To read White Girls, Hilton Als’s 2013 collection of upending essays, is to feel calcified assumptions about sexual and racial identification dissolve. A chain of incisive reflections on cult figures in art, fashion, and music, the book caused psychological tremors even in the self-assuredly enlightened. Therein, Als implicates his desire in a deceptively labyrinthine memoir – as he does in this exhibition, One Man Show: Holly, Candy, Bobbie and the Rest, at The Artist’s Institute, a project at Hunter College. Here he has conjured like a cast of ghosts an enigmatic milieu that nurtured his want for more complex forms of identity and intimacy. The party people of New York’s drag and disco scene in the 1970s appear in Als’s photographs, concatenating experimental films, and slight sculptural gestures, all bathed in cheap colored lights. Music – from original disco tracks to a knee buckling J Dilla instrumental – drifts in and out, emphasizing the simultaneity of disappearance and foreverness, which is as much the subject of One Man Show as the people pictured within it.

For many, Als is first a writer and only now an artist. But throughout his career in writing criticism for The New Yorker and Village Voice, he made art “as a relief from language.” This want to escape linguistic strictures was discernible in White Girls. There are passages where, tracing complexes of affinity and attraction, Als drops structure altogether. Sentences crumble into colloquial air, before being pulled into cohesion by the mesmerizing specificity of his portraits. Similarly, this show often threatens to disappear into a wistful haze. In an accompanying essay, Als writes that his art “has always been other people” and the option that they give us “to ask: who will I be now?” This thought is beguilingly optimistic, and clearly influences Als’s wish that his art be accepted as contiguous with – not secondary to – his writing.

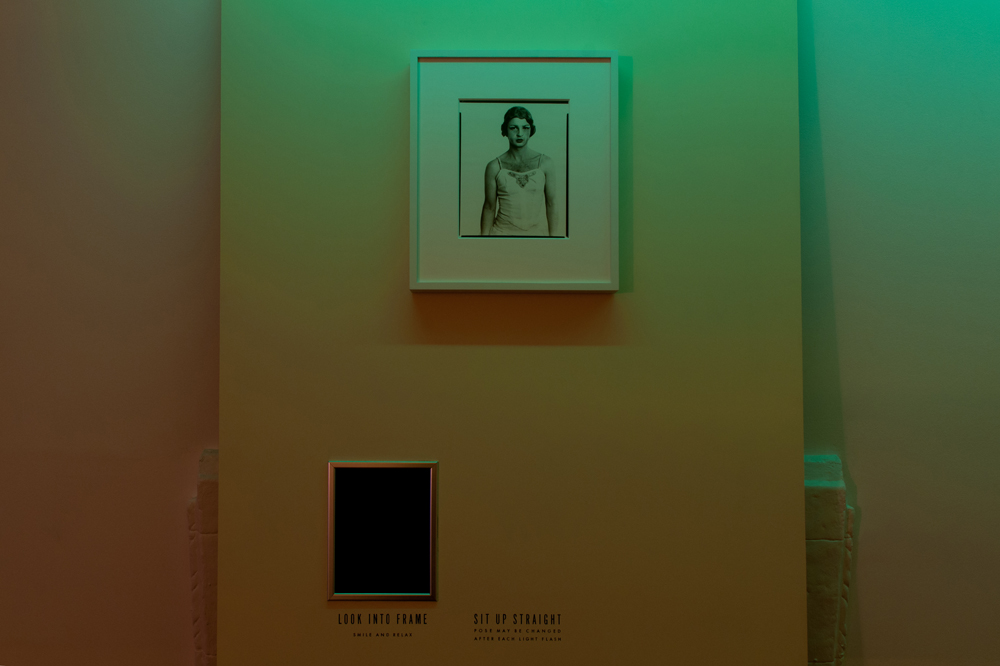

In a room called the library – referring to the gallery’s residential past-life – Als has leaned an upturned sheet of MDF over a disused fireplace. This board holds a framed photograph by Richard Avedon – John Martin of Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, New York, March 15, 1975 – and a metallic picture frame circumscribing a black void. Text instructs viewers to “look into the frame and relax,” and to “sit up straight.” In Avedon’s photo Martin is a thirty-something white man. Shown from the waist up, he is wearing heavy makeup and extravagantly swooping eyelashes. A hairnet compresses his voluminous wig and a snug, strappy dress brackets his well-built shoulders and wispy chest hair. Titled Smile and Relax (for Brent Sikkema and Kenneth E. Silver) (2016), and alluding to a photo booth in order to model circuits of projection and fantasy, this piece strikes a flat note.

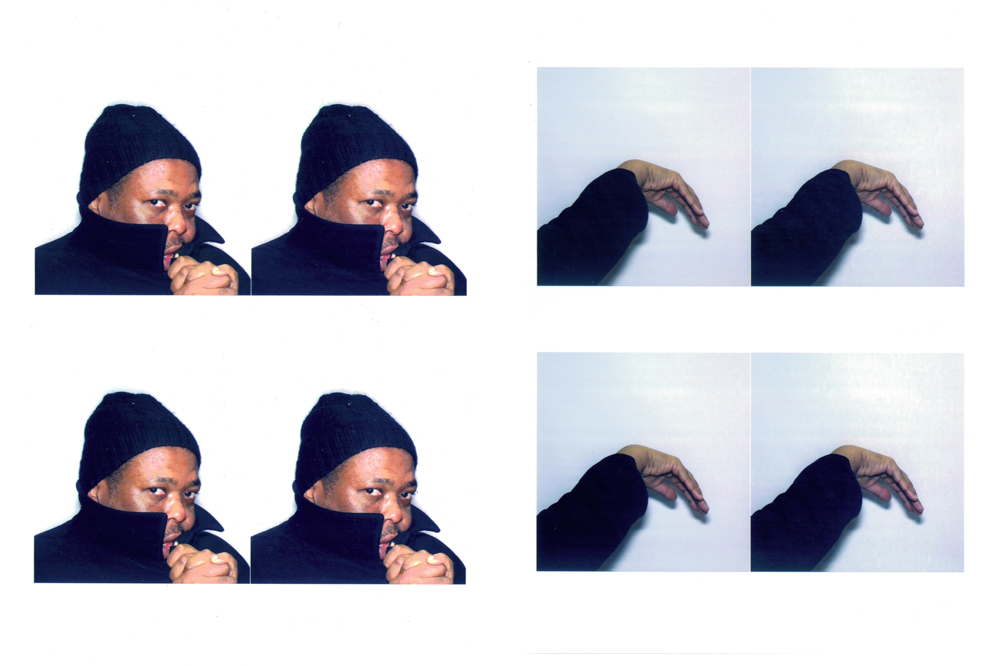

The more Als disregards conceptual concision, the more interesting the show becomes. A queer icon and black man, he made the fraught and compelling decision to dedicate an entire book to white girls. That title was really a cypher, though, splitting facile assumptions about whom a person should identify with, from the nebulous reality of affinity. He traces the deeply incongruous identity, for example, of André Leon Talley, the American editor of Vogue, who as a black youth living in Paris, absorbed that culture into their comportment while being verbally accosted by its racism; as well as Eminem, a white rapper whose mixed up racial identity Als thoughtfully elucidates in the context of urban American poverty. In this show, Als’s insouciance towards neatly compartmentalized identities is signaled most clearly in Portrait of Myself, But As Which One? (2016). Here, on two white shelves, Als has placed books featuring his own writing near two unframed self-portraits, each showing one image four times over. In the first of these, he glances at the camera over an upturned collar, recalling Orson Welles in F is For Fake (1973). In the second, his hand is held aloft, his wrist torqued, in an essentializing gesture. Underneath these shelves, in Diana Davies’s photograph Unknown Attendee at Gay Liberation Front Meeting (1968-75), a youthful black man stares out through deep, soft eyes, hunched slightly, hands folded casually over his thighs, and a scarf tied around his head. An aluminum construction lamp saturates this alter to the un-unified self, in red light.

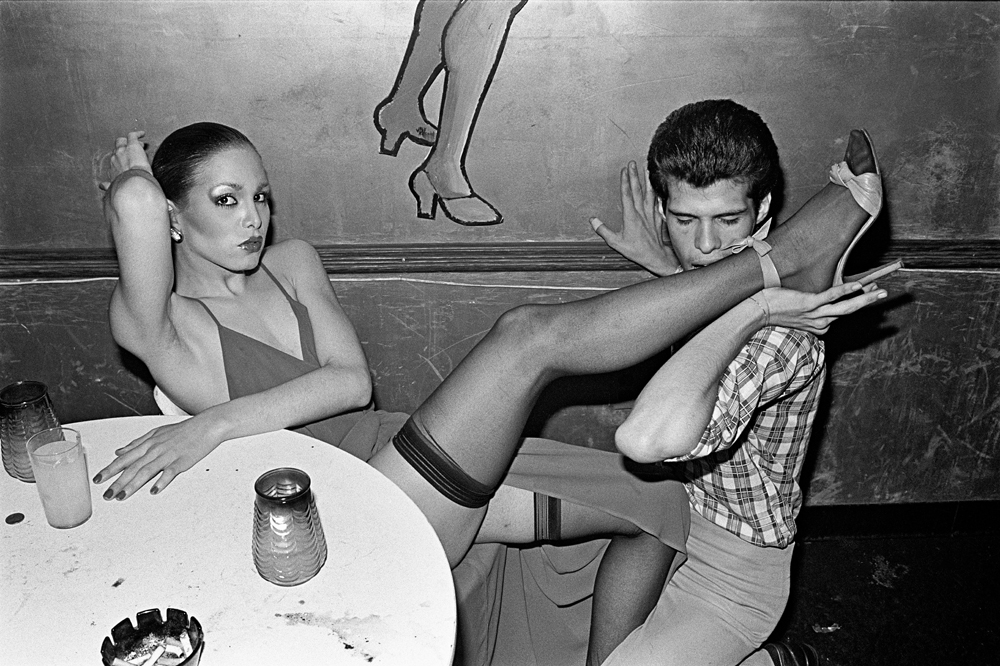

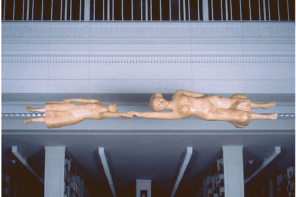

Having been walled over a few steps up, a curving staircase displays traces of the 1979 New York disco scene, in Dirt Nap/Disco Nap (2016). A silver-stanchioned rope fronts the false wall on which Als has reproduced a poster for GG’s Barnum Room – a club in Manhattan, he writes, “frequented by trans people and their admirers” and “one of the only places in the city where men and women and everyone in between could be safe when they threw up their hands in something resembling freedom.” A rich ensemble of typefaces offers “A CIRCLE OF LAVISH ENTERTAINMENT!” and “DISCO BATS!” (referencing the sculpted dancers who swung from trapezes high above the club floor). Overlaying this text, projected slides show the club in action – two bats, for example, lying in a mesh safety net that rhyme nicely with a fishnet leg in a photo around the corner. It’s impressive to observe Als’s economy of means, with an effortless transposition of text and projection, here forming the quiet apparition of a once-vibrant place.

The resemblances between this exhibition and the virtuosic eccentricity of F is for Fake circle around that small photo of Als, and emanate through the show. In contrast to Welles, Als has less the prodigious ambition of an auteur than the care of an affectionate host – even as that care discloses a need to be surrounded by people, to be made safe. Als isn’t fracturing concrete reality, but offering tribute to people whose identities never hardened into any readymade option. In this way, the exhibition is deeply empathic – not only to its subjects but the viewers whose worlds are now more dazzling for encountering them. This empathy is deftly tuned with Als’s decidedly non-invasive way with materials: the simple overhead projector, cheap construction lamps, MDF board.

There is a casual affectation to the way in which Als has hung a bed sheet in the gallery’s study, to serve as a makeshift projector screen for films by Darryl Turner and Werner Schroeter. And this attitude was echoed in the free association of Turner’s film D’Arc-Ness (1999–2016), which cross nonsensical images (a foot, a bull, a young girl side-eyeing the camera) with ones closer to the show’s theme (so many fresh faced young people, including a woman dressed as a nun and pantomiming gravitas) into an aggressively-cut montage. Two wall-scale pieces of cellophane hanging in the rear-most sunroom echo this bed sheet’s chiffon character, but with industrial undertones. Respectively titled Silver Candy and Candy (both 2016), each has been embellished with silkscreen ink, one almost uniformly covered and the other with just a few slight stripes along the edges, but both flaking and peeling. Ironically, this was the exhibition’s most narratively opaque work, hinting at a more metaphysical story about surfaces and transparency, and the strangeness of expecting one thing to hold onto another everlasting.

Many other photographs picture “the rest” whom the title alludes to. A photo by Diane Arbus of drag performer Stormé DeLarverie – Stormé Standing in the park with a cigarette, NYC (1961) – is singularly arresting. Here, our protagonist is wearing a tweed suit. His hair is cropped short and his stare, unflinchingly encountering the camera and toned by his lightly pursed lips and the way his strong cheekbones have been muted by makeup, hovers between poise and worry. As one component of Als’s installation titled Storme, Bobbie, and the Rest (2016), this image sits in the beam of an overhead projection showing two people standing in a parking lot. The latter two play faded shadows to DeLarverie. But that’s to be expected. Who could compete for our attention with the combination of Diane Arbus and an iconic drag king?

This exhibition cycles through surface effect and touching individuality. It is easy, in our own imaginations, to call up clichéd images of drag queens and disco dancers. But this doesn’t stop a photo of performer Ethyl Eichelberger – with barely-parted lips and a lazy sideways glance through drowsy eyelashes, lifting his thin arms to fix a mountain of blonde hair – from entering us, so that we can see the person, rather than the stereotype. Images of ankles being kissed while cigarettes are ashed emanate un-weighted promiscuity, while others, like Als’s photo Mx Justin Vivian Bond as Mx Justin Vivian Bond (2009), slow cross-cultural, cross-gender, cross-taboo trajectories. The photo pictures Bond, an artist and drag performer, facing the camera, arms folded, wearing earrings and a red blouse. Bond doesn’t appear to be performing. And so the photo corresponds more closely to something that many people might, forgetting the word’s hidden connotations, call normalcy. This image is no less a fiction than any other in the show, and contributes substantially to the exhibition’s depth.

The exigencies of life compel us to simplify people and relationships. In One Man Show: Candy, Bobbie, and the Rest Als shows us a world un-beholden to such debilitating expediences. His way of approaching this history is not documentary, but re-animation by way of an ethereal, ad-hoc nightclub. Sometimes verging on flashy nonchalance, Als’s light touch emphasizes the tenderness necessary to make this incantation work, over the imposition of artistic motives, and critical incision. This is an enlivening contribution; one well conducted by a visual artist who, like an incognito performer, is only one when he decides to be. It’s not as if the world he’s picturing didn’t have problems. It must have. So does this exhibition, which is sometimes too airy, and too expected, even as David Bowie – reverently eulogized by Als in The New Yorker – croons in the background: “So you think I’m dressed to impress you… I think I may caress you… I walk a fine line…” Such lines often dissolve.