If we are to believe artist Hito Steyerl, then ours is an age of planetary civil war. With conflict distributed across the globe, there’s a lot about the contemporary we might want to escape. For some, science-fiction is the lifeboat to new worlds beyond our immediate reality. But the most sophisticated science-fiction is always about the here and now; it defamiliarizes our experience of the present to make what we think we know strange. Many artists like Cao Fei, Amy Brener, and Steyerl have embraced art’s world-making potential to suggest alternative localities, modes of production, and politics. Current or recent exhibitions like the 11th Gwangju Biennale, titled “The Eighth Climate (What Does Art Do?),” and the 20th Sydney Biennale (“The Future Is Already Here – It’s Just Not Evenly Distributed”), function like seismographs, conglomerated readings of the present to ultimately explore art’s capacity to redirect our future.

Ajay Kurian is one such contemporary artist who uses eclectic materials–gold-plated ostrich eggs, gummy bears, and vaporizers – to postulate new worlds without leaving ours. Since 2015, the 32 year-old has had four solo presentations at JOAN in Los Angeles, White Flag Projects in St. Louis, Rowhouse Project in Baltimore, and Art Basel Statements, and was also featured in the most recent edition of MoMA PS1’s Greater New York. In our conversation, we discuss his vision of a future long since passed. Kurian also speaks to the unlikelihoods or anomalies in his emerging career: being brought up in an Indian family in white suburbia, and making a career without an MFA. His solo show, The Dreamers, will be on view at 47 Canal from September 10 to October 16.

For me, one of the first great revelations during our studio visit was learning that we grew up in the same zip code, in Lutherville, just north of Baltimore. We went to rival high schools only a few miles from each other on Charles Street. The otherworldly, the empyrean, the idiosyncratic materiality, all of these deeply mysterious aspects I find in your work actually have some connection with a suburban banality I knew all too well. Can you share a little bit about these experiences, growing up on Falls Road and going to Gilman, and how they might have entered into the work? I can’t help but think they echo.

A part of me feels this to be a leading question, as if because of your recognition, there must indeed be a connection that links suburbia to my work. I don’t have much to offer in terms of a connection that feels easily manifest, but I can say that I don’t know how to discount my experience.

I think that’s a fair response. I suppose I’m looking for a way to better understand the uncanny sense of place that your work emits.

I did grow up in suburbia, one that was white and affluent. I came home to parents that were slightly lost in a country they wanted to adopt as their own, but struggling to figure out how. I had friends that would address my parents respectfully while asking me later how long they’ve been in America because their accent is so strong. Those friends would occasionally turn down food because it was too unfamiliar or worse, unappetizing. I would see my cousins and grandparents in India every other summer and feel the intensities of experience there. So much so, in fact, that I would dream about tastes, smells, rooms, and drives after coming back home. And despite feeling at home there, I was still foreign in India, still a bit distant, still unfamiliar. I think there is a part of me that felt and feels a bit other in every environment. Not in an isolating way, but in a way that gives me access to a slight uncanniness.

So you feel that this tension between places, rather than the experience of being in any specific locale, was actually more formative?

It’s also because within most contexts, I found myself feeling safe. Being able to encounter various environments without fear is certainly one of privilege, and that colors my early understanding of the world as much as it might elucidate what I find interesting, appealing, or awe-inspiring. I can say that comfort is something I was lucky enough to have from an early age, and this tension between comfort and discomfort continues to play a role in my work. In some cases, however, discomfort found me, and in other instances, I sought it out. I think biography might be a better conversation for us to have privately. Simply put, my full sense of place was never dictated by 21093 alone.

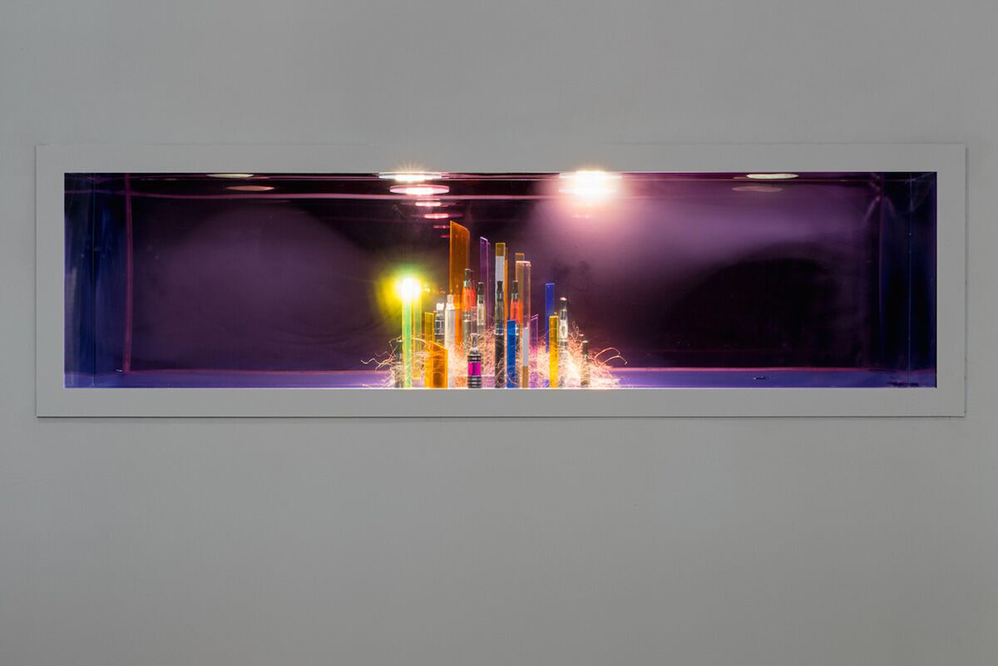

View of “Comfort Zone #3 (Heaven is for smokers and non-smokers alike),” 2014, Artspeak, Vancouver. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Courtesy 47 Canal, New York.

View of “Comfort Zone #3 (Heaven is for smokers and non-smokers alike),” 2014, Artspeak, Vancouver. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Courtesy 47 Canal, New York.

There’s something science-fictional about your art – transportive, even. But I feel like it’s important to be fully cognizant of the fact that what we’re looking at – as otherworldly and uncomfortable as it might appear – is always of this world. But what you take from the world and recombine in baffling ways leads us to a new temporality, a new future long since passed. How do you characterize this aesthetic, this feeling, or sense of place? Specifically, I’m thinking of works like Comfort Zone #3 (Heaven is for smokers and non-smokers alike) (2014), a vitrine of vaporizers and fog, gleaming and glowing like Manhattan’s skyline.

It’s hard for me to characterize because it’s often simply what feels right, but I think your phrasing is accurate. There is a feeling of a “new future long since passed.” I think what appeals to me is when the signification of the future butts heads with the actuality of its datedness. With regards to Comfort Zone #3, I suppose the sense of place was meant to feel precisely otherworldly and immediately familiar, because this is very often the logic of advertising. It keeps you from feeling estranged from a product, while still suggesting that it can take you elsewhere.

The whole culture that has emerged with vaping is so designed and carries a particular aesthetic. What attracted you to this pseudo-sci-fi consumer culture?

E-cigarettes and vaporizers came on to the market rather quickly and were adopted even faster, which caught my attention. A market was being developed right before my eyes. Advertisements, stores, and “lounges” were popping up and I noticed people “vaping” without any qualms at all. The fact that we had to extend our language for this product is a testament to its immediate embedded-ness in culture. It seemed to me that there was the hope that e-cigarettes could be the “healthy” cigarette, or the no-guilt cigarette. They promise the feel of a cigarette without any of the obdurate matter or consequences. It was as if people felt they could have their immaterial cake and eat it too. At the heart of it, for me, was a desire to dematerialize into the future. The obvious and near idiotic paradox, of course, is that there’s a whole lot of “stuff” necessary to dematerialize, and the most immaterial things are still made of “dumb stuff.” A thread of this can even be found in Medieval thought. The continuity is there, the religiosity and belief are there, and the paradoxes abound.

It’s kind of brilliant, with the lounges and “e-liquid” and everything, how one could become a middle-brow connoisseur of discerning taste and experience. That being said, is there something too accessible (or “comfortable”) about Comfort Zone #3? Because of vaping’s ubiquity, there’s something immanent for viewers to latch onto.

I don’t really think about a piece as being “too accessible.” If it doesn’t work for me as a sculpture, then I’ll have my reasons, but accessibility doesn’t explicitly come to mind.

Aren’t you worried that vaporizers, because their culture is so designed, will feel obsolete all too soon?

The vaporizers might be a trend now; they might be ubiquitous and a part of culture in such a way that gets too close to tacky, but that’s going to pass, and they will become relics. Regardless, I think formally the piece worked when it was first shown, and it’ll work 20 years from now. How it’s perceived and received will of course change. In the end, it doesn’t come down to accessibility, it comes down to achieving a balance that seems suitable to me. The variables involved in that balancing are too numerous and contingent to list, and they’re often so intuitive that to sit down and think through every move would be grossly surgical to me.

“Sunshine,” 2013. Bronze plexiglass, lamp, melted gummi bears, paint, gravel, pop rocks, spit. Courtesy 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

“Sunshine,” 2013. Bronze plexiglass, lamp, melted gummi bears, paint, gravel, pop rocks, spit. Courtesy 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

How does Comfort Zone #3 compare to Sunshine (2013), your other work that was in Greater New York at MoMA PS1? That piece seemed to cloak its materiality.

With Sunshine, it was the materiality, which became a conduit for thinking about a number of things. But this eventually took a backseat when I started to see what really made sense for the sculpture. Initially, I didn’t conceive of the translucent column, but over time, I realized that the piece needed another step of mediation that would allow it to become different things, make you feel different things. The materiality became almost textual because you couldn’t smell it or get up close to the gummy-bear sun. Materiality was just an idea behind Plexiglas.

I’m curious about your decision not to attend graduate school. It would seem much more difficult to break into the New York gallery world without an MFA, not to mention the professional network and possible prestige that comes with it. The MFA is almost a rite of passage for a contemporary artist. Why didn’t you go to graduate school, and what advantages or disadvantages did that decision afford you?

Well, it’s hard to say it was a decision.

What do you mean?

I did in fact apply to graduate school right after my undergrad degree. I just didn’t get in anywhere.

Why do you think that happened?

My work was scattered and it felt too theoretically bound. Of course I was pretty beat up about not getting in, but in the end it worked out. I ended up seeing how a lot of different parts of the art world operated by working at a magazine, a museum, a gallery, and a studio. After I started my own curatorial project, Gresham’s Ghost, I didn’t see the point to going to graduate school. I was learning by doing and making mistakes. And regardless, I was lucky that I went to Columbia for my undergraduate degree.

What about that experience was meaningful to you?

Most of our classes were with graduate students, so I befriended many of them during my time there. They say graduate school is for making connections, but at Columbia, it was just as well part of your undergraduate education if you wanted it to be. You spend enough time with the grads that you can see how they work, learn from them, and keep in touch. It was hugely beneficial from that perspective. I can’t really think of any disadvantages for me, but I imagine that if you don’t have a network of people during your undergrad, then it’s difficult to figure out where to go or how to start. Finding one’s community is really important. If it takes graduate school to do that, then so be it, but very often it can be found in other ways. Let’s be clear, though, these “name brands” certainly help. It puts you in a network of people that already have a bit of a leg up. I mean, none of the people that come out of these schools are guaranteed any kind of success, but the chances are better. If you went to a state school and are trying to break into the artworld, I’m sure it’s a different story.

Could you elaborate on how Gresham’s Ghost might have functioned as a surrogate for graduate school?

Gresham’s Ghost was a roving curatorial project that I started in 2008 and ran for about four-and-half years. I had a website, business cards, a brand, all that. I simply let it fade away. Sometimes it’s good for things to get lost in the shuffle, and not because they were bad ideas or shouldn’t be remembered. I just wanted it to fade away for a while. We’ll see if anything comes of it in the future. I did a series of shows, some I curated myself, others in conjunction with other artists and curators like Josh Kline and Bob Nickas. In situations like that, I was more of a facilitator than curator, though we exchanged many ideas and I learned a lot from both of them during our time working directly together. These projects made me the artist I am today.

How so?

The way I think about and through objects, signs, suggestions, language, feeling, atmosphere: it was all heavily influenced by putting those shows together. Realizing all the intense variables involved in putting up an exhibition, as well as sympathizing with those who do it for a living, has given me a different understanding of what those jobs entail. There are people who call themselves curators, or something of the like, that don’t really have any sense of how to put up a show. The material facts of exhibition-making are just as important as the ideas that circulate within them.

“My Busy World (Joy leading Sadness),” 2016. Aluminum, polyurethane, fake rabbit’s feet, steel, spray paint, 3-d printed cereal, foam, epoxy clay, sharpie, duct tape. Courtesy 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Julien Gremaud.

“My Busy World (Joy leading Sadness),” 2016. Aluminum, polyurethane, fake rabbit’s feet, steel, spray paint, 3-d printed cereal, foam, epoxy clay, sharpie, duct tape. Courtesy 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Julien Gremaud.

Since Comfort Zone #3, how have your conceptual preoccupations shifted? I find My Busy World (Joy leading Sadness) (2016) particularly alluring because I, and perhaps many other people, have vivid memories of playing with such contraptions in a doctor’s office or school.

Regarding that particular piece, which is a rather complicated one, I suppose it started as a kind of portrait of the character Joy from Pixar’s Inside Out. Joy acted as a kind of emotion police in the film, or better yet, a character who policed normativity. She wanted to make sure the child wasn’t too much of this or that. The child must be just so, just normal enough so she fits in, so she’s happy, so she has a good life and gets a good job. What depressed me about the film was that the child’s mind was turned into a bureaucracy. It was Office Space for kids.

When you put it that way, it’s rather dystopic. It’s strange and unsettling to think of this kind of affect-management being administered to children by Pixar.

The film prescribed a way to create a future worker who would know how to keep things under control and manage their emotions. The game that I used as a model for the piece felt appropriate because it was a game to busy yourself. It wasn’t very fun or interesting, it was just there when you had to kill time and smart phones weren’t invented yet. They were the toys you played with in the office. Before pushing paper – push these wooden knobs.

And, to what end do toys and games become useful metaphors for art, if they are at all?

I don’t think toys and games are metaphors for art. They are specific for me, not something that I would generalize into a way of making or thinking. They do and speak to many things. What is important is how I can get them to speak to or aid the atmosphere I’m interested in making. Metaphor is useful when it can be both specific and leave you with the sense of something larger. But when you’re asked to find the borders of that larger something, you’ll be hard pressed to find them.