Twice in the past year I’ve visited Olga Korper and she’s taken me from the gallery, past the offices, through her kitchen (where there’s usually a smoking ashtray, a cappuccino, or a tray of sweets sitting out, all talismans of her unique brand of old-school sophistication) and into her living room, where we stand before one of her favorite works of art. We stand there quietly and at a distance for a moment. We are conspiratorial, and willing. Finally a white shelf slowly expels a drawer, the mechanical “whir” of it like a question that’s still thinking. It comes to a stop, fully open, though it does feel like a halting stasis. And then, of course, you step towards it, and the drawer quickly retracts. It’s a kept secret, a wink and a nod, a bit of artful engineering, and a perfect example of Lois Andison’s ability to harvest feeling from performative sculpture. This one has you feeling curious, then rapt, then tickled, then a little admonished. And if you stand there another beat, the drawer (2012) breeds a certain despondence in you, too. Another desired thing proven to be just out of reach.

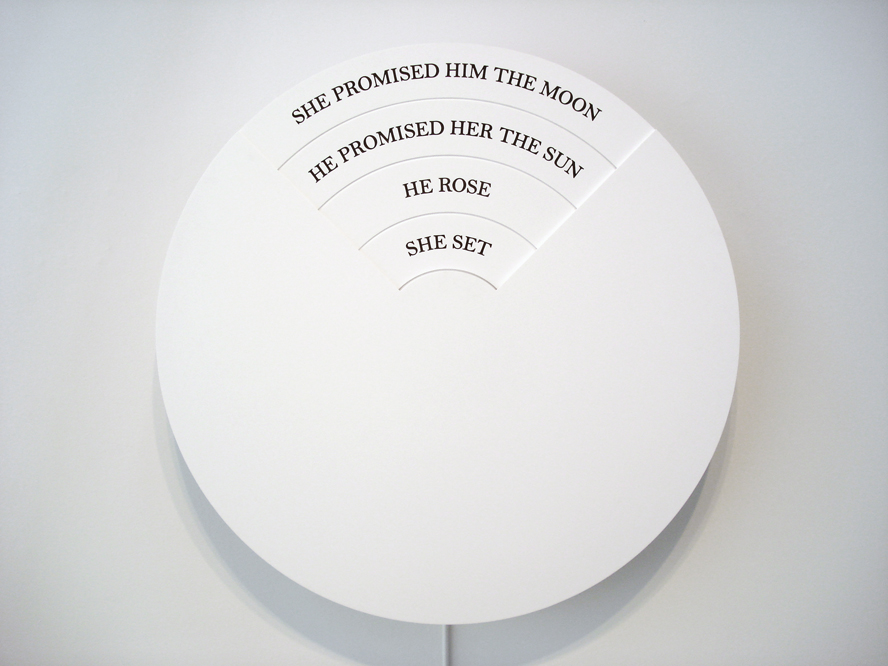

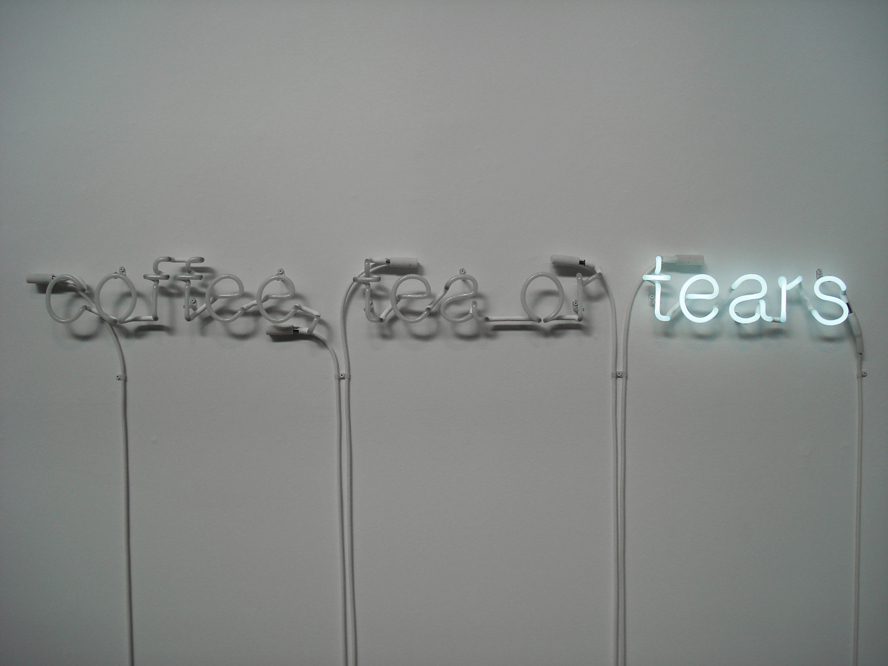

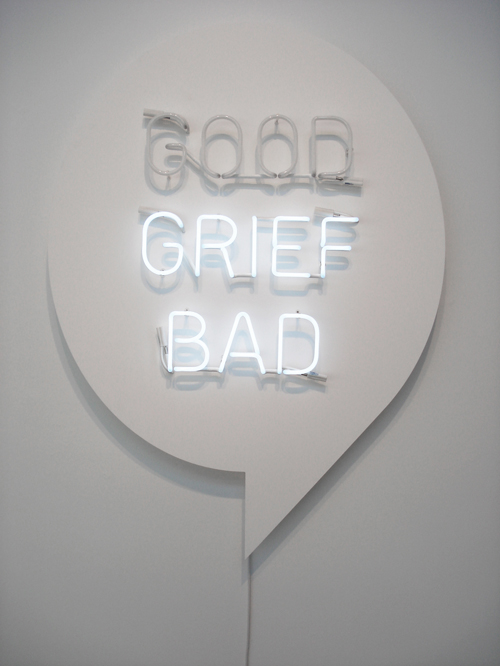

Andison’s fall exhibition at Olga Korper Gallery, text, combs, wheels & poems, communicates a lot of feeling in this way. Her signature word-play and absurdist wit continue to move white-washed kinetic sculptures, and innervate the room with presence, and our unsettled want. However, here, showing recent work (some of which was recently exhibited in three simultaneous shows in Fall 2014), Andison adds to her typically vulnerable, chattering, and longing sculptures the hum of a historical communiqué. Centered in this spare show is a significant kinetic sculpture titled nudging marcel (2014), its erected bicycle wheels spinning in place and mirroring one another’s side-to-side leaning like floating quotation marks. Two white stools ballast its comment. This is an afterwork, Andison’s series of sculptural homages to modernist male artists. Man Ray has been corrected, Picasso has been softened, and now, with unusual assertion and directness, Duchamp has been delivered a meaningful nudge.

Korper termed Andison a feminist when I asked about her larger practice, and the recent work sustains this. However I’ve always found it searching when feminism asserts itself through speaking to established men. So I called Andison for a conversation on her afterworks, and the feeling of her work. She demonstrated both vulnerability and self-knowing.

In talking to Olga about your work, she described your practice as often carrying notes of melancholy. I wonder if you would agree with that. Because certainly you’re communicating a sometimes absurdist or ludic quality, as well. But there’s a razor’s edge between these emotional spheres in your work. Can you reflect on the feeling of your practice?

I always say that there’s a sense of loss in my work, and that’s something that I realized very early on, and I’m not sure how to lose that – how to lose the loss. I don’t know if it’s possible. And maybe that’s what people think of when they say melancholic. I think for whatever reason we have something within us that, no matter what we make or do, there will always be a presence. And if I was to say that there would always be a presence [in my work], it would be a sense of loss. The work is delicate even though it tries to assert itself. It’s a precarious delicacy that reinforces that sense of loss. Melancholy and loss sit at the same table, and I don’t think it’s something that I can explain. It’s embedded and not something I think to do.

A strong through-line in your practice in recent years are these “afterworks” that speak to iconic male Modernists. Where did this series stem out of?

It was the trophy after picasso. [The piece] had kind of evolved out of working with a bicycle in a three-channel video that I ended up collapsing into one timeline. After working a lot with the bicycle I had all these objects in my studio – I had wheels, I had handlebars; I had been customizing each bicycle to each experience, and so looking at these different parts, I started to think about Picasso’s bullhead (Bull’s Head, 1942). For him it was relational. He puts the parts together not because he went out searching for them, but he simply had them around.

In thinking about kinetic sculpture and about his piece, I thought about how I would approach it [if I were to make it]. I was thinking about this idea of responding to male Modernist artists. I had wanted to bring women back into the context, so I put a Georgia O’Keeffe flower in the center of the bicycle seat, in the sweet spot. Then, when I was working on the large mobile in response to Man Ray, I was thinking about wanting to liberate the hangers, and how that’s a very female response, I thought: wanting to take care of the impasse, to cure the impasse, to want to let every piece within the mobile live freely. I started to think about it in a gendered way. They’re all performative, they’re all playful. However, the title with marcel is quite direct, this idea of nudging him to respond, or nudging him out of the way.

What are the limitations of speaking to men in order to assert feminism? Has it ever troubled you or been antagonized by others that to persist in making those references you’re perpetuating these dominant male presences in the canon and in the contemporary moment?

I think it definitely could be interpreted that way. Why re-make the work of a male modernist artist? For me, I think the work I’ve always made has a certain amount of vulnerability in it. When I was making the piece that was very masculine, very machismo, the bull’s head, I was thinking about how you can make that object vulnerable. So even if the source is coming from a male modernist artist the intent is to destabilize it from that position of authority. I don’t think it entered into my consciousness that by re-making the work I’d be positioning these subjects on a pedestal or anything.

There’s obviously a secondary position that’s sewn into the afterworks term, though; you don’t mind responding, rather than asserting? How do you reflect on this aspect?

I think with any homage you have to be in the position of coming after. This is part of my respect for the work that’s come before. I guess marcel is a very literal translation of his work, but with man ray, you’d have to know your art history to know that piece, it’s so far removed formally, because I’m not using a readymade. I don’t mind that it might feel subservient; it’s a call-and-response. When you begin a conversation with a work, your work comes after – whether you’re playing with it or transforming it, or flexing it in some way.

What strikes me is the uncanny way in which you invoke a presence in your work, and I don’t mean these modernists you’re speaking to. You have an exceptional way of conjuring the presence of a person or a spirited thing through your work. How have you been able to do this, and is it something you’re consciously attempting?

It may sound really simplistic but it just hit me this year that kinetic work is performative. So in many ways, the work has a presence through performance. It’s not static, and has a different way of opening itself to the viewer. [I think it also helps] that the mechanics are hidden; there are few times that you see what’s making the work operate. Sometimes ninety-percent of the effort is in trying to figure that out. It puts the piece back in the realm of sculpture that has some kind of presence that will be advocated through the viewer or on a continual basis. The idea of keeping within the domain of sculpture rather than trying to take it into the world of mechanics or technology is really important to me. I’m always declaring myself a sculptor. When the piece comes out of a sculpture wanting to do something, [the technology] becomes more subtle.

On that note, you show threading water, here, a video work where you have a very human presence [artist and actor Lisa Birke] filling the screen, and whose presence is informing the entire exhibition just through audio alone. Was there any insecurity or vulnerability in choosing to interrupt a room full of more engineered or kinetic presences with a real body?

Early on, that piece was created for a series of shows at the Doris McCarthy Gallery, the University of Waterloo Art Gallery, and Rodman Hall Art Centre [in 2014]. And Marcie Bronson, the curator [for the Doris McCarthy exhibition], asked for work that physically had to do with the body, to counter the presence of the kinetic work with something that was more in real time. When I made that piece, it was very much about a sculptural experience in the landscape, but it had a timeline, it had a narrative.

I had a lot of anxiety about bringing that really female presence into what I thought may be – because marcel was so dominant – may be a more masculine reading, and how to make those two live together. I had to trust that the work could function together because it was made by me, and that one work could lead into another. Because there is a lot of vulnerability in each piece, I think. Even marcel.

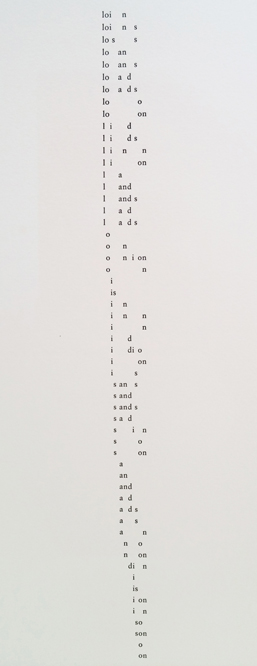

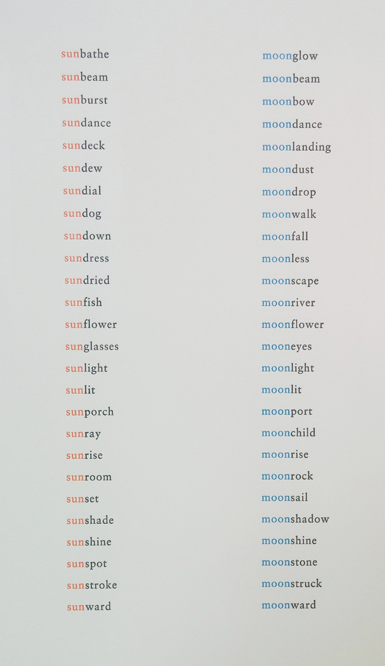

I’m curious about meaning. There’s a nice point in Jonathan Shaughnessy’s essay [in Andison’s forthcoming catalogue] where he arrives at an essential component in your work, which is your play with words and their finite potential for meaning. He writes, “within a contemporary context in which theory has run with language’s apparent ‘arbitrariness’ into a sea of untethered conceptual undecidability and ambiguity, Andison’s work proposes a limit to both the movement and meaning of things.” Shaughnessy suggests you are working within a close spectrum of possibility, in your work; is this in fact your desired comment?

Cerebrally I agree with Jonathan. When I work with language the words are both temporal and fixed – they exist through movement that is time-based but they exist within a closed loop. We could see the closed loop as finite if that is where the work stopped but it doesn’t because the production of meaning is passed on to and through the viewer.

1 Comment