Agnes Martin began her lecture at Yale University with a deep breath … slowly, in and out. It was the mid-1970s, and Martin (1912–2004) was in the middle of a major resurgence in her decades-long career. “At last,” she declared, “we are in the midst of reality, responding with joy.” Another long silence. Her lectures were never, and always, about art.

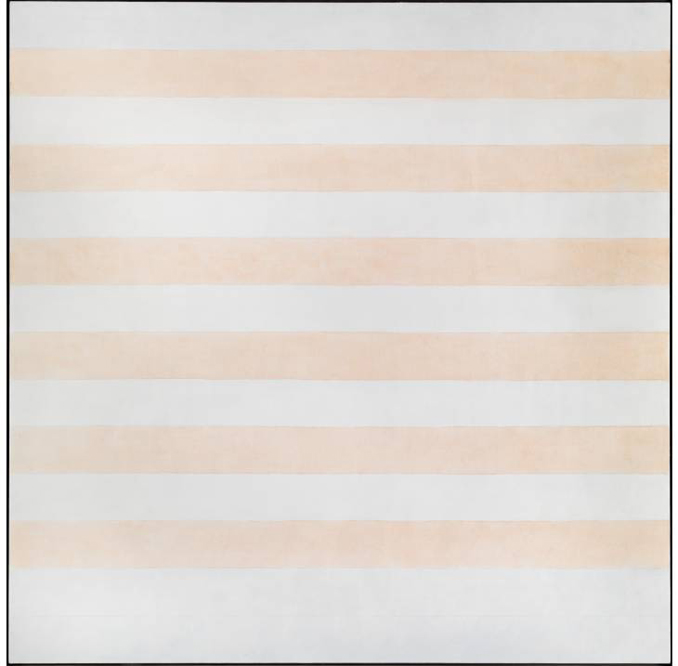

From the time of this lecture until her death in 2004, the titles of her paintings often conveyed a joyful utopia: Fiesta 1985; Happy Holiday 1999; Loving Love 2000. In this phase, her six-by-six-foot canvases generally featured horizontal bands of various proportions, most often in white and/or with different combinations of pale, primary hues: coral, morning sun, sky. Over time, she explored some variations in her compositions and palettes. Her canvases shrank to a more manageable five-by-five feet as she aged. But her main theme remained an unalloyed upliftedness: she once said she had spent ten years painting “praise.”

Martin did not always paint in pastel colors, nor were her titles always so celebratory. She trained in portraiture, landscape, and watercolor at the University of New Mexico and Columbia University Teachers College. Gradually, she extended into allegorical and biomorphic abstractions, and New York gallerist Betty Parsons found the latter so strong that she bought enough to finance Martin’s move from Taos, New Mexico, to New York, in 1957. Her career solidified over the next decade. She lived in a community of artists between the skyscrapers and the shoreline of lower Manhattan. In addition to drawings and paintings, she created assemblages with patterns of nails and other local materials. She began working in two consistent sizes – twelve inches square and 72 inches square – and her art became progressively reduced in its abstraction. First, paintings of shapes with crisp contours; then, all-over fields of ruled horizontal and vertical lines.

Martin claimed that her breakthrough occurred when she was thinking about trees and about “innocence,” one of the joyful “subtle feelings” she sought to concretize in her work. Her studio practice involved waiting, trying to become calm; when a grid came into her mind’s eye, she created the six-by- six-foot The Tree, 1964. The composition features rectangles of ruled pencil lines in addition to paint. It “satisfied” her because it evoked the innocence of trees, yet did not resemble anything. This aesthetic of ruled rectangles on a square canvas became the first phase of her mature work. Many of her grid paintings from the mid-1960s have nature-based titles, though a perennial favorite is Untitled.

How does joy emerge from repetitive geometry? First, the paintings emit light: it is cheering to see an inanimate object glow. In her later phases, if a color looked too heavy, Martin would lighten it with a layer of white wash to make it luminous. If a color wasn’t resonant enough, she would add another thin layer of paint, or slash and trash the painting. Her eye was impeccable and uncompromising; her dealer deemed her the greatest artist-editor.

Second, Martin’s lines and bands are not hard and harsh, making the work invitingly human. Though she used a ruler (or string, early on), and sometimes masking tape to create a clear edge in paint, the straight lines register the vibrations and agitations of the artist’s hand and inevitable divots in her attention. These rough-around-the-edges effects draw upon years of building houses, installing plumbing, splitting logs, fixing cars, gardening, swimming, and sailing: her touch is precise without being fussy.

This inviting mutability occasions a third source of joy for the viewer, which comes from the dance of different distances. Viewers generally begin at a standard distance from a Martin painting, then draw closer to puzzle over the details. Eventually, the desire grows to step far back for a more holistic view. Each position yields new perceptions of space within the painting. It is refreshing to discover that such simple compositions can offer ever-changing visual experiences, from a haze to a wall to a window on to deep space.

These are subtle joys – founded in basic sensory perceptions, not dramatic feelings or narratives – and the evenness of Martin’s compositions makes the effects dependable. She imagined that people could view her paintings for ten minutes upon waking up each morning, to begin the day buoyantly. To make this experience more widely available, she also created a feature-length film of a boy hiking to the sea, Gabriel, 1976. This beauty-seeking, contemplative alternative to overly sensationalistic Hollywood films did not fare as well as her paintings, but it’s still interesting to see.

Altogether, Martin’s work offers a counter-culture aesthetic, an antidote to daily distractions. “We are in the midst of reality,” she once said. She knew reality included distress, disease, even destitution.

Martin was born in 1912 on a rural Canadian farm. Her father died in 1914 and soon her mother moved the four children to Vancouver, renovating houses and running a boarding house. A grandfather was an ally, but Martin weathered her mother’s neglect and even antipathy. In Taos in the 1950s, the artist would endure extreme poverty, when she lived in her dirt-floored adobe studio.

As an adult, her sense of reality was complicated by schizophrenia: she often heard voices and occasionally saw characters that did not exist. Though these experiences were not always negative – she consulted the voices for guidance in her life and art – her illness required medical management. Martin also managed herself well: she painted when healthy, and retreated when she felt incapable of socializing. So in 1967 she left New York, roamed in a camper van for 18 months, then settled atop a mesa near Cuba, New Mexico. She began painting again after she built a studio.

The silence of the New Mexico desert is total – and restorative. Though Martin traveled widely, she lived in New Mexico for the rest of her life, and maintained intense privacy. In elliptical interviews, she’s obscured her personal life and mental state. Our challenge is to fathom her accomplishments in light of her challenges: perhaps “responding with joy” is a wishful framework for the way things could be. We can now examine her artistic contribution in light of what is possible to know about her life. Though this summer’s Tate retrospective will be her third, it will be the first after her Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 1997.

Museum visitors often glide slowly through the rooms of an exhibition, but Martin gave a human scale to her paintings so that each would feel like a room of its own. Try stepping into one (figuratively) … take a slow breath, in and out. How might Martin’s minimal structures of abstract expression act upon you? Do the dance of distance. See if the steady tremors – and the constant mutations – in her work summon you to experience your subtlest sensibility. Perhaps that feeling is, itself, joy?

This feature was first published in Tate Etc. (Issue 34, Summer 2015) with the title “Square Dance of Joy.” Momus is engaged in a partnership with the publication.

When I started collecting art pieces, I was really trying to find On the Subtle Joy of Agnes Martin. It was one of the first pieces which made me gain an interest in art collection.