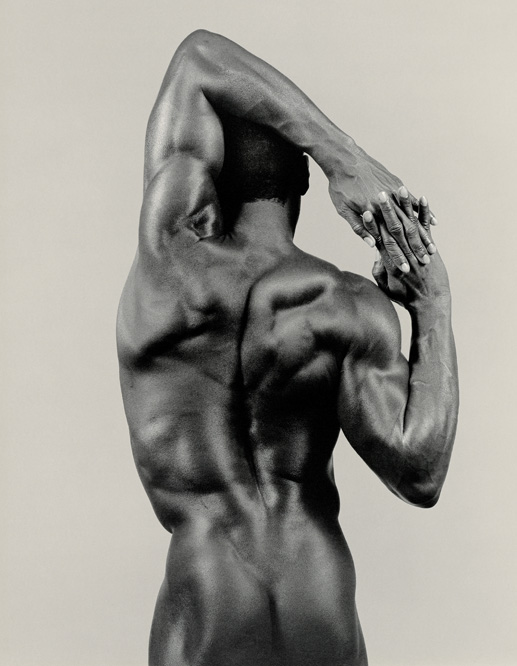

Before a conservative North Carolina Senator blackened the artist’s ascending star, and planted him at the center of a controversy that, even posthumously, would define his career, Mapplethorpe was committed to the poetry and challenge of image construction, and the difficulty of both living and performing oneself authentically. Subjects were secondary: S&M and orchids, they were the same thing.

As Dave Hickey wrote, with his typically charged eloquence, “Robert began in the bosom of the Church and left it to rig out his own language of redemption on the street – a sleek patois of ‘classical’ and ‘kitsch’ that flirted with the low and disarmed the high with charm. These images are too full of art to be ‘about’ it. They may live in the house of art and speak the language of art to anyone who will listen, but almost certainly they are ‘about’ some broader and more vertiginous category of experience to which art belongs – and that we rather wish it didn’t.”

The framing of Mapplethorpe in the touring Focus: Perfection is, then, disappointing for its sectioning of subjects, and the sequestering of like-minded things to exhibition spaces outfitted for their reception. There is the sex room with its neon warning signs, black metallic walls, and gothic, misdeeding energy; the flower rooms, with their pastel paints and clean light; and, perhaps most frustrating of all, the show’s narrative arc, where Mapplethorpe’s start in jewelry (what comes to be seen as “quaint” as the exhibition makes its evolutionary case) goes bookended by a final gallery papered with political cartoons that produce a near-hysterical point about the cultural disruption the artist caused in the months after his death.

“Much has been said about Robert, and more will be added,” says Smith. “Young men will adopt his gait. Young girls will wear white dresses and mourn his curls. He will be condemned and adored. His excesses damned or romanticized. In the end, truth will be found in his work, the corporeal body of the artist. It will not fall away.”

Regrettably, this doesn’t hold true. For Mapplethorpe’s corpus to sing, we need to hear him. But amid a shroud of Smith’s songs and wall texts and peer portraits, album covers, and artefact-lined vitrines, it’s hard to hear the artist at its center, or comprehend what this exhibition meant to say. Planning the retrospective years ago, its organizing institutions (LACMA and the J. Paul Getty Museum in collaboration with The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation and the MMFA; the show travels to Sydney, Australia next) couldn’t have anticipated the heightened relevance – and weight – the example of Mapplethorpe now bears, as we enter a darkening political climate. So what, then, did they want to communicate about the artist’s significance? And why now?

The title can be instructive. Focus: Perfection feels appropriate to Mapplethorpe’s exacting photographic technique, his images’ interplay between light and shadow, and his formidable attention to framing and form (the arching stream of urine from a standing dom into the mouth a kneeling sub is nothing short of Caravaggio for its narrative and compositional instantaneousness and steel). But it’s also a harkening-back to the Corcoran Gallery exhibition that was canceled mere days before its opening, The Perfect Moment, in 1989. In this echoing, Focus is trying to call-up the celebrity of that upset, and position itself as, thirty years on, the artist’s saving grace. It’s a marketing shot across the bow of contemporary art history that could only work if the new show was brave about its subject, and not, as it is, squirrely and diverting.

But the title can also be read as a cleansing of Mapplethorpe’s bigger project: reconciling – both within his culture and himself – the things that warred. His lived experience and perception resulted in a messy intersectionality of religion, sexuality, posturing, exposure, and of course, the attendant formalism of his attempt at resolution. There’s the sense that these competing characters, and the images that resulted, were too much for the LACMA and the MMFA. So, in the face of something overwhelming, they overwhelmed us with themselves.

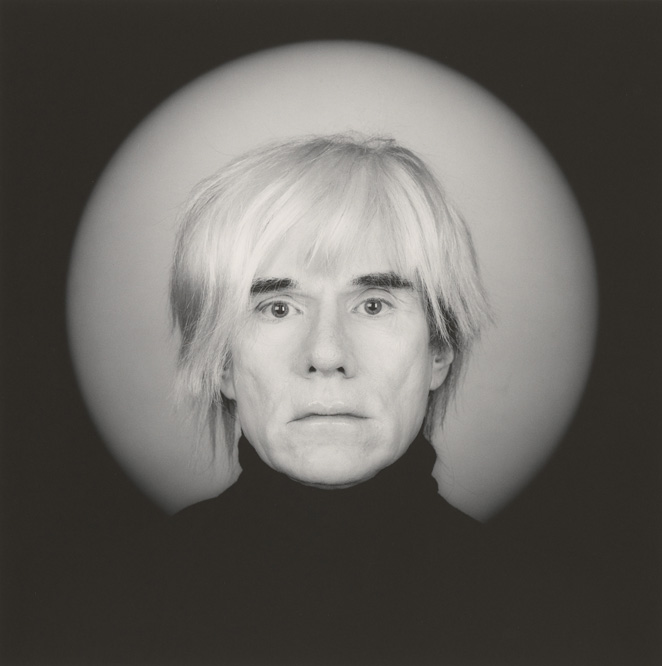

There is, for instance, no shortage of didactic prattle (in Montreal, these wall texts are published in both English and French, creating reams of words, an intimidating glut), but they bear no special insight. We’re given biographical data with Mapplethorpe’s celebrity portraits, though nothing more than Wikipedia could offer – and they focus on their subjects, as if they were the point (“Deborah Harry is an American singer-songwriter”). It’s a reminder that even the museums don’t regard these photographs as art, but documentation – setting Mapplethorpe, and contemporary exhibition-making, back several decades by showcasing a set of images weak enough to renew this distinction. These portraits, however – especially for those of us forging careers in the creative field – serve a pale function, a reminder that every artist needs to make money: that, if we’re lucky and we’re smart, there might exist opportunities for just this within a milieu of a like-minded kin.

As a reprimand to this exhibition, I return to this heart-rending observation from Hickey, that “The axiom that the meaning of a sign is the response to it had, for [Mapplethorpe], a quantitative as well as a qualitative dimension. He wanted them all – all those beholders – and wanting them, he saw the artworld for what it was – another closet.”

While in 2017, our artworld doesn’t need reminding of Mapplethorpe’s value, it appears our institutions do – if only to be checked. Because in a culturally conservative moment, Focus: Perfection is brimming with an art that threatens traditional values – values whose needle, we’ve recently discovered, hasn’t really moved. It’s an art that should be exhibited with bravery and intention, and with a measure of vulnerability, too. Instead, Mapplethorpe is still under cloak of metallic walls – still closeted. His images are presented with caveat, by way of over-explanation, and much diversion. Presented with cowardice. The artist is reduced to his lens, his subjects. The exhibition undoes his body’s whole. As Mapplethorpe himself said, “Art is an accurate statement of the time in which it is made.” Well, so are exhibitions.