Over five years, from 1992 to 1997, Tom Friedman produced 1000 Hours of Staring, a work of pure intention and immaculate material. A blank sheet, Friedman listed its media “stare on paper.” The title says the rest, testimony to an artistic action that defies any conventional notion of performance or documentation. Its transition from studio to gallery, framed behind glass and now in the collection of MoMA, has apparently made it impervious to all subsequent stares.

In 2009, Ken Nicol produced The Button I Pressed One Million Times, a fist-sized, cubic steel box housing an analogue counter that responded to a red plastic video-game tab. Its title similarly tells a tale of compulsive action and its indexical numeration. Nicol, too, knew exactly when to stop; the digital counter is deactivated at 1,000,000. On his website he explains, with some self-deprecation, “Several works I’ve done are about understanding and appreciating numbers. [This] is a ridiculous but important exercise to better understand one million.” At the time, Nicol supported himself by fabricating artworks for others, typically neo-conceptualists who sought his exceptional manual and mechanical skills to bring their ideas to almost perfect form. So, while seeming to share much in the way of self-reliance with 1000 Hours of Staring, Nicol’s work entails a complicating quotient of needfulness – and not only the needs of others! Nicol fulfills his acute preoccupations with reflex, habit, routine, control, measurement, and verification. His practice hews closely to those of twitchy, tactile, first-generation minimalists such as Carl Andre or Alan Saret – studio-bound to the point of obsession.

Nicol’s art provokes trepidation. It stands on the brink of a potentially hazardous slide into someone else’s solipsism, governed by systems, numbers, and rules all-too temptingly assimilated and calculable. Nicol’s finely-measured objects, minutely-inscribed lists, and monotonously-transcribed ruminations can lure one into confining mental lairs that are difficult to escape from. Consequently, his art has always performed well in cramped and busy settings, such as art fairs, where the concentric experience seemingly offers secret respite; his work performs less successfully, however, in group exhibitions, where it often yields exactly the sum (or product or dividend) of its parts.

Nicol’s first solo exhibition in the capacious setting of Olga Korper Gallery, therefore, presents an anticipated test. Instead of the usual abundant array of gimcrack ingenuity, as shows at his previous Toronto gallery (MKG127) comprised, …and it is ending one minute at a time. brings together a remarkably cohesive set of endeavors. They superbly utilize the extent of the available gallery space, simultaneously opulent and efficient.

These qualities combine in matrices of crystalline, sequential beauty and serial labor. The major project, this is your life… (2015), is a monument to detail and tedium. Nicol executed 55 30-x-20-inch drawings on an extra-wide Underwood SX 150 typewriter that can deliver up to 220 keystrokes per line. He devised a 55-character sentence that can be repeated four times in a row – this is your life and it’s ending one minute at a time. In each drawing, the sentence repeats 480 times; the word minute occurs as frequently as in an eight-hour work day. From a short distance, it becomes impossible to apprehend the linguistic content. The initial drawing reconfigures into a barcode-like pattern of vertical columns of words, letters, and spaces down the paper. For each successive drawing, the line length is reduced by one character (i.e., 220 to 219, 218, etc.) and the sentences creep incrementally further into the next line. Therefore the grid shifts ever so slightly. Over the entire series, every possible permutation has been produced. Do you need to know all this to appreciate it? Maybe not. It’s maddening. And yet the impassive intricacy of the premise supports the larger endeavor.

Nicol’s faith in analogue mechanics and mechanisms, such as typewriters and wind-up clocks, serves as a reminder that these devices are themselves analogies for language and time. Time is a reductive concept derived from terrestrial, solar, and universal forces that humanity still scarcely comprehends. If the great Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges mocked the limitations of art in his very short story “On Exactitude in Science,” then Nicol gently pokes technology as an inexactitude of art; the harder it strives, the more apparent the fallacies of scientific determinism begin to seem. Language drawing of this sort, reductio ad absurdum, offers a near counterpart to New York poet Kenneth Goldsmith’s practice of uncreative writing.

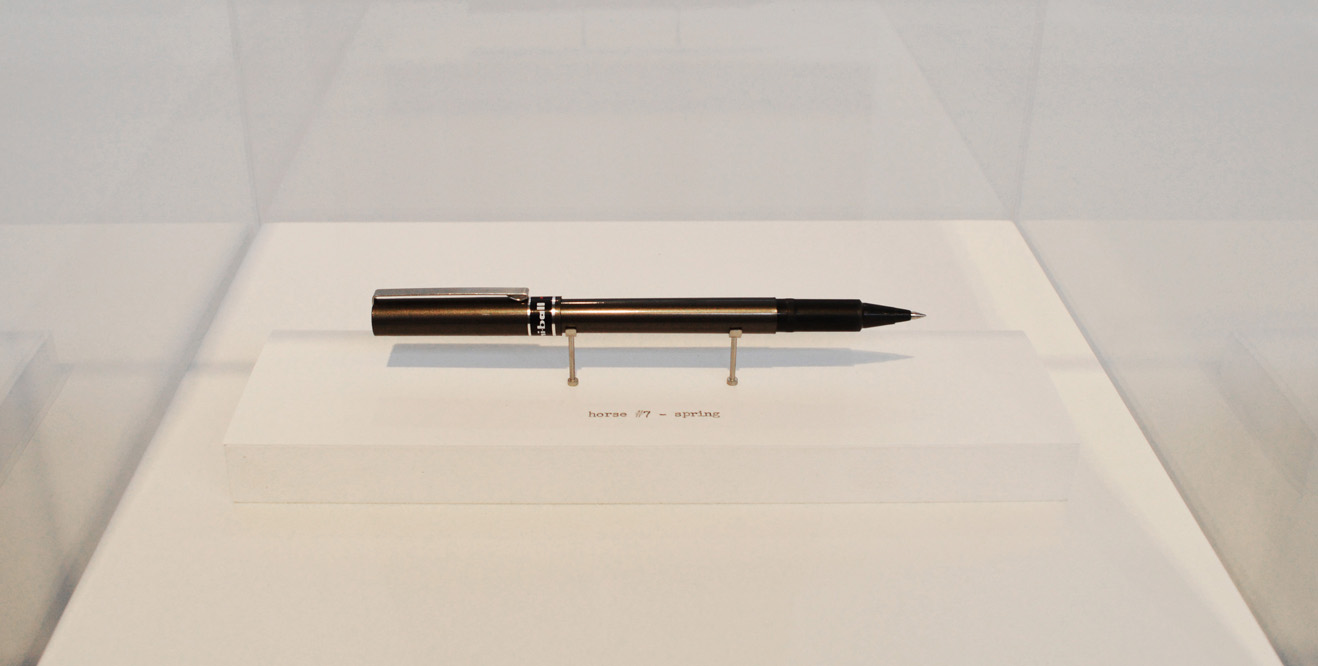

The major opus generates two subsidiaries. In …and it’s ending one minute at a time., Nicol retypes the same sentences, however this time with the ribbon removed. The first several hundred keystrokes deposit accumulated ink, but gradually the metal keys clean themselves and leave only their embossments on the sheets. Nicol uses Stonehenge paper so that even those pieces that seem to refer to the standard office letter and ledger formats consist of fibrous, acid-free, artist’s-grade material. this is your life…corrections acknowledges and collects mistakes that Nicol made on the big series, plenty but far fewer than you’d think. Over 55 drawings, there are 1,452,000 character spaces. (The Button I Pressed One Million Times proved to be a relevant boot-camp for this campaign.) Each of five correction film tabs, surgically stretched between a pair of fine stainless-steel brackets, is displayed in its own miniature trophy case.

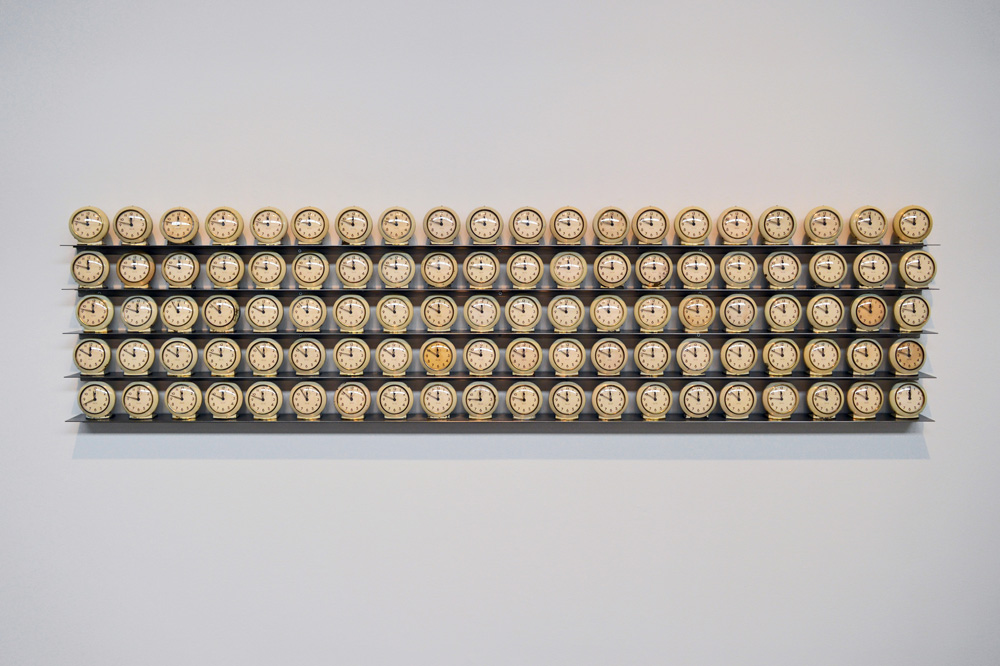

Other major works in the exhibition, while of high standard, do not make quite the same impact. For instance, one hundred of the same clock, a squadron of vintage Baby Ben alarm clocks in parade formation on five stacked shelves, “whisper[ing] away the lost seconds of the day” (as the gallery media release so eloquently and suggestively puts it), does little more than scale up, structure, and cap the artist’s acquisitive compulsion. The unseen and unstated upshot is that this installation requires Nicol to make frequent, almost daily visits to rewind and reset the clocks. Should one happenstance upon him in the gallery during this ritual, it would be noted that he does so with an ease and pleasure that belie his obsessive, pathological stereotype.

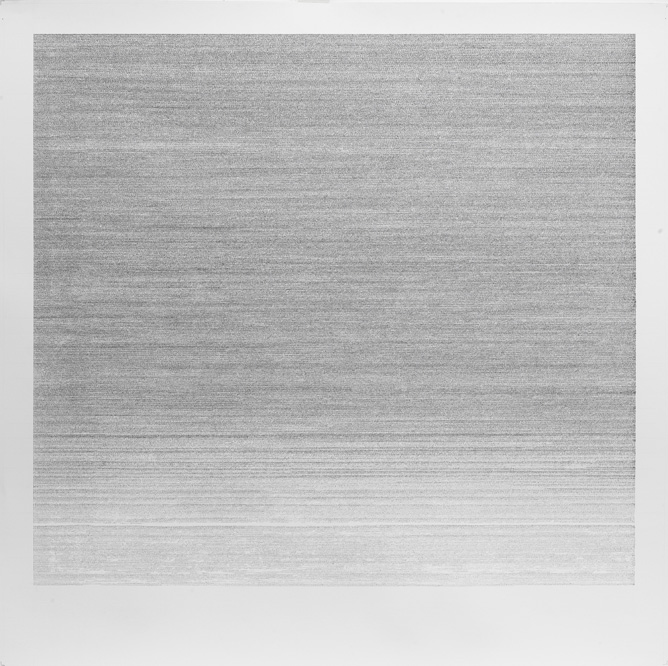

Significantly, a series of four flogging a dead horse drawings, numbers 6 through 9, were executed respectively in winter, spring, summer, and fall of 2012, indicating that Nicol had designs on expanding his scope well before he found an appropriate outlet. In this series, he hand-marked tiny tally strokes, row by row, with a fine-point Uniball pen until the ink ran out, then continued, sapping its last reserves, and still went on marking with the dry tip until the grid was completely filled. The constraint of each work was that it had to be done within the days of that season. Success was by no means assured. He attempted this before 2012 and failed.

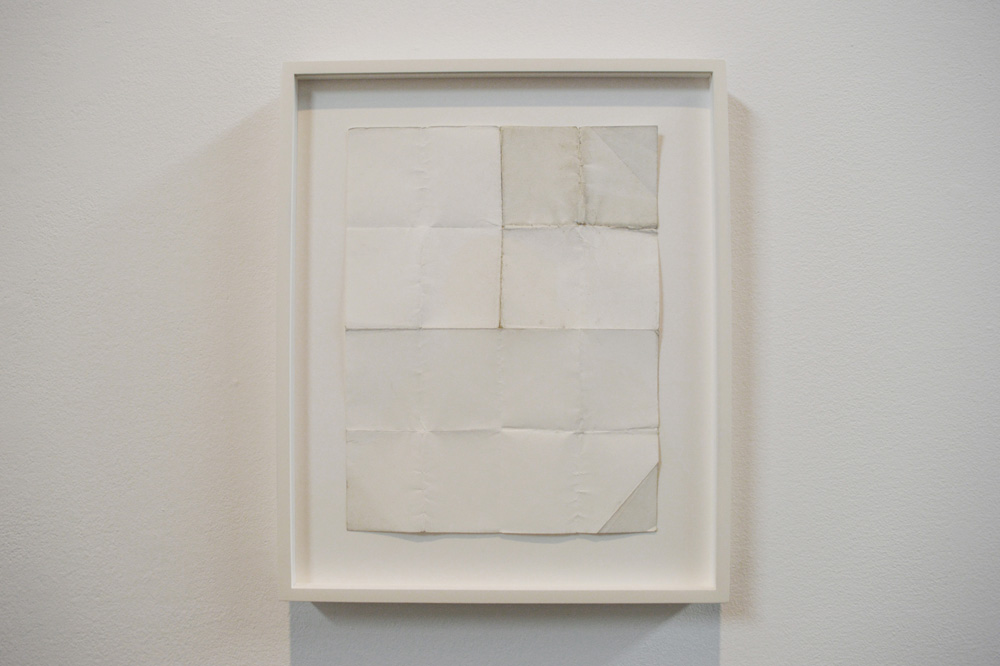

One might call Nicol an exquisite reactionary, troublemaking the extremes of control and chance. ninety three and one half day letter, the smallest work in the exhibition, closes this loop. An 8 ½-x-11-inch sheet of Stonehenge (that is to say, hand-trimmed, not taken from an office ream), Nicol folded the paper in half four times and carried it in his back pants pocket for a duration, in days, that are the product of its dimensions (8 ½ x 11 = 93 ½). Unfolded and framed, the sheet has acquired one incidental diagonal crease, reflected in the upper- and lower-right corners. It has become grubby, somewhat burnished, but otherwise blank. Like 1000 Hours of Staring, ninety three and one half day letter seems to be a work of utter intention. However, its intention is unattended. To Friedman’s heads, Nicol blessedly comes up tails. Free your mind … and your ass will follow.

What a clear and well-written piece. Loved the show, too.