Joshua Schwebel is a Berlin-based artist whose work engages in conceptual and performative strategies of subterfuge. While a number of his projects have employed counterfeit, deception, and practices of “passing,” more recent works have focused on the visibility and valuation of creative and administrative labor within different artworld contexts. Some of these projects have proven to be contentious because they primarily focus on non-profit and public institutions that perhaps do not see themselves as holding the same kind of power as private, commercial galleries do. Under the microscope of social media, institutions have become anxious about appearing unethical, and certainly of attracting critique and controversy over same. Their reaction tends to diminish or avoid the serious dialogues that Schwebel proposes, pushing back against his provocations to their operating procedures. To give one example, as his final project, Subsidy (2015), for the Künstlerhaus Bethanien residency in Berlin, Schwebel used his entire exhibition budget to pay seven of the institution’s unpaid interns. A difficult but productive dialogue ensued after the institution initially reacted negatively to their HR practices being publicized.

Here Schwebel discusses one of his recent projects, which was set to take place at the Museum Reinickendorf, a small local history museum north of Berlin. Schwebel hoped to push the museum to critically consider their holdings related to the Nazis, especially considering the relative paucity of material they hold documenting a local Jewish presence. Upon receiving Schwebel’s project proposal, however, the museum shut down communication.

My dialogue with the artist, then, becomes a platform for the ideas that could not be grappled with there, and a parsing of this episode’s implications for museum practices, transparency, intervention, and Schwebel’s own practice.

I understand you received an invitation to work with the Museum Reinickendorf. How did they approach you, and what were your first steps in conceiving of a project for them?

I was invited in August 2017 by an independent curator, Dr. Lily Fürstenow-Khositashvili, with whom I had not worked before, but who had a good knowledge of my work. She was putting together a group exhibition titled Interventions for the Heimatmuseum Reinickendorf. Dr. Fürstenow-Khositashvili invited me to produce a new project in response to their collection.

I entered the project with a broad interest: I wanted to address the concept of Heimat, a particularly objectionable formation of German identity. The word Heimat, for Germans, evokes a bond to the German homeland, an internal longing (and sense of belonging) that goes beyond the legal terms of citizenship, and that can only be claimed or felt by (white) “German people.” The term and the way it is used implies a nostalgia for a time before Germany was “corrupted” by foreigners, immigrants, feminists, etc.

Unbeknownst to Dr. Fürstenow-Khositashvili when she conceived of the exhibition, the museum had recently changed its name from Heimatmuseum to Museum Reinickendorf, in an attempt to erase its ties to the contentious concept of Heimat, however this change was not accompanied by any changes in the content or structure of the collection. In a reverse, but parallel move, in February 2018, when I was formulating the work, Germany appointed its Ministry of the Interior as the “Heimatministerium.” This shift in nomenclature is also not merely semantic but can be tracked alongside an increase in right-wing violence attacking immigrants and refugees, and militant marches against the perceived diminution of the rights and privileges of white Germans.

The Heimatmuseum as an institutional construct expresses this nostalgia and the simultaneous kitschiness and conservative authority that accompany it. Heimatmuseums exist in smaller towns across Germany, and are often quite amateur in their curatorial direction, given that they were initially pedagogical tools used by teachers; they became ad-hoc repositories for local history and donated bric-a-brac, which district inhabitants considered of historical value. As a result, what’s on display is a vast assortment of quite unremarkable items, coerced into a quasi-historical timeline. The museum in Reinickendorf follows this model, and its permanent exhibition includes a “hunting room” with a variety of animal heads as trophies; a reconstructed thatch-roofed hut in the courtyard in which faded-pink mannequins are positioned to depict a “prehistoric” heterosexual family gathering around a fire; and a twentieth-century history room in which artifacts reflecting the district’s involvement in forced labor, the collapse of the Berlin wall, and the Nazi era, are displayed all together.

One large display plinth in this room comprised all of World War II, inclusive of artifacts of the Nazi party and its popular support. Along the bottom of this same plinth were taped Polaroid photos of the “Stolpersteine” (the brass plaques affixed to sidewalk stones marking the locations of the former homes of victims of Nazi deportation throughout Germany). These were the only visual representation of Jewish existence on display in the entire museum, despite its claim to represent the lives of (all) local people in the district.

In relation to the overarching concept of Heimat, and its underlying racisms and xenophobia, the room addressing the twentieth century was the most compelling. Contrasting the feeble display marking the extermination of non-Aryan Germans, two actual Nazi weapons had been excavated and sat on a display table. I was curious how the museum had acquired these objects that dated from the Third Reich, why and how they chose to display them, and what they might have in their archives that they didn’t, or wouldn’t display. So I asked to speak with the museum director, Dr. Cornelia Gerner, with these questions in mind.

What did you end up proposing to the museum?

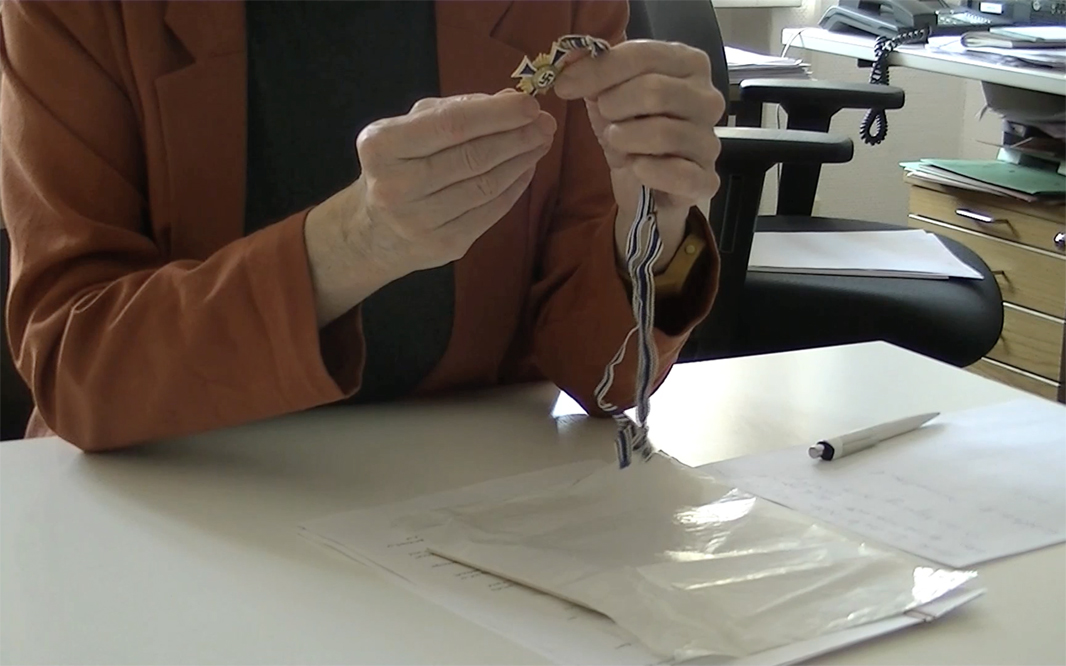

I planned to present a tripartite constellation of elements comprising a video, a letter, and a displacement. The video was recorded as an interview with Dr. Gerner and her colleagues holding various Nazi artifacts possessed by the museum. In it she describes the provenance and importance of each item, in what context they have been or could be displayed, and what the museum does not know about each one. The artifacts include an opera program from the time, daintily embossed with emblems of the Third Reich, which contains a text on the relevance of the opera to the ambitions of the Reich; a “Mutterkreuz” (Cross of Honour of the German Mother) given to women who bore numerous Aryan babies; a book of children’s songs, etc. Dr. Gerner outlines how most of the objects in the collection arrive there by donation and how their precise histories are often unknown. For her, keeping and displaying these items serves to educate – which, she asserted, was a political end in itself.

Just after I recorded the video, I wrote a letter to the museum director. In it, I proposed that the museum transfer one of its swastika-adorned artifacts to me – they could choose which one – on the condition that I would not photograph, display, or circulate it, nor would I sell or destroy it. My intention was to let it disappear from memory, to relieve the museum of its duty to preserve this horrible object. The letter questioned the value of historical conservation, which had been the main justification given by Dr. Gerner for the museum maintaining its collection of Nazi artifacts. In this, I was proposing a symbolic gesture of reparation: a single, small, but intentional absence as (inadequate) counter-balance to the paucity of historical commemoration given to the lives of Holocaust victims in this display.

Within the letter I indicated that the letter itself was to be a part of my exhibited work, and that correspondence from the museum, should there be any, would also be exhibited.

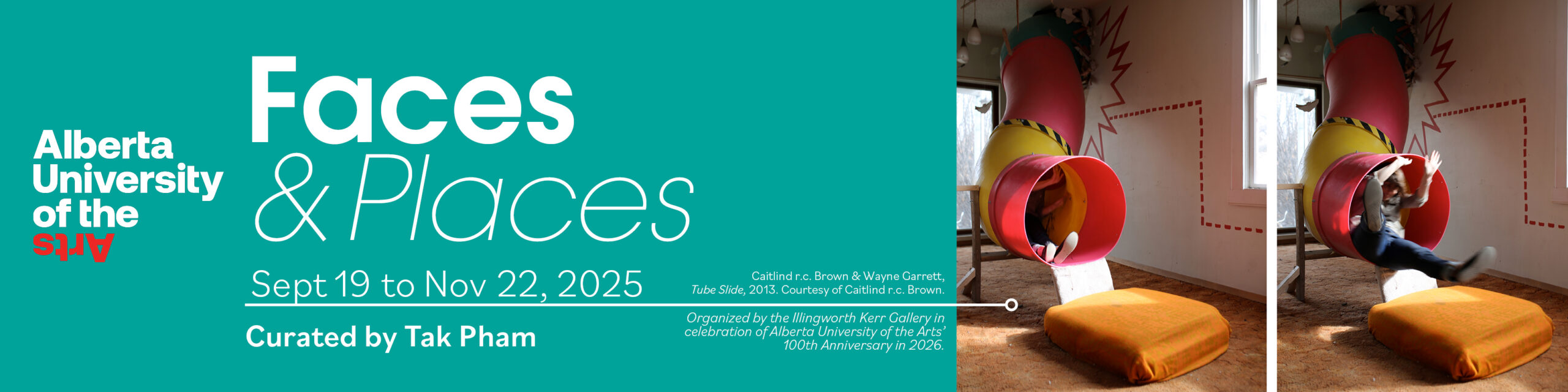

Video still of Dr. Gerner holding Mutterkreuz, from unpublished video interview at Museum Reinickendorf. Image credit: Joshua Schwebel, 2018.

What was the curator’s response to your proposal, and what about the museum’s?

I showed this letter to the curator before I sent it to the museum. She was enthusiastic about it, and thought it outlined a beautiful idea. With her approval, I sent it on to the museum. From that point forward, I have not received a word of response from the museum: all subsequent communication with them was mediated by the curator who would phone me to relay the museum’s demands.

The curator first conveyed to me that the museum wished for me to edit the video, which opened with an informal conversation between the director and her staff about the provenance and identity of an artifact in her hands. At the very beginning of the video, as the image fades up, we hear a voice saying in German, “Fur and pelts for what?” after which the group debates the dates of a Russian invasion. The video ended with Dr. Gerner saying, “I think I have said everything.” I was asked to remove these segments, likely to preserve an authoritative image of the director and the institution. However, these choices were deliberate; the work was intended to make the construction of historical authority visible. I replied therefore that I was uncomfortable with this request, and that I would not comply without any discussion.

On the heels of this, just days before the opening of the exhibition, the curator called me to say that the museum had made the decision not to respond to my letter, and moreover not to permit the exhibition of my letter. If I made the edits they requested to the video, they would permit its exhibition, framed by a text to be written by them. I do not know what they had in mind for this text, but Dr. Fürstenow-Khositashvili, the curator and only present proponent of my work, was also to have been excluded from the writing of this proposed text. I was outraged, and so withdrew from the exhibition, a decision I communicated to them by email, with, again, no response.

What do you think they were afraid of in the proposal? Did they communicate any of their rationale to the curator?

I learned from the curator that the museum took my letter extremely personally: the director’s feelings were hurt. She felt that she had been very accommodating by permitting me to undertake the interview, and was not prepared for my letter. Over the course of my research incursions, she and her staff repeatedly asked why I was focused on this particular subject in their relatively small museum. They once asked, “Why not go to Poland? They are much worse.” One particularly revealing detail that I heard from the curator was that they were deeply offended that I expected them to “justify” their collecting, preservation, and display procedures. And yet, they are a public institution! Which means that they are already and inherently accountable to justify their process with or without my provocation.

My project gave them options that would have required a politically vulnerable commitment on their part, but, if taken sincerely, proposed a radical approach to museum preservation and collection of artifacts of genocide. Sadly, they were afraid of entering this debate. Moreover, by shutting out the work of the only Jewish artist invited into the exhibition, they reinscribed the very antisemitism from which they intended to distance themselves. Ignoring and shutting down my work – in a way that is intensely delegitimizing and disempowering – silences, yet again, a Jewish perspective that is lacking in this particular museum, and more broadly, silences the perspective of non-German foreigners excluded by the Heimat ideology.

Can you discuss the context of this project in terms of your work, and museum practices in Germany and beyond?

The preservation and provenance of cultural objects is deeply political. The authority to give an account of “what happened” goes to the victors, who claim the legitimacy and credibility of History, along with proof in the form of artifacts preserved in museums entrusted with authority. The people who faced extermination by the Nazis, as in other genocides and displacements, struggle to assemble evidence of their existence, their culture, and their heritage. They must cobble together their histories by sifting through fragments and absences. In my work I wanted to traumatize the museum in return; to impose a lack around which they would be forced to remember, and to experience what it is like to give an account through that absence.

There is a specific and troubling silence around antisemitism in Germany today. Those who might wish to express it are frustrated that there is still so much shame attached to German nationalism, and they feel that, having publicly addressed the crimes of Nazism, they should no longer have to “deal with” the issue. Coupled with rising nationalist sentiments, the resistance to sustaining an open dialogue on living forms of antisemitism, expressed as xenophobia, violence against refugees, or institutionalized racisms, is troubling.

My work intentionally put the museum in a position with no clear directive for how to respond without facing public outcry and potential accusations of antisemitism. If they refused to give me an object, they were defending a decision to keep extremely contentious objects in their collection, and would need to carefully justify this. If they agreed to my offer, on the one hand they could embrace a radical gesture towards re-signifying the political weight and responsibility of their collection. On the other, they would need to address all of the hurdles and accusations that face a deaccession process in a public museum (and I imagine these are dense, given Germany’s love of bureaucratic protocols). Furthermore, what would it mean to relinquish a swastika to me, just because I asked? Could they just give their collection away piecemeal to whoever put in a request? How would they answer to the families who had bequeathed them these objects? If I had been a German, or a person of non-Jewish descent, how would the significance of my request be shifted?

Nonetheless, I did not anticipate that they would refuse to exhibit the letter entirely, opting for censorship and avoidance. This silence and silencing expresses the level of anxiety provoked by my letter. It reveals how threatening they imagined the proposal to be: so much so that even making it visible – without replying – exceeded their capacity.

I was, and still am, interested in poking holes in the justification that “historical value” trumps accountability, when accountability means situating a collection and its objects transparently within the broader social and political contexts in which museums operate. The provenance of many objects in German museums is theft and murder through colonial genocides in Africa, the lesser-known precursors to the horrors of the Holocaust, which itself also provided significant bounty to Germany’s cultural holdings.

These systemically stolen artifacts remain proudly exhibited in the largest and most renowned cultural institutions in Germany, such as the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, despite sustained demands for transparency and restitution. Situating my aborted gesture in terms of property relations and in the context of the inequities underpinning German collection practices, my attempted extraction acquires more significance. Dr. Fürstenow-Khositashvili, the curator, relayed to me that the assistant to the director at the Museum Reinickendorf attempted to belittle my work, commenting to the curator that “all the other artists brought things to the museum, while he only wanted to take things away.” The hypocrisy (and antisemitism) of this comment really grinds at me, considering the larger and more contentious thefts constitutive of the majority of German museum collections.

Where do things stand with the museum now?

Not good. I haven’t received any direct communication from them since I sent the letter on April 16. I heard through the curator that they have no intention of paying me for my work, despite having signed a contract with me. I have reached out to a lawyer from the Berlin artist’s union, who has agreed to represent my case, but the outcome of this is still pending. I doubt that I have the leverage to make the museum care or reflect on their conduct, which is a shame. I don’t think they took my work seriously. If I could, I would propose a public discussion with the museum, positioned within the broader context of other institutional interventions and critiques of collections.

The museum, as an institution of memory framed through Heimat, is a constellation of state-authorized power and visibility that elevates a particularly ad-hoc form of memory production to the status of History. To attack a museum and hold it responsible for the decisions of a larger system of colonial and genocidal power is perhaps conflating one entity with another, but the tendencies of institutionalized power to contort, disguise, and rename itself, while employing the same techniques and passing along the same authoritarianism, is very real. Confronting institutions through reflections of this behavior is an important part of my ongoing practice.

Joshua Schwebel is a Canadian conceptual artist based in Montreal and Berlin. Working in conceptual art and institutional critique, Schwebel has presented his work internationally and across Canada. He holds an MFA from NSCAD University (2008), and a BFA from Concordia University (2006). Schwebel’s current and recent projects include exhibitions at the Darling Foundry, in Montreal; Hamburg Photo Triennale; and the Biennale Nomade in Santiago, Chile.

1 Comment