There’s no greater risk to our species than the one posed by humankind’s impact on the environment. It’s unnerving how familiar this adage has become, and the myriad coping mechanisms we employ upon its utterance. Odd, then, that one similarity between Documenta 14 in Athens and the 57th Venice Biennale is a lack of direct engagement with the age of the anthropocene. It feels like very little time has passed since contemporary art found in this term a fresh discourse for the politics of human agency, encompassing the environmental, sociological, and temporal reality of our times: the concept of a new geological era formed chiefly by the activity of humankind. Perhaps the three or four years it will take for the Working Group on the Anthropocene to determine which geological formation in particular gives scientific measure to a new epoch is too long for it to stay at the forefront of artworld trends. Nevertheless, the issues raised by the concept are not wholly absent from Venice’s pavilions. The spectre of mass environmental degradation, melting ice caps, and the rise of the digital in every aspect of natural life: these haunt the exhibitions, if somewhat obliquely. And, plodding through a flooded Piazza San Marco late one night after a wilting day of art spectacle and champagne receptions, it’s hard to shake the suggestion of a sinking civilization.

The future of the planet, however, felt quietly sidestepped in Christine Macel’s central exhibition. Rather a more subjective, atomized take on contemporary activism prevailed. This was epitomized by Olafur Eliasson’s woefully misplaced Green Light workshop, which – though no doubt well-intentioned – felt awkward. Taking up one the first rooms of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, migrants and refugees sat around assembling flimsy lights with bemused and curious art cognoscenti. These were in turn available to buy for €250, the proceeds going to legal aid for local refugees. It was pretty soon after this that I decided to step outside the Giardini to find work that eschewed performance in favor of insight scaled to geological epochs, rather than news cycles.

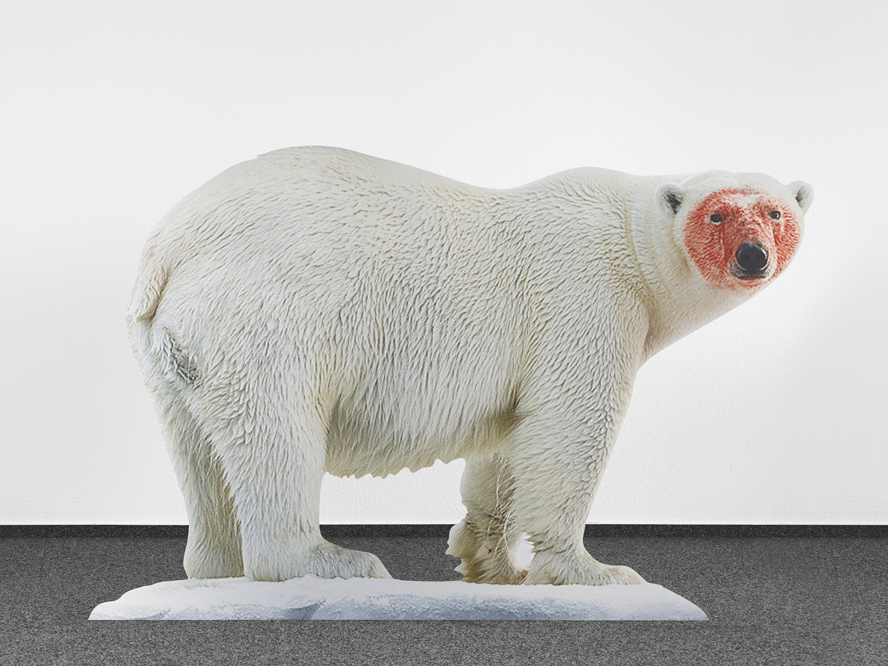

It was in the outlying Estonian Pavilion that Katja Novitskova’s If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes, caught my attention with the words “biotic crisis.” The phrase, like the show as a whole, resonated with urgency: projected onto the wall behind one of her trademark aluminium sculptures: a large, cut-out polar bear. “Biotic,” the show’s pivotal term, is an apt one for Novitskova’s ongoing body of work, exploring how technological advances directly impact upon – and mirror – the systems of the natural world. The curious keyword simultaneously evokes big-pharma, robotics, and animal life; there’s something at once artificial and natural to its ring, much like the exhibition as a whole.

Katja Novitskova, “Approximation (polar bear),” 2017 at the 57th Venice Biennale. Photo: Holger Niehaus.

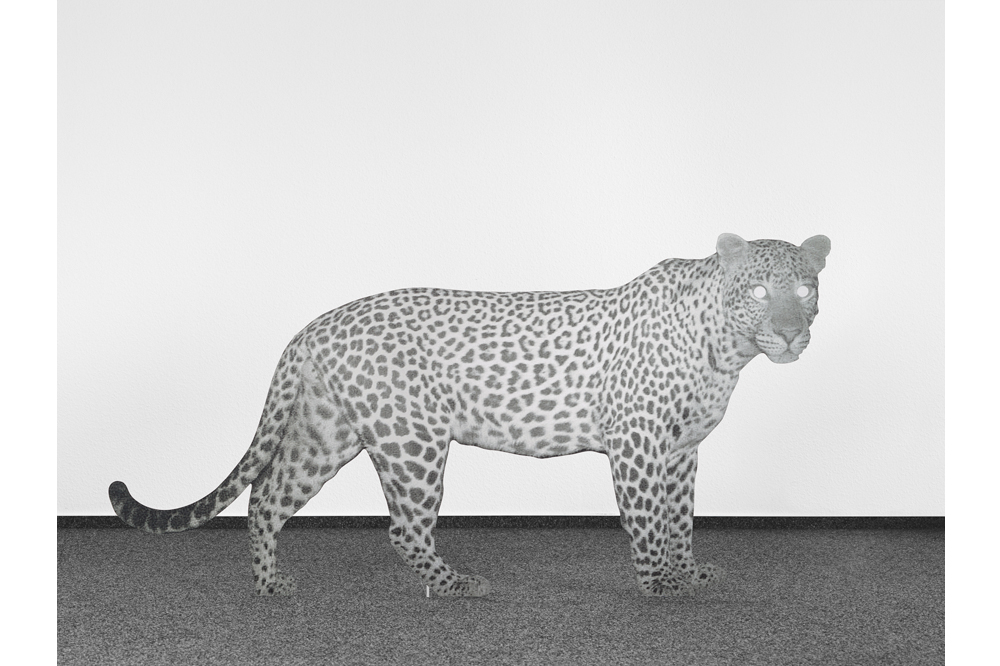

Katja Novitskova, “Approximation (trail camera night vision, lioness eating an elephant carcass),” 2017, at the 57th Venice Biennale. Photo: Holger Niehaus.

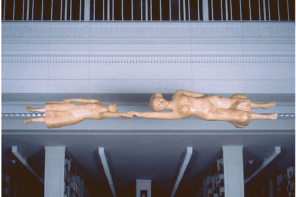

Katja Novitskova, “Mamaroo (patterns)” (detail), 2017, at the 57th Venice Biennale. All images courtesy the artist, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin and Greene Naftali, New York.

Since her 2011 publication Post-Internet Survival Guide, Novitskova has arguably been at the forefront of a generation of artists whose apogee was last year’s politically vapid and uber-contemporary Berlin Biennale. The appropriation of branding and readymade consumer objects renders this immediately recognizable, but the shuttered space of the Estonian pavilion allows Novitskova to display a maturity unusual among her peers. Recalling the world of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner – paid an homage in the show’s title – the rooms feel increasingly sinister in their gloomy futurism. Yet unlike the movie’s rainy and dirty interiors, an uncanny comfort remains in the sheen and gloss of the humming machines, plastic spiders, and copy-and-paste aluminium figures of (often exotic or endangered) animals.

The pavilion feels like a dream of a near-future in which machines have taken over our parental urge to preserve and steward the natural world. Another projected fragment, however, seems to remind us that the oneiric is not the exhibition’s aim. Rather it is our ability to see contemporary reality in its daylight truth: a carefully managed, commodified, automated terra incognita:

the new surface area,

our waking consciousness,

that was colonized

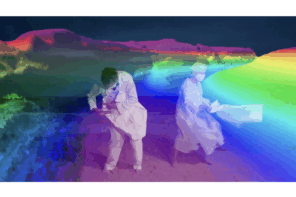

Not far from the Estonian exhibition, the Antarctic Pavilion makes its second appearance at the Biennale, imaginatively realizing a locus par excellence for an art fair of the anthropocene. With Novitskova’s beached whales and polar bears no longer in view, we come upon a monument to the 1st Antarctic Biennale, which took place on a boat in March 2017. Initiated by Alexander Ponomarev and co-curated by Nadim Sammam, the project was (to quote the latter) an “upside-down” biennale based on “supranationality,” whose only audience was the participants themselves. The installation – ultimately a site of documentation for the open-ended “biennale in process” – seemed to pitch and reel, ship-like, under its radical interdisciplinarity. Situating itself as starkly opposed to the standard postures of an international biennale, it might have felt like a parody of the larger Venice fair, if that jab didn’t feel somehow beneath the project’s own global designs.

Such broad ambitions often run up against problems of representation. A clear example of this was the German police impounding Julian Charrière’s intended contribution to the Antarctic Biennale. The seized object was a large air cannon meant to shoot a single coconut taken from a tree on Bikini Atoll. It was designed to evoke a plot within Jules Verne’s The Purchase of the North Pole (1889) to blast the earth off its rotational axis (thereby heating the arctic and opening up new resources for exploitation). Just days before the device was due to ship, nosey passers-by notified the Berlin police of a strange weapon in Charrière’s studio and his intended performance had to be canceled.

An ill-fated, one-man performance for a tiny audience on a boat headed for the antipodes: certainly a far cry from the thick crowds swooning before young models and performers elsewhere in Venice. But then, Charrière’s interest lies more in the complexity of registering geological time than in spectacular au courant political gesturing. This much is equally evident in his Future Fossil Spaces in the Arsenale, which invokes a different kind of temporal play: hexagonal salt sculptures house pockets of lithium, the “white petrol” that will, he imagines, power new technologies such as e-cars.

The institution of the pavilion itself poses a paradoxical venue for contemplating the epistemic problem of the environmental. Whether the frame is national, continental, or conceptual (Macel employs various pavilions to arrange her show, for instance “Pavilion of the Earth” is where Charrière’s work is featured), the question comes back to time: how to appreciate the epochal in the hours or days it takes to move through a biennial; how to move through an exhibition space, and connect that to landscape, landmass, the infinitesimally slow push of a glacier? Perhaps it was this tension that made Geoffrey Farmer’s elaborately dismembered Canadian Pavilion so airily pleasurable, despite its avowedly traumatic core.

Geoffrey Farmer, “A Way Out of the Mirror,” 2017, at the 57th Venice Biennale. Photo courtesy of Megan Williams.

Farmer’s geyser found a claustrophobic counterpoint in Vajiko Chachkhiani’s Georgian Pavilion (he also has a video work in the Future Generation Art Prize). Here, the artist built an irrigation system into the roof of an old forest hut transported from Georgia into the sombre hall of the Arsenale. The house was closed off to the audience: only able to view it from the outside, they looked in through windows at an eternal downpour of misery. Chachkhiani’s is a relatable ruin in a homely apocalypse: one of our most ready-to-hand nightmares, the abandoned home on the outskirt of town, a timeless, organic dilapidation.

The press release describes the Georgian Pavilion’s “slow entropic process of destruction” as Chachkhiani’s ghostly domesticity weaves an emotional tristesse throughout the sad furniture and warping floorboards. It’s a vision of entropy that has its opposite in Novitskova’s electrical devices. Her accelerationist assemblages merge the digital and the human to eerily evoke an already-arrived future. In the current political climate it is not a surprise that such slow processes should be bypassed, but the reality they point toward has it’s own urgency. The contemplation of broader temporality – a poetry of the anthropocene – has left the Giardini behind, and claimed the margins of Venice.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly suggested that the term Anthropocene had not been officially recognized. In 2016, a recommendation was made to the International Geological Congress and it is currently reviewing data to determine the geological evidence to designate 1950 as the start of a new era.

2 Comments