One of the major thoroughfares in the Venetian lagoon, the Bacino di San Marco, is host to a swelling, seasonal parade of cruise ships visiting Europe’s sinking city. Some 60,000 tourists descend on Venice daily during high season, many alighting from each full-to-capacity ship dwarfing the 8 square-kilometer urban center. One could easily imagine an exhibition devoted to these tectonic eyesores, decrying their heinous environmental impact, at any of the official or collateral venues of the 16th Architecture Biennale, this year themed Freespace.

And yet, the crudely-scrawled signage for Cruising Pavilion, presented at Spazio Punch on Giudecca island, just opposite the docks, references something quite different. The name is a perfect decoy to lure a potentially wide-eyed audience to what is actually an erotically-charged invocation of spaces habitually ripe for public, anonymous gay sex.

Your typical club darkroom – prohibitively opaque, dimly red-lit, condoms scattered on a suggestively wet concrete floor – has been convincingly reproduced at Punch. It’s a manufactured space, a deliberate perversion, especially if you take the curators’ position that cruising for sex enacts a “crucial dissidence” in the face of architecture. The project’s curators – Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault, and Charles Teyssou – have put together a strong roster of artists and architects whose work references the topic. The raw exhibition design sprawls across multiple floors: works mounted with wads of caution tape, makeshift separation walls poked through with a Swiss-cheese pattern of glory holes. Cruising is presented here as the “illegitimate child of hygienist morality”: traditionally-sanitized architectural spaces, such as toilets, bathhouses, and parks, transformed into secret meet-up spots for casual sex.

The curators appear resistant to the notion that these sites are only designated for men or homosexuals. Despite their insistence, the artworks present few instances of women and non-male-identified queers actively making use of cruising spots. This likely points to structural reasons why these marginalized groups have eschewed, voluntarily or otherwise, sites of dangerous liaison. In the last decade, cruising has largely taken refuge online – on locative social media like Grindr or, to a certain extent, Tinder – offering a similar casual-sex experience with arguably safer parameters, and opening their accessibility to non-males. These apps are acknowledged by the curators – and in Spanish architect Andrés Jaque’s video contribution Intimate Strangers (2016) – but they lack the risqué appeal of tangible spaces. The curators lament the loss of the “intersectional idealism that was at play in former versions of cruising,” writing that “today, class, race, and gender might be as regulated by the erotic surface of the screen as the architecture of the city.” While it’s not entirely clear how these apps eliminate intersectional approaches, what emerges in this account is a kind of nostalgia for anonymity, lost in contemporary forms of the practice where user profiles and chat functions take away the spatial urgency of the act.

Cruising is fetishized in the show at Punch, if mainly from an aesthetic or architectural perspective. This seems flippant, especially for those actively seeking safer spaces for queer sex and expression (a red flag to anyone aware of Toronto’s recent serial abductions and murders of gay men, for example). Admittedly, the exhibition is designed as a provocation; one meant to specifically target the Biennale’s characteristically innocuous theme. This year’s Biennale curators, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects, have optimistically defined “Freespace” as a “generosity of spirit and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture’s agenda.” Cruising Pavilion, by contrast, posits that the supposedly “free” spaces of architecture are decidedly heteronormative by design, and that cruising is, and has historically been, an essential counterbalance. In a reworked version of the Biennale manifesto published on their website, the pavilion curators have replaced each instance of the word “Freespace” with the word “Cruising,” to campy effect: “CRUISING FREESPACE provides the opportunity to emphasise nature’s free gifts of light – sunlight and moonlight, air […]” says one. Or “CRUISING FREESPACE focuses on architecture’s ability to provide free and additional spatial gifts to those who use it and on its ability to address the unspoken wishes of strangers.” The almost seamless substitution highlights both the theme’s generic nature, and the versatility of cruising, as it impartially occupies secluded natural and manmade venues.

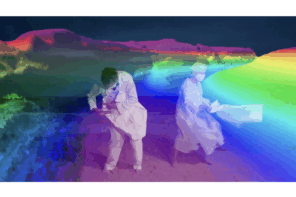

The pavilion opened with a party that, rumour has it, actually turned Punch into a cruising spot, if only for the night: the invitation even promised poppers to its guests. The opening weekend also included a tour of the historic “Garden of Eden,” a widely documented cruising spot on Giudecca, used actively from the end of the Belle Époque to World War II and now closed to the public. In the exhibition itself, the practice is shown to be ubiquitous, resonating with architects in ways they likely didn’t anticipate. Reputed architecture office Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s 2002 projects Blur and Blush make an unlikely appearance in this dingy setting. The Blur building in Switzerland was realized for the Swiss Expo in 2002, creating an “architecture of atmosphere” by using fog from water pumped out of Lake Neuchatel. The effect was a kind of whiteout that set the stage for the performance piece Blush (2002). This work took the form of a wearable locative app: a raincoat that produced bodily sensations as potential “matches” (determined by a nonsensical questionnaire) approached one another in the hazy space. Its inclusion in Cruising Pavilion, opposite a small wall-mounted cool mist machine, playfully repositions this work within a history of gay sex and architecture’s hidden spaces.

We can trace the history of cruising alongside that of specific architectural sites. British artist Prem Sahib shows photos from his series Chariots Shoreditch (2016), a collaboration with Mark Blower. The work examined the design of Chariots, London’s largest gay sauna between 1997 and 2016, as it was closing to make way for a luxury hotel development. The closure, alongside Chariots Waterloo, marked the end of an era for London cruising. Nearby, a historical account of one of Europe’s best-known cruising spots – Platzspitz in Zurich – captures the aura of another physical space that served for several decades as a reliable gay meet-up spot, before it became a local haven for drug use and was cleaned up by the city in the mid-1990s. These accounts trace the transition – or even gradual death – of the practice.

Other works underscored the way that desire becomes embedded in physical spaces. Berlin-based, Venetian artist Monica Bonvicini’s text-based work Warning! Failure is to Follow (2015) also features at Punch, describing an eroticized construction site whose main protagonist is a power tool. As befits the subject matter, the piece begins: “After all, electric shocks, fire and/or serious injury can produce some excitement, / Dirty and dark areas invite accidents.” Bonvicini’s work, while not obviously referencing cruising, tackles questions of power and phallocentricity from the perspective of the S/M community, and how these get embodied spatially, whether through smoothly-designed architecture or crude construction. The invocation of the titillating nature of “dark and dirty areas” brings us back to the space of possibility opened up by the exhibition itself.

Attending to a rich history of this sexual practice, Cruising Pavilion is a truly original answer to yet another banal Biennale. As with any attempt to archive sexuality in an artworld setting, the exhibition definitely pays homage to cruising, leaving it tantalizingly passé and perhaps ripe for rejuvenation, though virtually unquestioned in its assumptions. Nevertheless, the exhibition offers a rare glimpse into what the curators quite convincingly insist is architecture’s inevitable, underlying relationship to queer eroticism.