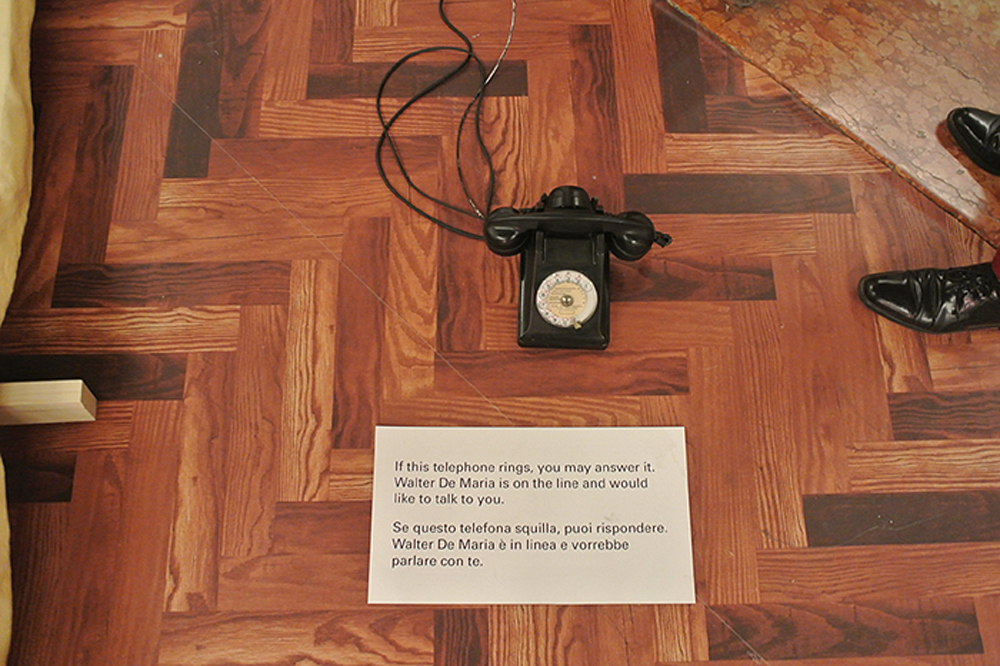

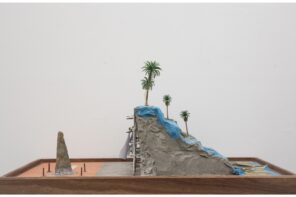

The image above is an installation shot from When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013. It was a recreation of Harald Szeeman’s famous exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, shown in a Venetian Palace occupied by the Fondazione Prada. The 2013 exhibition’s curator, Germano Celant (who worked on it “in dialogue with” artist Thomas Demand and star architect Rem Koolhaas), conceived of the original 1969 presentation as a “readymade,” which he then “restaged” in Venice. The 2013 show presented the same artworks as Szeeman’s original and the arrangement winked at the Bern one, with lines on the floor demarcating the organization of the space at the Kunsthalle Bern.

The subtitle of Szeeman’s show was “Works-Concepts-Processes-Situations-Information.” Attitudes was revolutionary because it reflected a then-current mode of production (which included what we now refer to as Land Art, Conceptual Art, Arte Povera, and other proximate movements) that was immaterial. The word information in the exhibition’s title is especially crucial here, since Szeemann’s interest was not necessarily in showing work, per se: it was in showing working processes. Fast forward to 2013, where a dematerialized attitude takes the form of objects once more.

Attitudes was far from the first exhibition to have been restaged. There was Other Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2014, the title’s “other” connoting that the show reexamined the historical Primary Structures: Young American and British Sculptors from 1966 at the same museum. And in 2012, the Brooklyn Museum mounted Materializing Six Years: Lucy Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art. Focusing on Lippard’s influential book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object 1966–1972, the show included artworks from the time, alongside ephemera from exhibitions of that period, catalogues, artists’ books, and so on. While Lippard centered on the political contexts and possibilities of the art she was analyzing, the Brooklyn Museum exhibition cordoned off the sections dealing with “politics” and “feminism,” leaving the main stage to the art objects and vitrines of collectibles. Forty years, give or take, is apparently the amount of time it takes to shift from “dematerialization” to “materialization.”

A wave of restaged exhibitions is no accident. It operates in the context of a rising interest in contemporary curatorial practice (which many scholars credit Szeemann with defining) – and with it, a spike in research into exhibition histories. This makes a lot of sense: researching exhibitions means looking into the conditions under which art is shown and produced. Yes, we should think through the exhibition as a format: there is still a lot to say about the roles different kinds of exhibitions – solo, thematic group show, commercial versus nonprofit, international biennials, the list goes on – play in the production of art and establishing the value of artists and their work. But I would like to argue that we also need to rethink the way the artworld has established the exhibition as the central experience and means of viewing art.

2

One of the main ways we see art today is in a small square on a screen. Research begins online and it often begins with a series of thumbnails. Much of the contemporary experience of art is mediated via images, but somehow that does not constitute seeing art – because it’s done in front of a screen, because it means looking at copies of copies, because it does not involve a physical presence in an art space. “Art exists in a kind of eternity of display,” writes Brian O’Doherty in Inside the White Cube. He was right then and he’s still right. The question today is what could constitute “display.” (I relish how great this word is in this context because it’s used just as often to discuss art and screen technology.)

Technology changes the way artworks circulate. One day an exhibition could be sent to an institution via email. Scratch that, it already happened. A video file is sent for a screening program, a high-resolution .tiff is printed at a local printer by a museum. This is happening with more object-oriented mediums, too, and we’ll see more .stl files 3D printed as exhibition copies, alongside more editioned sculpture work. We are currently living through a much more substantial dematerialization of art than the one Lippard discussed, and among the primary responses of the artworld is rarefication. So any work that can be infinitely reproducible is sold in editions. A gallery’s letterhead on a certificate of authenticity is where the value now lies: Can there be a more dematerialized object?

These strategies of rarity prove that technology has yet to – cannot – cancel our object obsession. But what constitutes looking at these objects today? A curator or an art critic will be given a viewing copy of a video work by a gallery: Does that constitute watching the work? No, if it’s a video installation that requires a certain environment, or a multi-channel presentation. But much video work at the moment is narrative, single-channel presentation. We rent it from Electronic Art Intermix and Lux. We stream it on Ubuweb. We view it on internet platforms like Opening Times Digital Art Commissions, Vdrome (organized by the magazine Mousse), and The White Review‘s White Screen – though both White Screen and Vdrome only screen every given work for a period or a month or two weeks, respectively, abiding by the gallery system’s rarification mechanism by not making the work fully available. This is not a criticism per se: both platforms make a huge contribution – and it’s not a coincidence that they are organized by publications – in promoting new writing on moving-image work by commissioning essays in conjunction with the screening. The temporary presentation facilitates questions of rights acquisition, server space, and reproducibility; it translates the standards of the offline exhibition to sort through complex issues of online circulation.

Seeing art onscreen has become one of the main ways in which we are exposed to both contemporary and historic work. But viewing art is still defined by the gallery-dependent experience. Even with the rise of numerous platforms for the presentation of art online, there is still no rigorous criticism of work presented solely on the internet. And though I am not advocating for critics writing reviews of exhibitions based on installation shots, criticism needs to be expanded beyond the gallery. It hasn’t: though art viewers may feel that art can happen online, the significant conversation happens offline. It’s the belief that the event brings with it an encounter – with the work, with other viewers – that departs from the realms of immediacy, isolation, and insignificance (you’re supposed to imagine a single person sitting in front of a screen looking at an image of a cat) that are often associated with the internet.

We should resist the popular imagination of how art circulates online by emphasizing an overall understanding, and understate the installation-shot feed. The notoriety achieved by a site like Contemporary Art Daily is the result of the current status of the installation shot, presented as a quick, fix-all solution to the problem of sound-bite viewing online, like sites that post “an image a day,” divorced of all context. But the installation shot is too susceptible to cozying up with the art market: it values a white cube and work that requires only visual context (other work) rather than historical, textual, or performative material to accompany it. But to build a critical apparatus that responds truly to the way we see work online, the entire landscape of web-based engagement should be considered. It means that images, gifs, Vimeo links – and yes, installation shots, too – are all mechanisms that inform contemporary art. It means to discuss the web as what it is for contemporary art: a space for dissemination and production concurrently.

3

New York–based nonprofit Independent Curators International (ICI), whose mission is to produce exhibitions, events, publications, and research that posit the curator and his/her role as organizer at their center, began to circulate exhibitions in a box in 2010. Described in the press release as “charged with a do-it-yourself imperative,” each box is a collection of exhibits – small artworks, videos, soundworks, text works, ephemera, and archival matter – that could be packed up and shipped to art institutions across the world. Assembled by artists, curators, and historians, the boxes provide a cost-efficient point of access to the discourses that take place in the global artworld. (The first exhibition in a box, by the way, focused on Harald Szeemann’s Documenta 5.) That they centralize knowledge and deemphasize the individual needs of different institutions in favor of a well-worn product is negated by the idea that the ordering institutions can install the boxed exhibition at their discretion.

The exhibition in a box couldn’t have happened without a fight undertaken by minimalism and conceptualism – and largely won. The separation of the work from the object dates back decades: milestones like Donald Judd’s “Specific Objects” (1965), Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), or Dan Flavin’s use of store-bought material (and inclusion of instruction for their readymade replacement in case of a damaged fixture) allow for an exhibition of ephemera, of copies, of small-scale artifacts meant to circulate easily. What was so revolutionary about conceptualism is now flattened to become not “specific objects,” but rather, “almost-objects”: objects that depend on the exhibition space to define them as something worth looking at. To define them as art. There’s a lasting impact to this: the intellectual shift dissociating the art from the object defines the way we discuss contemporary art, and yet the importance of the museum as a site to validate the work as art has not been diminished at all. This is where Carl Andre meets Rirkrit Tiravanija’s pad Thai meets a certain urinal (or fountain) meets abstract painting. The reliance on the context of the institutional walls, floors, or screening rooms allows for easy recognition of the work as art.

There’s still work to be done with the exhibition format, but much more to discuss in what happens to art outside the exhibition space. And for that, we may need to discuss what happens after the exhibition. The term – call it “exhibition,” “show,” “presentation,” or any other synonym used to avoid sounding repetitive – communicates too little. An exhibition is basically an event: even if it’s on view for five weeks or three months (which seems to be the cookie-cutter standard for galleries and museums, respectively), most visitors will only see it once. This event-ness plays into the hands of the market. It allows for nonprofits and museums to show artists they cannot afford to collect (while enhancing the value of the work by way of institutional affiliation), adding the loan agreement from a private collection to the certificate of authenticity in the category of pieces of paper that assert and build value. Globalization has also played an important role in the financial aspects of the exhibition, especially where cultural tourism is involved (I am not the first to point this out in the context of the rise of international biennials), but also in the mushrooming of multinational galleries.

Exhibition histories, as a subject of research, relies on the importance and potential of looking at the exhibition as the context in which art is produced, but “the subject of exhibitions tends more and more to be not so much the exhibition of works of art, as the exhibition of the exhibition as a work of art. […] So it is true that the exhibition weighs in as its own subject, and its own subject as a work of art,” as Daniel Buren wrote in the catalogue for Documenta 5. Szeemann was criticized for asserting too much authorship in his Documenta. That curatorial authorship anxiety has not diminished with the widespread professionalization of curating as a practice of knowledge-production. The exhibition does have an important role as a space for dialogue but the arm-twisting to “generate meaning” – and to generate meaning at least four times a year of working in an institution – has created a highly regulated, professionalized curatorial practice that is marked by a pressure to produce exhibitions. And at times they feel like a tree falling in the wood: an event without viewers (save for an e-flux announcement that safely places it in a history).

Is the exhibition the best we’ve come up with? It would be very provocative of me to say, “let’s stop making exhibitions” and that’s not what I’m advocating. But there is a problem of overproduction of exhibitions in contemporary art. The internet will not be a solution to the overabundance of biennials, but it could be one space to engage with work that escapes the confines of the event. Curatorial practice has adopted the enhanced meaning the term has acquired as it has been distanced from “caring for art” and overtaken by “curated” wine lists. An expanded idea of curating is now understood to encompass much more than exhibition-making: it includes public programming, editorial work, educational initiatives, the curating of screening series, and so on. Maybe the exhibition needs to pass through a similar deflation as a term. Maybe once we see the term “exhibition” exhausted (as the overused “curating” has become in the last decade) we’ll see a way out of the event.

4

One of the iconic works in Szeemann’s “Attitudes” was Walter De Maria’s Art by Telephone (1969). It included a phone with a sheet of paper in front of it reading, “If this telephone rings, you may answer it. Walter De Maria is on the line and would like to talk to you.” It’s a work that requires an institutional setting (De Maria calling random numbers off the phone booth would hardly be the same work) and uses it, rather than relies on it: a daily object (phone) and activity (picking it up) morphing into a singular experience because of the set up in the exhibition. Art by Telephone rang on the opening night of the Venice version of “Attitude.” Miuccia Prada was the first to answer. The way I imagine their conversation, it began with – maybe after some pleasantries – De Maria asking Prada what the exhibition looked like. He would ask, though he already knows.

*

A version of this essay was initially developed as part of the conference “What is this thing called ‘exhibition’ and do we still need it today?” organized by Hila Cohen-Schneiderman at the Petach Tikva Museum of Art in October 2015. My sincere gratitude to Cohen-Schneiderman and Sky Goodden for their respective help in forming, shaping, and thinking through these ideas.

2 Comments