This year’s spate of artworld controversies surrounding cultural appropriation and the ethics of representation suggests that we should sharpen our vocabulary, and find precise tools for understanding. Yet frequently these debates go hushed by a deadening abstraction: exhibitions drawing ire, such as the recent Whitney Biennial, have been defended in terms of “starting a conversation.” Conservative economists are fond of reminding us that it’s easier to spend resources that are not our own. With this in mind, we should ask ourselves: “just how much of another’s sorrow and grief is a conversation worth?” But in a deep, pit-of-the-stomach way, we also somehow understand that attention, not conversation, is the calculated end of controversy-baiting. Biennials, editors, festivals, and curators who deploy vague democratic ideals to justify valuably nauseating spectacle participate in a very contemporary form of cynicism.

Twitter accounts of celebrities and journalists often come with the disclaimer “RT does not equal endorsement.” The amorality underwriting this logic is routine, familiar: circulating media for attention, but disavowing responsibility for consequences or affiliation with its authors. As with many banal customs, the trend it signals is far from innocuous.

For one thing, our ease of image-diffusion has bred a wider forum, a more public stage, for things inherently repulsive and historically retrograde. The internet’s ready-to-hand soapbox has also brought an exhausting sense of entitlement among those most inclined to say prima facie abhorrent things: the sense that an expression, whatever its content, is pre-emptively justified at the level of an abstract right. But this is perhaps new in its scale alone.

We’ve never been able to utter so much while meaning so little. The sheer volume of texts and images available for one-click broadcasting is undoubtedly era-defining. And it’s increasingly noticeable that our ethical instincts haven’t yet caught up to our capabilities on this front. Walter Benjamin warned us: the evolution of our tools for reproducing images outpaces our understanding of how those technologies change us.

So what does this ethical lag have to do with the sharp-edged conversations that so many institutions (the Whitney Museum and the Walker Art Center, to name a high-profile pair; also the journalists supporting the recent “Cultural Appropriation Prize” proposed in a Canadian journal) are apparently eager to start? We’ve grown accustomed to a certain skepticism that simply because someone says, shares, or gives a forum for something, doesn’t mean that they believe in it. Increasingly, representation uncouples from meaning in the popular consciousness. It’s a straight shot from this growing schism between sharing and defending, to a dangerous cynicism, willing to forge a profitable opportunism in appropriating and trading on the signs and symbols of oppression and resistance. Cynicism being empathy’s natural enemy, this trend can only hurt our ability to see and understand others. Surely these are necessary coordinates for any conversation worth having.

And surely our moral intuitions are relevant. Even from a subject position of one who’s able to reflect on appropriation without an immediate sting of personal pain, there’s an ache that attends the victory of cynical unaccountability – especially when it masquerades as a desire for real dialogue.

To cast controversy-baiting in terms of free speech, in terms of entitlement and censorship, is to fundamentally and willfully miss the important ethical point. When we’re this able – both technologically and in terms of our rights – to say or to show anything we might imagine, the decisions that ensue aren’t trivial. It isn’t that the democratic ideal of free expression isn’t worth defending (as the contrary straw-man holds). Rather, the point is that making the choice to cast responses to harmful representation in terms of value-neutral “conversations” ignores the critical role of the forum in prioritizing, amplifying, or silencing certain voices.

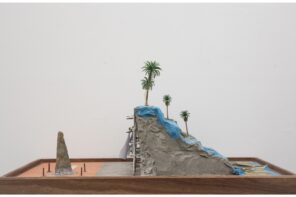

Love, said Jacques Lacan, is giving something you don’t have to someone who doesn’t want it. When documenta14 lovingly gifted its “learning” upon a manifestly subaltern, economically humiliated Athens, it was, of course, free to do so – a fact arguably worth celebrating, especially given the history of fascism in the city of Kassel. But this celebration is not, itself, a conversation. In one of the most iconic works of this year’s exhibition, Argentine artist Marta Minujín, in collaboration with “the documenta14 team,” gathered thousands of banned books from various countries and sculpted them into the shape of the Athenian Parthenon. It’s difficult not to read in the description of Kassel’s most prominently displayed work a broad, reaching justification of something large and conspicuously Greek: “The installation The Parthenon of Books will be presented in Kassel as a replica of the temple on the Acropolis in Athens, which symbolizes the aesthetic and political ideals of the world’s first democracy.”

Minujín initially organized a version of the work in 1983 to protest her home country’s crackdown on dissident literature. It has been ported here, into the German context, under a pretext of marking the site of Nazi book burnings, as well as memorializing an important library destroyed by Allied bombardment during WWII. But why now? The work was exceptionally timely in its first iteration. Today, it stands before a necessary discussion about the appropriation of Greece’s culture by its economic wardens in Europe – and sublimates this to a rather bland point about the importance of free speech.

In this, documenta14’s Parthenon of banned books is a perfect symbol for the contemporary ethical condition that will likely continue to revel in queasy controversy. Here’s the most superficial image of Greekness – the one from all the postcards – in homage to an untrammeled right to European speaking-for, and the moral agnosticism of the winners of history. Within art’s increasingly spectacle-dependent economy, sharing is no longer caring.

2 Comments