Landscaping along the 87-mile stretch of highway from Shanghai to the ancient village of Wuzhen in southern China is a work in progress. On both sides of the four-lane road, slender saplings stand at attention every ten feet, each encircled by a tripod of supporting sticks and wire to ensure ramrod-straight growth. Clearly, the proverb “As the twig is bent, so grows the tree” holds sway in the People’s Republic of China.

Which is why the elaborate celebration around the inauguration of the Mu Xin Art Museum in November was so surprising. The new museum honors the art, life, and legacy of the scholar, painter, and writer Mu Xin (1927-2011), an artist whose path through life defied the straight party line.

The latest deviation in his meandering course is the artist’s emergence as a national treasure after nearly half a century as an enemy of the state purged from art history. In a recent interview, Alexandra Munroe, senior curator of Asian Art at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, called this about-face a sign of reform. Mu Xin, accused in 1971 of “anti-social” behavior and “counter-revolutionary tendencies,” is now seen, she said, “as a lost soul who maintained his integrity against all odds during the Cultural Revolution.” By erecting a museum to his memory, Mu Xin’s hometown of Wuzhen, she added, is “reclaiming Chinese humanism by bringing him back to light after being so abjectly eliminated from the intellectual history of China for fifty years.”

Fourteen years ago, Munroe co-curated the first-ever exhibition of Mu Xin’s art, an exhibition titled The Art of Mu Xin: Landscape Painting and Prison Notes. At the time, the 74-year-old artist was living in self-exile in New York and had no name recognition in the artworld. Members of the Chinese diaspora knew him only as a writer and teacher. However between 2001 and 2003, the show traveled throughout the US, receiving high praise.

That sudden rise from obscurity to acclaim marked another zigzag in Mu Xin’s career. Viewers were astonished by the originality of thirty-three landscape paintings, all created during the artist’s house arrest in China. Between 1977-79, risking his life, Mu Xin painted at night by light of a kerosene lamp, determined to maintain his identity as an artist after the Communist Party destroyed 500 paintings and twenty volumes of manuscripts. “By day I was a slave. By night I was a prince,” he later said. Toming Jun Liu, professor of English at California State University in Los Angeles, recalled his friend saying the secret paintings proved that “art has the capacity to resist any system that imprisons thinking and the body.”

Born to a wealthy family in the canal-town of Wuzhen, Mu Xin was part of the last generation to receive a classical education in the tradition of Chinese literati. What made his background exceptional was his access as a youth to the private library of a distant relative, the celebrated writer Mao Dun. There, Mu Xin devoured great works of literature from the ancient Greeks to Western modernist writers. He also studied contemporary Western art and paintings from the Italian High Renaissance.

After the Communist Revolution brought Mao Zedong to power in 1949, Mu Xin tried to keep a low, apolitical profile. However, like all members of the educated class during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), he was condemned. Imprisoned three times, he was first held in solitary confinement in a Red Guard pen (the basement of a former air raid shelter, flooded with filthy water), then sentenced to seven years’ hard labor in a factory, and two years of house arrest.

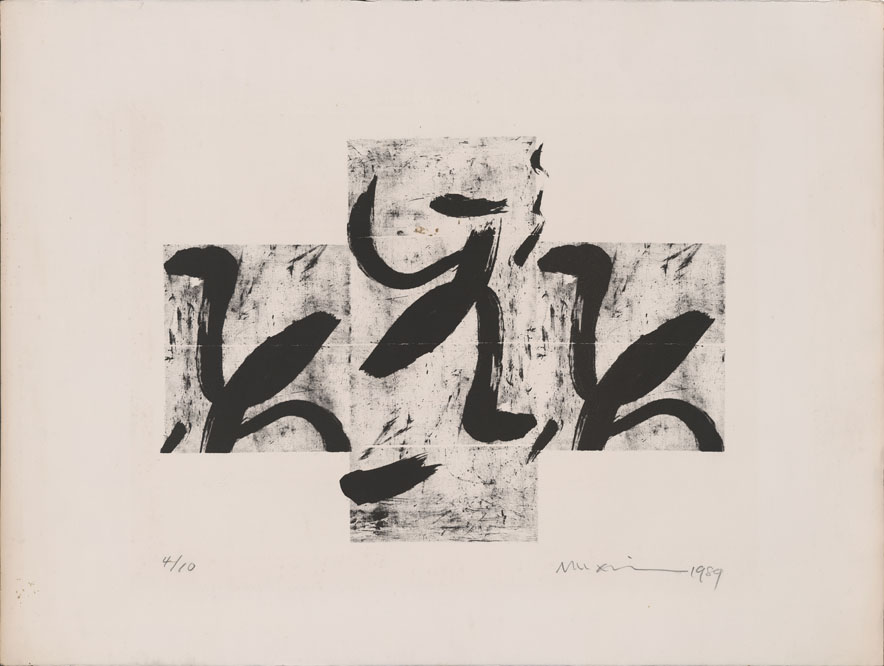

During Mu Xin’s imprisonment from 1971-72, at age 44, he demonstrated his integrity. Given paper and ink to confess his sins, Mu Xin proved so adept at homework that the guards gave him extra paper, ostensibly so he could outline his plans to become a better Communist. In secret, he diluted the blue ink and, despite three broken fingers, covered thirty-three double-sided pages with miniscule characters in a series of dialogues with great thinkers whose writings he’d internalized. “It was,” he said, “my way to stay alive.”

In a filmed interview shortly before his death, Mu Xin said that when he descended into Dante’s inferno, he went there with Shakespeare, Leonardo da Vinci, and other great artists. When released, Mu Xin smuggled his imaginary conversations with the likes of Aristotle, Rousseau, and Dostoevsky out of prison, on thin rice papers sewn into his clothes. Now known as The Prison Notes, they are enshrined in vitrines in the new museum, their delicate calligraphy faded and nearly indecipherable. “I was rejected by the absurd world at the time. So I built a more reasonable but magic world in which I sincerely lived, “ Mu Xin told his translator Toming in 2000.

Given China’s reluctance to acknowledge suffering caused by the Cultural Revolution (officially acknowledged as a mistake but still a taboo subject), this document’s visibility in a public museum is surprising. “It’s a remarkable testament to the perseverance of humanity and belief in the integrity of the soul against horrific odds,” according to Munroe. She speculated that the museum exists due to “an openness you could only find in the South,” adding, “You won’t find it in the official capital [Beijing] under the nose of the regime.”

What makes this museum unique is that it celebrates the work of a deceased artist who China hasn’t heard of. Even more unexpected, it spotlights an artist formerly considered, as he put it, “an intellectual with dangerous, decadent thoughts.” Mu Xin was seen as threatening in a society that values, above all, “social harmony” (the preferred term for collective conformity). “They can destroy my work,” Mu Xin said, “but they cannot destroy my talent.” Bringing this expunged chapter in social history back to life should be revelatory for a generation and newly vibrant middle class curious about the cultural past.

***

The museum in this thousand-year-old, well-preserved Ming village adds the zing of avant-garde art to its centuries-old houses that already bustle with masses of tourists keen for a taste of colorful tradition. The picturesque Wuzhen, undergoing a Renaissance, seeks to become a cultural destination like Kyoto, where big-city dwellers can get a taste of what life was like long ago.

The museum’s architects, Bing Lin and Hiroshi Okamoto of New York-based OLI Architecture, did not create a contextual structure. In a walk-through of the building, Okamoto told me that Mu Xin had encouraged him to take risks, saying, “Let’s not be afraid of making a statement.” The nearly 75,000 square-foot museum is unabashedly modernist, a series of rectangular boxes floating on Yuanbao Lake.

The museum’s concrete shell is sleek and elegant, while its interior appears spare to the point of austerity, and resolutely dark. The pervading dim light feels necessary because of the fragility of the manuscripts and works on paper, but it’s difficult to evaluate the paintings, especially miniature landscapes in 22-inch wide, horizontal strips, with painted slits only two inches high.

When Mu Xin saw plans for the museum shortly before his death in 2011, he summarized its esprit, saying, “Wind, water, and a bridge.” Okamoto said he incorporated the bridge metaphor into his design because Mu Xin’s writing, art, and character were a bridge between past and present.

***

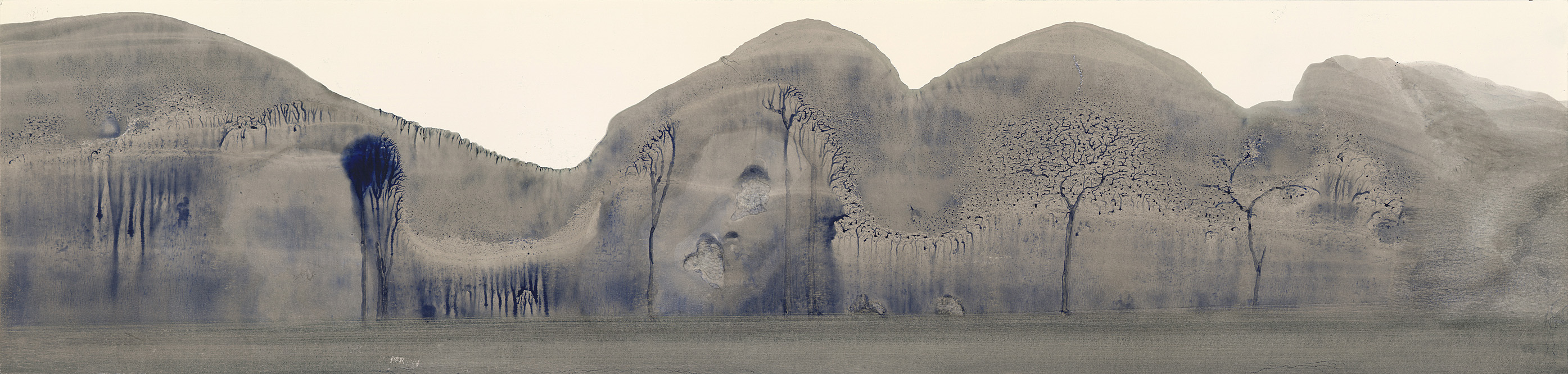

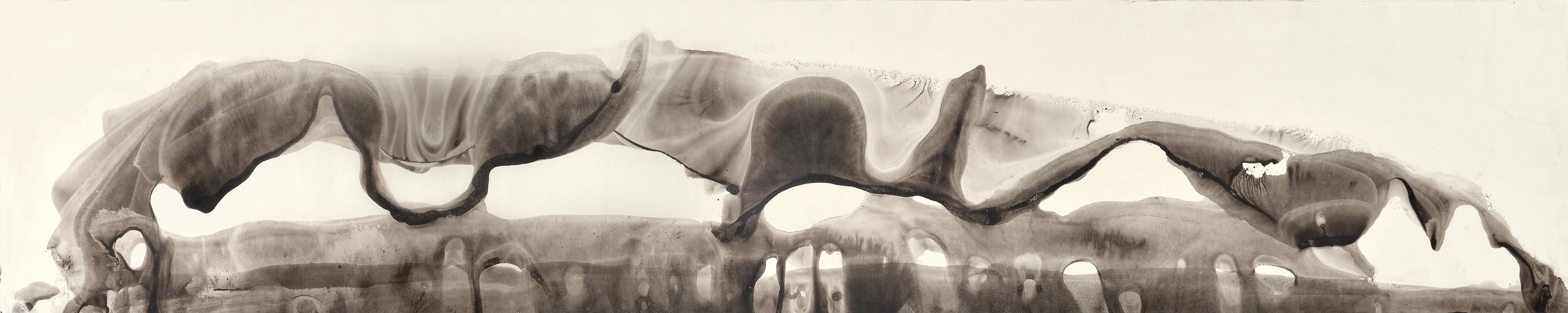

This hybrid nature of Mu Xin’s painting demonstrates his inventiveness – another deviation from a straight line of descent from the Chinese ink painting in which he was trained. The best series of his works – including his finest individual paintings – are the thirty-three landscape paintings created in 1977-79, now in the collection of the Yale University Art Museum. (Unfortunately, the Wuzhen museum displays none of these paintings. We can only hope that Yale will eventually offer loans.) The series at Yale, titled Tower within a Tower, are like no other Chinese landscape paintings. Mu Xin fluidly merged techniques from the classical ink-painting tradition with the misty, jagged backgrounds of Leonardo’s portraits and frottage and decalcomania techniques used by Surrealists like Max Ernst.

This innovative combination makes the work a singular contribution to Chinese art. Mu Xin apparently began by coating watercolor paper with a layer of thinned ink or gouache. Then he pressed another paper to the surface. Removing the top sheet produced amorphous, sponge-like forms reminiscent of geological strata or eroded craters on the moon. He then embellished these forms produced by chance with a brush, articulating them into landscape features.

What will be a revelation for new viewers are Mu Xin’s early, never-seen figurative paintings. Untitled (1970s), featuring the profile of a woman executed in colored ink, is elongated like a Modigliani portrait. A very early charcoal study of a figure’s thigh and buttocks has the muscularity of a Michelangelo sketch, showing Mu Xin’s skill with line. A blue cloud study is radiant, frothy like sea foam.

The founding director of the museum is esteemed artist Chen Danqing, Mu Xin’s student when the older artist lived in New York from 1982 to 2006. Eager to enlighten the public about the life and legacy of his friend, he said in an interview, “Mu Xin is the grandfather for young people born after 1980.” Mu Xin’s most ardent fans, Chen pointed out, are youth who first encountered his writing in 2006 when it was first published on the mainland after his return to Wuzhen.

Chen was blunt about why the Chinese public needs a bridge to pre-revolutionary times. Born in 1953, Chen himself received a party education. “I’m from the Mao’s kids’ generation. We all had the same language, the same thoughts, the same value system and habits,” he said, adding, “When I met Mu Xin [in the 1980s], it opened a window to see a different way, a lifestyle of the arts and philosophy.”

The museum aims to educate, not indoctrinate. “Young men today, as well as my generation, we never really knew what happened before,” Chen said. “Young people need to know what happened to our grandpa.”

Toming thinks this filling-in-the-blanks of the recent past is already happening, thanks to Mu Xin’s writings. Although the general public is still unaware of his visual art, which has never been on display until now, the new museum will reveal another facet of his legacy. Together, his artwork and writing will foster understanding of Mu Xin “as a free soul,” Toming said, “who even though his life was filled with adversity, kept his spirit free. He used the hardships and injustice he suffered as a motivation to defy the forces of coercion by continuing to create.”

Despite evincing a new spirit of openness, the museum has not escaped censorship. The last gallery, intended to show the Bible’s inspirational influence on Mu Xin, was empty when the museum opened, apparently failing to meet with officials’ approval.

It’s hard to change propaganda-infused minds, which were funneled into the mold of Communist ideology. Yet perhaps the newly public visibility of an artist outside the official system speaks to the reality that, as Toming said, “In this day and age, it’s difficult to maintain a rigid ideological line.” As young people become more skilled at evading the “firewall” that prevents access to social media, he added, “more diverse forces are determining what the culture should be.”

“Reveal the art; conceal the artist,” the camera-shy Mu Xin often said, quoting the writer Gustave Flaubert. Chen believes the statement was ironic, that Mu Xin hoped others would look for him. “He likes to hide; he likes to be found. He’s even hiding in this museum.” Those who seek him – a consummate, non-ideological individualist – will find “a message from the past and from the West, a message of humanism,” Chen said. He added Mu Xin’s conviction that, “if there is any help for the culture and the country, the only thing that can help is yourself. When my generation says we have to learn from tradition,” Chen explained, “on his side, tradition never left him – both Chinese and Western traditions, not defined as two separate cultures. It’s all part of him, inside of him.”

***

Even before multiculturalism was prevalent, Mu Xin believed in the connectedness of cultures. As he told Toming in a 1993 interview, “Culture is like the wind and the wind knows no boundary or center.” The Mu Xin Art Museum, an embodiment of “water, wind, and a bridge,” may foreshadow a freshening current of change blowing across China.

Yet, even there, tall stalks of newly-planted bamboo are constrained inside cages made of lathes to ensure they grow straight and true. They clack together like blond swords when rippled by the breeze. In Chinese art, bamboo is a symbol of character, indicating how a person may bend in the wind yet not break.

Bending and twisting as the path of Mu Xin’s life and work has been, straddling artistic and generational divides, it now stands revealed in the straight lines of a new museum’s pavilions. Perhaps a hint of China’s cultural evolution, this homage to an unbowed artist signifies a gust of humanism that defies boundaries of time and space.