Six months ago, Kristiina Lahde created her own toughest act to follow. Her solo exhibition, Ultra-Parallel, held at the Koffler Centre of the Arts in Toronto earlier in 2015, was a marvel. Lahde’s precise ordering of everyday measuring devices gave rise to novel geometric installations – the construction of which saw the artist often partnering with the force of gravity. At the center of that show, an outsized dodecahedron made from yardsticks suggested a bounded boundlessness, its transparent volume and immense calm forming a resolved paradox. Now, with From A Straight Line To A Curve, her fall exhibition at MKG127, the comparisons to Lahde’s previous successes are inevitable. For her part, though, she makes contrast the lead story – one she best tells with the breakthrough series, Ten-page spread.

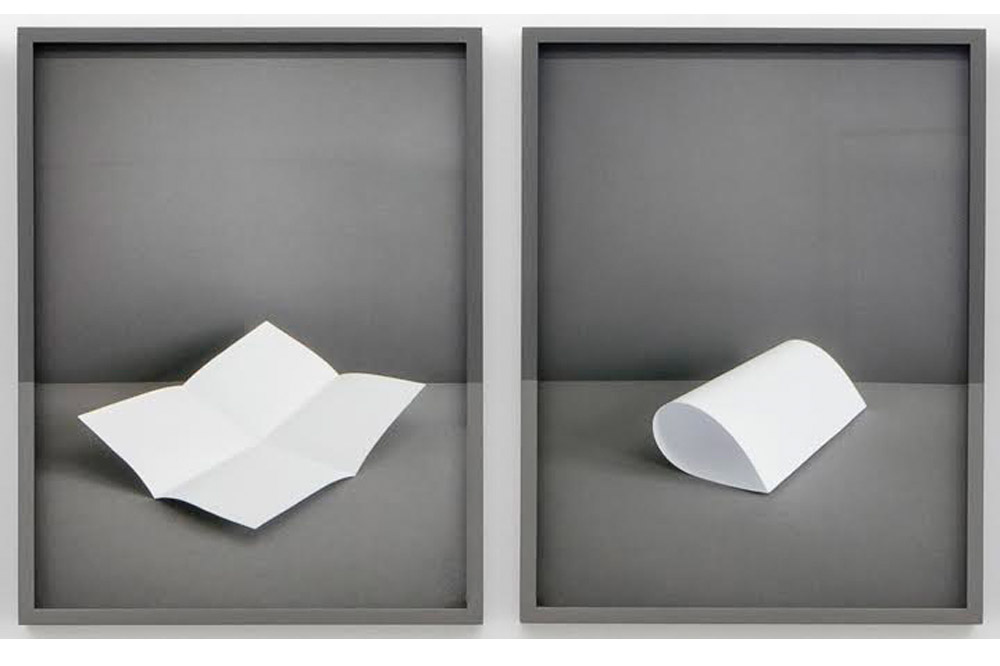

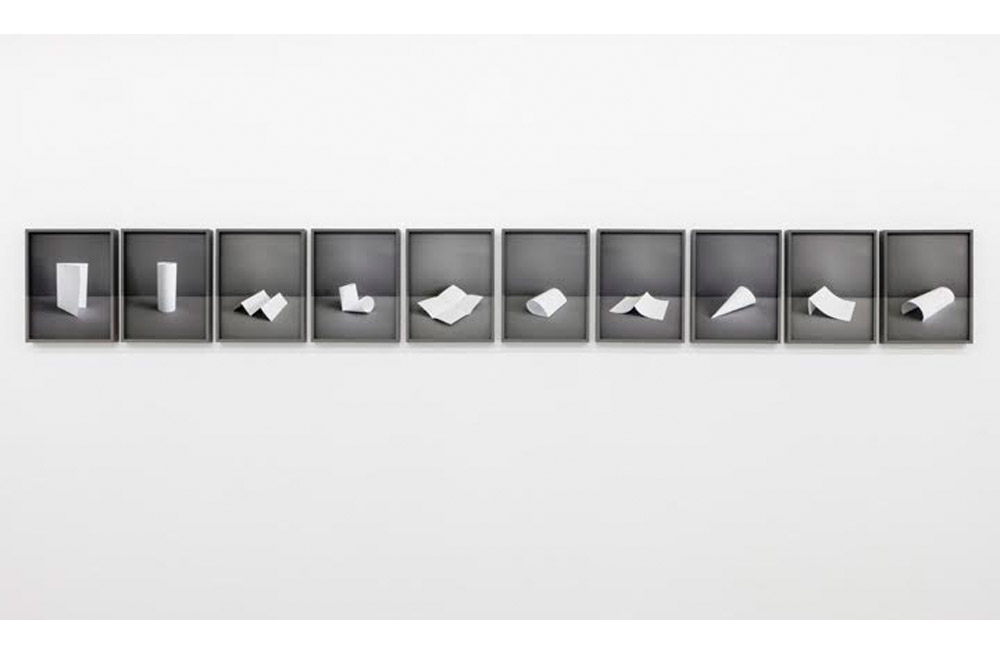

Unlike anything Lahde’s made before, Ten-page spread presents a line of photographs featuring ten white sculptural explorations produced from simply-folded paper, and set against a horizon-creased, two-toned grey background. The photographed paper is pulled into the physical realm by the works’ frames, which are exactly color-matched to the images’ back- and foregrounds. As a result, the volumetric white forms float as impossible objects, as optical illusions that hover in three-dimensional space, or structures that might be plucked from their shallow shadow boxes. The work cues a suspension of disbelief and employs, it seems, magic.

Ten-page spread marks a turn in the tale of Lahde’s recent practice. Shape and volume subsume line as her primary formal concern, and photography takes over from the readymade measure as medium. Similar to how Joan Fontcuberta recently described the Durational Photographs of Owen Kydd as trying to find the “degree zero” of film and photography, with Ten-page spread, Lahde blurs the boundary for where photography ends and sculpture begins.

This ten-part paper installation, a pivot-point for both this exhibition and her larger practice, stands in contrast to Lahde’s pencil drawings, and chalk, line, and ruler sculptures that assume the balance of the exhibition, and mark more direct formal and conceptual references to her earlier pieces. And while new works such as Chalk Lines or One Thousand Infinities might take up former techniques or subjects, they offer neither resolution nor a last word on the matter and their media, rather evidence of a methodical practice, a mode of understanding that can only be arrived at through making. Importantly, Lahde’s newest installations allow the artist to continue a conversation only just recently begun. Dealing in meta-disciplines such as mathematics and science and in big ideas like infinity and gravity, Lahde again compels them forward, allowing time and space for their abstract concepts to percolate into the real.

There is a richness of dialogue suggested by an artist working between two shows, and here it points to an important interplay between showing in commercial and public galleries, articulating something complementary between two essential institutions to an artist’s development. While Lahde has a long record of working with public galleries prior to the Koffler Centre exhibition – shows often allowing a yearlong runway for production and critical distance from commercial chatter – Ultra-Parallel allowed her to work to her largest scale yet.

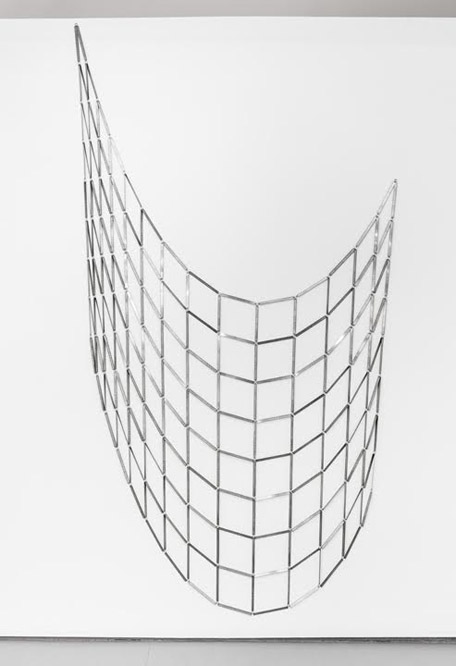

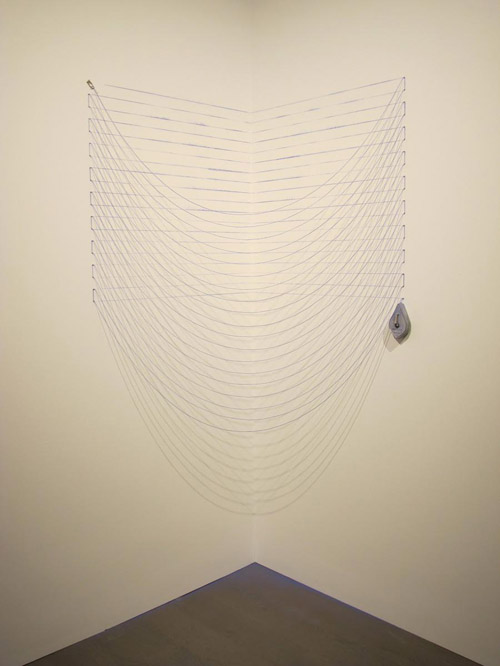

Lahde, then, seems to have relaxed, with nothing more to prove in her “homecoming” at MKG127. She is free to experiment with media and able to continue working through large concepts. She has the room to change, and the freedom to remain the same. Gallerist Michael Klein’s narrow space proves a productive constraint and is, in part, what allows for fabrication at the intimate scale of Ten-page spread (which was first produced facing the even tighter spatial restrictions of a print publication, Vector Journal). Space is an important variable for an artist such as Lahde, who employs a “slight-specificity” in practice, whereby installations or sculptures are neither totally dependent on, nor independent from site. A Series of Straight Edges stands out as a refined example, here, as one suspended iteration of a potentially infinite tessellation, as a restrained version of itself, shaped in part by the dimensions of the gallery wall. With its reminder to the audience of their relationship to a much larger whole, the human-scaled work carves out a type of contemplative space for her viewer. The same can be said for the exhibition in its entirety, in effect, as Lahde successfully converts rational building blocks into irrational imaginaries.

As a suggestion for how to follow one’s best act, From A Straight Line To A Curve proposes that the continuation of a story need not be a straight line, or a curve, but is perhaps best left to the ludic act of attempting to turn one into the other. This doesn’t imply that the artist’s path is facile or easy to emulate; for with the deceptively minimal style that is her own, Lahde makes even the impossible look easy.