On May 28, 2017, MASS MoCA inaugurated its new Building 6, doubling its existing gallery space and turning the 16-acre complex of abandoned, 19th-century factory buildings into the largest contemporary art museum in the United States. But size is not its only salient feature: the museum is an experiment in new forms of programming based on partnerships with artists, foundations, and other institutions meant to make it a heterogeneous and welcoming place.

The question, of course, is “welcoming to whom”? At the Sunday morning celebration of its opening, a friend and I played a joking game of counting all the people of color there – something I have long done in these parts, feeling, as I do, like a fish out of water in the overwhelmingly white cultural spaces of New England. (We counted five, among several hundred.) But any humor I found in the situation dissipated as I realized what I was being asked to celebrate: a building devoted almost entirely to the work of white artists. How, in 2017, could this happen? Paradoxically, it seems that the very strategies the museum is pursuing to open up its space to multiple voices are themselves responsible for ensuring that the only voices heard are the usual suspects. As is often the case with American racism, this exclusion was slow, systemic, and paved with good intentions.

There’s always been a lot riding on MASS MoCA’s success. The museum came into existence in the wake of the shutdown of its region’s largest employer, which had occupied the campus for many years. Its original promoter, former Guggenheim head Thomas Krens, and its longtime director, Joe Thompson (a Krens protégé) promised it would be an engine of economic development, and hopes were high that it would radically change the fortunes of this hardscrabble, working-class town in the Berkshires and the surrounding area.

Certainly MASS MoCA has had a positive impact on the town of North Adams in the thirty years since the painful process of deindustrialization began. The unemployment rate has dropped significantly, and its 165,000 annual visitors, alongside the businesses housed in MASS MoCA, add a reported $22 million to the region. The museum credits itself with the creation of 383 jobs. That said, MASS MoCA itself only employs about 65 full-timers, a minuscule number for an institution with 250,000 square feet of gallery space to program. It has an insignificant endowment and a tiny operating budget for an institution its size.

In the face of these economic realities, Thompson was forced to create innovative models for programming: because the institution can’t afford a permanent collection, it relies on temporary exhibitions and long-term loans; because it can’t afford to take on more curatorial staff, it makes room for artists, foundations, and estates to fill its spaces.

The approach began with a partnership with the Yale Art Gallery, resulting in a 25-year loan of 105 Sol LeWitt wall drawings, and continued with a 2013 deal with the Hall Art Foundation to turn over an entire building to the work of Anselm Kiefer. Building 6 continues these sorts of partnerships in the form of a 25-year long installation that amounts to a 35,000 square foot permanent museum exhibition of the light works of James Turrell, and two 15-year long space commitments to the artists Jenny Holzer and Laurie Anderson, both of whom plan to use the space as a site for creative experimentation and display.

Thompson spins his solutions to economic obstacles as an experiment in curatorial democracy: “Ours is an unusual museological model – most museums don’t turn over curatorial authority, and precious space, to others – but we welcome the incremental, organic layering of outside, independent voices, and multiple points of view,” he writes in a recent op-ed in the local paper, The Berkshire Eagle. “In many ways, MASS MoCA feels a lot more like a turntable than a white box of perfectly illuminated space or maybe more like two turntables and a microphone.” (The last phrase is a clever citation of a song by Beck, an artist who has both contributed work to Tim Hawkinson’s grand installation Überorgan, which filled the massive, football field-sized Building 5 in 2000-1, and performed at MASS MoCA in 2014 before an audience of 6,500 people, including myself.)

There’s an overt utopianism in the language. Here’s a museum that is willing to give artists authority over their own work, make space for multiple points of view, to open doors wide rather than act as a cultural gatekeeper – with a DJ rather than a museum director at its head, no less! Certainly, many art critics who have visited the complex point to the open atmosphere and populist approach.

Despite the laudable openness, though, Building 6 shows the limitations of its unusual model when it comes to achieving real diversity. While the museum’s handful of curators have, of late, made impressive strides in expanding the rotating exhibition program to include artists of color and indigenous artists (including the current year-long installation of Nick Cave’s spectacular Until, housed in Building 5), the monumental spaces of the new facility are, at least for now, devoted to long-term exhibitions of works by almost exclusively white artists.

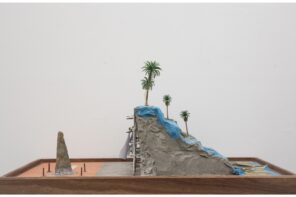

Rounding out the work of Turrell, Anderson, and Holzer are medium-term shows (on view “at least through 2018,” per the museum’s website). These include the homemade, “music for the people” instruments of Gunnar Schonbeck; a confection of lightbulbs by Spencer Finch; massive photographs of Building 6 pre-renovation (made from a shipping container transformed into a large-format camera) by artists Lauren Bon, Richard Nielsen, and Tristan Duke of the Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio; and a technically-ambitious but somewhat boring 9 x 16-foot watercolor of the empty spaces of Building 6 by Barbara Ernst Prey. Also on view in the building are works by Louise Bourgeois, Sarah Crowner, Sol LeWitt, Joe Wardwell, and Janice Kerbel. (One of the best works in the complex, Lorem Ipsum by North Adams-based artist Mary Lum, occupies a passageway just outside the building itself.) In another partnership, the Rauschenberg Foundation, which lacks exhibition space of its own, has been given square footage in Building 6 to install works by Robert Rauschenberg as well as to install rotating exhibitions of artists who have completed residencies at the Rauschenberg Foundation.

While on the surface a canny solution to a perennial lack of funds, MASS MoCA’s programming strategy of prioritizing long-term installations devoted to a few artists hand-picked by the director means that the opportunities for engaging a broad range of voices is limited. A great deal of space is devoted to a small number of voices, even if those voices are undiminished by curatorial oversight. That their choice was determined by Thompson alone was underlined by Jodi Joseph, the institution’s director of communications, who emphatically explained to me that the six artists the museum hopes to have on long-term display (Turrell, Anderson, Holzer, Schonbeck, Bourgeois, and Rauscheberg) were “always part of Joe’s vision, he hand-picked them and has worked to make it happen.” Despite the democratic overtones, MASS MoCA is not a jukebox, where multiple people determine the playlist: it really is a single DJ selecting the tune.

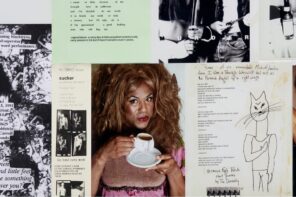

And if that DJ only likes one kind of music? Well, it’s not for nothing that much of the music programming at MASS MoCA – an aspect of its programming that carries equal weight to its art activities, in terms of budget and bandwidth – tends towards white-bread “Dad Rock.” Consider this: of 125,000 square feet of exhibition space in Building 6, a mere half of a modestly-sized gallery was turned over to a black artist. And the inclusion of this artist – Atlanta-based Lonnie Holley – is under the auspices of the Rauschenberg Foundation, where he completed a residency. (Dawn DeDeaux, another Rauschenberg Foundation artist, shares gallery space with Holley; notably this is one of the few rooms in Building 6 that listed a MASS MoCA staffer, Denise Markonish, as curator).

Holley’s sculptures, composed of discarded materials assembled into uncanny, even menacing combines – an obsolete voting booth with pistols aimed at the voter’s head, a pile of broken musical instruments, their wooden shards as fragile as bodies – seemed to me the most interesting on display. Their presentation was manifestly not motivated by the same kind of retrospective (or even navel-gazing) urge as the installations of Turrell, Anderson, and Holzer. I wonder if anyone noticed the irony that Holley turned to exhibiting in art spaces only after a long-term “installation” he made in the backyard of his house in Birmingham, Alabama, was destroyed (house and all) to make way for the construction of another “engine of economic development” – in this case, the construction of a new airport.

But it’s not that black artists and black art weren’t visible at the opening: there was a parade featuring dancers in Nick Cave’s Sound Suits, choreographed by Sandra Burton. Holley and DeDeaux gave a gallery talk, and the singer Helga Davis performed in the galleries as members milled around. And, to the delight of the overwhelmingly white crowd, the Brooklyn United Marching Band, an African American children’s group, gave an excellent, rollicking performance of Beyoncé hits. They were bussed in for the event, and bussed out after; as far as I’ve been able to ascertain, there was no particular logic to their inclusion in the program.

As I watched the museum-goers eagerly snap pictures of these talented young children, seemingly oblivious to the deeply problematic racial dynamic on display, my stomach sank and my bile rose. It wasn’t that blackness was erased from the opening festivities, rather it was made to serve its usual function in a liberal institution: to act as a cover for the museum’s almost exclusive investment in whiteness. Blackness was present as spectacle, as performance, as entertainment – but wasn’t afforded the primary thing MASS MoCA has to offer: namely, real estate. Strip away these fleeting performances and what remains is a monument to white art, a point that was painfully apparent when I revisited the building after the celebrations were over.

I don’t think this was deliberate, in the way that most racism in the United States is not deliberate. It was the function of a set of decisions that seem at first logical (hand-pick artists, estates, and foundations to create long-term installations of art in exchange for curatorial control of the space), but inevitably have uneven consequences (if your choice of artists is exclusively white, you are locked into an exhibition program that seems to venerate whiteness). Questions abound: if this is the outcome of the strategy, how could it possibly be worth pursuing? If the only way we can imagine making museums solvent also furthers their role as bastions of white supremacy, what does that say about our imaginations? What does it say about the continued relevance of our museums? And how, in the end, does such a strategy serve a community like North Adams, whose population is not, in fact, as white as this event would suggest? It seems to me that MASS MoCA needs to do some soul-searching to find some answers – preferably with some people of color in the room.

If the author had set foot in Buildings 4 and 5, she perhaps would have noticed the exhibitions “Steffani Jemison: Plant You Now Dig You Later,” and group shows “In the Abstract” and “The Half-Life of Love,” all on view closest to the museum’s entrance, and leading into Nick Cave’s spectacular, explosive, beautiful “Until.” In the aforementioned exhibitions, young black artists are given plenty of real estate to show works that are formally experimental, evocative and emotive, without ever being consigned and signposted as “black art” – perhaps this is why the author missed them in her hurry to pay lip service to wokeness by branding Jim Turrell a white supremacist, and MM by association.

Haven’t we heard enough about him, about Rauschenberg, about Jenny Holzer? If the author was truly interested in representing artists of color, she’d use her platform to write critically about Steffani Jemison, Rodney McMillian, Eric N. Mack, Tomashi Jackson, Kambui Olujimi, Jordan Casteel, etc etc. The criticism of Building 6 is valid, but as it stands, the title and the text bely strategic omission on D’Souza’s part to dramatize her point. Without discussing the museum in its entirety, but purporting to do so with a click-baity woke-olympics title, D’Souza enacts the same erasure she accuses MM of committing.

I go to Mass MoCA once a month at least, and have seen the works you mention (and referred to the great work of the curators of the rotating exhibitions in my piece). Howvwe, temporary exhibitions and long term installations do not represent the same thing when it comes to museums. An analogy would be museums who show lots of black artists temporarily but never add them to the permanent collection. The museum counts on viewers not to notice the difference, but if one wants to combat institutional racism, these are details that matter.

I assumed the marching band was there to celebrate the Southern artists exhibition — Dawn DeDeaux of New Orleans & Lonnie Holley of Birmingham— two great living artists that haven’t received much institutional attention in their long careers and the New Orleanians among us were happy to feel at home with the band there albeit we were the only ones dancing…

The band was also in conversation and performing with the live Nick Cave piece throughout the entire day, not just bussed in and out for the “Beyonce” hits, which wasn’t their only claim to fame. I agree with you on most of your points here and as I saw your headline I knew a complaint would be made about the band; but I think there was more to it than the negative spectacle you described.

According to the Mass MOCA press office, none of these things were the case. The band was there because it was considered art by the programmer. Period.

It was art; that’s not at all my point. So an interpretation of it otherwise is wrong. Period?

This critique is a gross misinterpretation of Mass MoCA in every way. As another commenter has noted, Mass MoCA has done a wonderful job of representing many many cultures, without labeling them and categorizing them as if they needed to check off the cultural boxes, but rather they are “artists.” Period. I reject the analogy ‘exhibiting artists of color but never adding to their collection’ because as already explained, there is no such comparison; this museum is an innovative and very different type of institution. I was at MoCA on July 6th, and came away impressed at the richness of the exhibitions, colturally, intellectually, and visually. Obviously this writer simply wanted an artist of color to be one of the three artists in new building 6. There are only three… and they are world renowned and worthy of the space. With so many artists of color in other equally important areas of the museum with rich and meaningful work, this is a false and inflammatory claim. Smells like an ax to grind, I am sorry that the opening was the target. And the author reduced the performance artists at the opening to a stereotype with the characterization offered.

This is an unbelievable smear on this fine museum, as other commenters have already eloquently pointed out. It sounds as though the author needed to write a piece on the museum and, seeking clicks, found a subject. I congratulate her on this front, because I read the entire thing and am now commenting.

I’m sorry so many happy white people came to an event that you also attended and enjoyed it? I’m sorry that North Adams is literally 93% white and probably, mostly local people showed up for this event? My god.