It must also be said that the painter is not hysterical, in the sense of a negation in negative theology. Abjection becomes splendor, the horror of life becomes a very pure and very intense life.

– Gilles Deleuze

Stinking, wretched, naked but for socks, smeared with his own thick feculence, the man is arrested by police and order is restored. So ends performance artist Günter Brus’s infamous Kunst und Revolution (Art and Revolution) in 1968. For it, Brus urinates in a glass, covers his body with excrement, masturbates while singing the Austrian national anthem, and finally drinks his own urine, vomiting. Along with co-organizers Otto Muehl and Oswald Wiener, Brus was sentenced to a six-month jail term for obscenity, though he later escaped with his wife and child to West Berlin. Art and Revolution is, however, only indirectly the focus of the Brus retrospective Unrest After the Storm at the Belvedere 21 contemporary art museum in Vienna.

Known locally as the “21er Haus,” the institution is a recent addition to the Belvedere museum, housed in a generically modernist cuboid building just beyond the colossal palace garden, between a busy inner-ring road and the utilitarian sheen of a new urban living and shopping complex. The older Belvedere’s collection boasts an overview of the historical development of Austrian art, including The Kiss (1908/9) by Gustav Klimt, but the younger 21er Haus focuses on contemporary Austrian art and “its embedding in an international context.”

Unrest After the Storm reminds us that Brus’s transgressive actions of the 1960s – violent, destructive, non-commodifiable performances – were once vital interrogations of Austria’s Nazi past by the next generation. They contain some of the eeriest imagery in contemporary art history, including real and simulated self-mutilation, and set pieces in which the artist covers himself in paint and thrashes against white surfaces or pieces of cloth. The safe confines of this exhibition, however, embody the diminishing power of transgressive art in a conservative national culture.

This is profoundly ironic. The actionists once challenged Austria’s narrow provincialism while remaining isolated from the wider international avant-garde. Now they represent one of its proudest achievements, cementing the country’s place in the global art market and museum culture. 21er Haus’s year-long “Spirit of ‘68” theme, meanwhile, lends an air of acceptability to these ghastly spectacles, as if they now sit happily alongside the Mozart or Jugendstil kitsch preferred by the tourist board.

The year 1968, in the quiet Alpine republic, is often called Die zahme Revolution (“the tame revolution”), when compared to the anti-authoritarian events in Paris, Prague, West Germany, and the United States. Art and Revolution, for which Brus was charged with “violating public morality” and “degrading Austrian state symbols,” was perhaps Austria’s best-known contribution to that year’s events. It was not unprecedented, though. Brus’s 1960s actions openly sought public disapproval. This reached its height with Art and Revolution, which dredges up the sordid secret beneath post-war Austrian politics: the deceit of the Opferdoktrin (“victim theory”).

According to this potent national myth, many Austrians portrayed themselves as the unwilling first victims of Nazi aggression despite abundant evidence of the contrary: the jubilant saluting crowds greeting Hitler’s procession into Vienna, the many photographs of Jews publicly humiliated to the grins and taunts of their tormentors. Not unlike Berlin, Vienna (and the rest of Austria) was split up into different administrative zones occupied by American, British, French, and Soviet troops from 1945-55. After regaining sovereignty, a grand coalition of conservatives and social democrats in the Austrian parliament rehabilitated former Nazis. They rejected the claims for the restitution of stolen property by the few Jews who inconveniently returned to the country, casting these real victims as self-aggrandizers, disloyal to the Second Republic. By “degrading” Austrian state symbols, Brus was merely demonstrating how these images were already compromised, with no claim to moral authority.

Art and Revolution is not just a visual stunt, but a transgression in the way Georges Bataille described it: a temporary form of rationalized violence. For him, transgressive acts make collective life meaningful, showing the limits of public acceptability by breaking taboos without undermining the fabric of society. Similarly, Art and Revolution draws attention to the real meaning and otherwise unquestioned implications of “victim theory” without changing anything (as if it really could). Though Brus and his collaborators were punished by the state, Austria’s relation to its own past remained unruffled. Kurt Waldheim, an SA officer later accused of war crimes, became the country’s president from 1986-92, and The Republic of Austria only admitted its “responsibility” for its past in 1991.

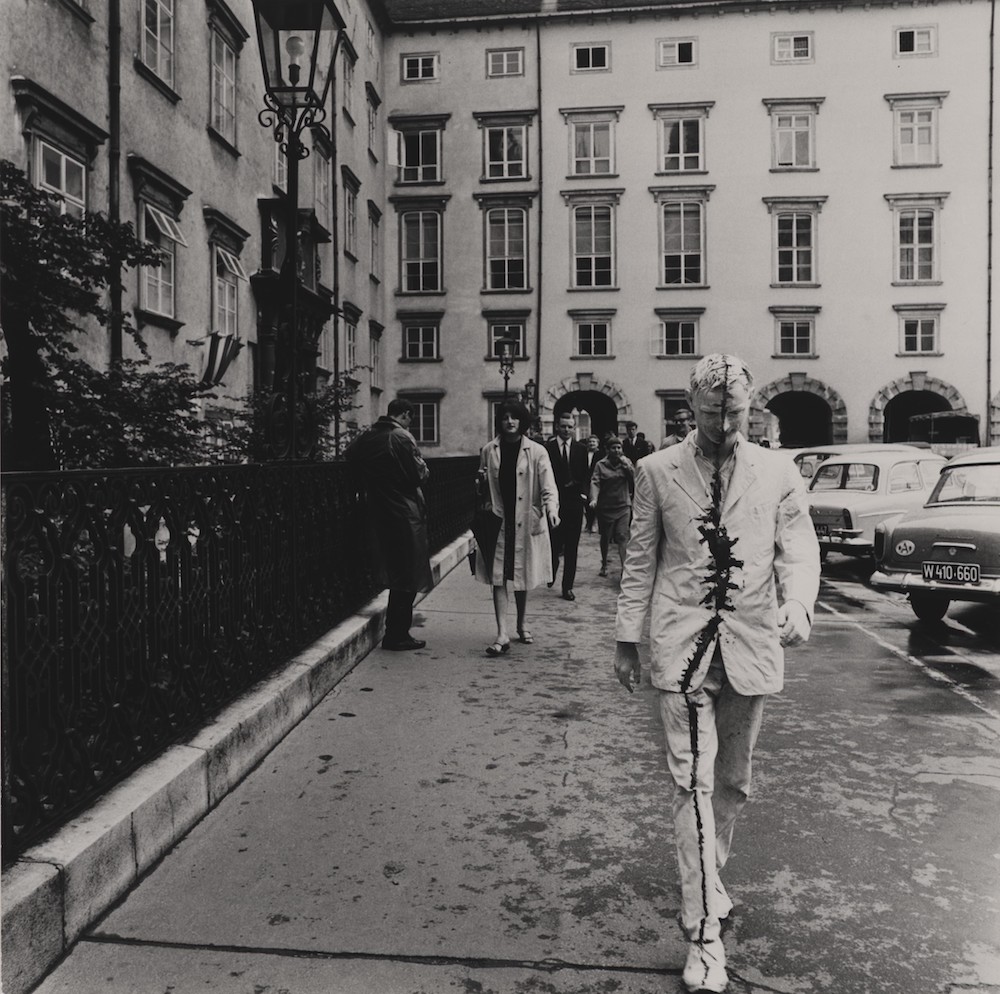

Brus serves up this bleak self-reflection with a typically bitter Viennese sense of humor that sometimes masks the political implications of his work. The first six images of Wiener Spaziergang (Viennese Stroll, 1965), for example, are ghoulishly amusing. Painted white, with a jagged slash painted through the middle of his body, Brus takes a walk through Vienna’s historical center. He is documented walking past smart storefronts and tourist hotspots, is gawped at by fussy locals, and finally booked and firmly rebuked by a stern-faced police officer. The later images are much more troubling. Lying prone, corpselike, on a table surrounded by scalpels, Brus claws at his sludge-covered face and appears to stab himself in the thigh. He eventually falls and drags himself, agonized, across the floor.

Curator Harald Krejci admits that images like these cannot maintain their transgressive force now that “nudity has lost some of its power to shock.” This is unconvincing. Nudity is less the issue than how Brus’s performing body, clothed or not, still looks horrifyingly anonymous, even inhuman, like wounded ghosts stalking a military hospital, or the walking dead at Mauthausen. In his catalogue essay, however, Krejci points to the subtlety with which Brus transgressed the limits of painting. Given the wide focus of this retrospective, this provides us with a way of thinking about the importance of the other works while at the same time unexpectedly demonstrating why Art and Revolution represents the apex and exhaustion of Brus’s transgressive energies. Krejci writes that, following a 1960 encounter with Joan Merritt in Mallorca, Brus “internalized abstract art,” opening and breaking through the picture space, forcing it into a new relationship with his own body, which replaced traditional materials. “The problem,” Krejci says, “was still the canvas: or, rather: painting and the artist’s relationship to it.”

The intuitive energy of Brus’s early paintings, like Ohne Titel (1960), and Ohne Titel (Informel, 1961) represent his aggressive challenge to painterly conventions – he mixed paint with his own bodily fluids – while still producing pictures. Within a few years, Brus pushed this further by replacing the canvas with either a sheet or his own flesh. Like the Minimalists working around the same time, Brus emphasized documentation of specifically-timed processes over making works. Unlike them, however, he returns the figure to art, but only by using his body – gnarled hand muscles, prostrated torso, savaged skin – without either abandoning or relying on the formal conventions of modern painting.

Shifting the focus from politics to painting cannot escape the fact that Brus’s actions – especially Art and Revolution – are and should remain our chief source of interest. Unrest After the Storm places these in the context of his abstract paintings, but also his works on paper: image-texts, poetry, opera, and theater-inspired stage and costume designs. This exhibition displays only a few documents from Art and Revolution: just enough to show that this performance, and not the later works, represents the substance of the “spirit of ‘68” in Austria. Actionism is exhibited too frequently in Vienna but, for an international audience largely unaware of Austria’s relation to its own past, Brus’s transgressions must be underscored to make sense of the nationally-specific character of this spirit.

Today we are living through the delayed revenge of conservative elements in Austrian society. In December 2017, Austria elected a new government – a coalition of the conservative People’s Party and far-right Freedom Party (formed in the 1950s by unrepentant ex-Nazis) with plans for big changes. One of their first moves was to issue a 182-page five-year cultural plan, statingthat “engagement with [Austrian] common cultural heritage […] contributes significantly to Austria’s sense of identity.” While pointing out that obvious censorship will be unlikely, Vienna-based American writer Kimberly Bradley warns instead of the “vilification of provocative aesthetics in favour of conservative ones.” Unrest After the Storm offers no explicit resistance to this political climate; on the contrary, it illustrates how Brus is now an elder statesman, representing Austria’s place in a global culture network. Brus’s provocative aesthetics have certainly not become conservative, but there is the risk that the art-industrial complex will work on behalf of the conservatives, making Brus epitomize the very heritage and identity he once scorned.

10 Comments