Yellow’s a strange cornstarch slurry of a word, one that quickly gets thick on the tongue and loses all meaning. Its symbolism oscillates wildly, from the champagne glamor of Gatsby’s “yellow cocktail parties” to the seediness of yellow journalism, or a cowardly yellow streak. Interior decorators and vegetable oil marketers alike praise its connotations of sunny cheeriness, and corn, canola, safflower, or sunflower-induced healthiness. It’s in this last guise that it becomes ubiquitous in Ghana, in the gallon containers used to import cooking oil from Europe before being recycled to hold petrol and water. Sometimes they might be blue or white, but shades of yellow are most common: cadmium to bismuth and everything in between.

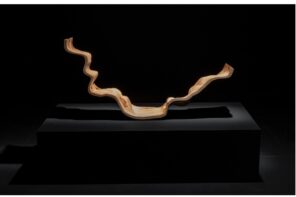

Imported all the way from the former Gold Coast to the erstwhile Pirate coast, these jerrycans now abound in a Dubai gallery. More precisely, they form the basis of Accra-based Gallery 1957’s temporary takeover of Lawrie Shabibi’s space, which features Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey in his first Middle Eastern solo show. They’re cut up into squares or rectangles and assembled, using wire, into a number of very large, very yellow tapestries. In some squares the original branding and barcodes remain visible, as fragments of tag-lined promises float by. A mark of purity; for perfect cooking; 100% pure vegetable oil. These wall-hung sculptures are marked up with oil paint and, taken as a whole, suggest a particular kind of Ghanaian kente. Clottey calls this technique “Afrogallonism,” which he defines as a concept designed to “explore the relationship between the prevalence of the yellow oil gallons in regards to consumption and necessity in the life of the modern Africa.” Between repurposing the discards of the country’s growing consumerism and the geometric, wire-linked forms of his paintings Clottey invites comparisons to El Anatsui – but is that just because I know so little about Ghanaian art?

Now say “takeover” enough times, and it quickly loses meaning, too. The “initiative” (as the press release calls it) is titled Gallery Takeover by Gallery 1957 from Accra, Ghana. Clottey feels like something of an afterthought here: the bowl of lemons, angled on the kitchen counter for the open house. Even framed as a move that “emulates current trends,” the concept of this kind of south-south solidaristic move is immediately seductive, as are the plans for the initiative to grow in future years, in the manner of CONDO London and New York. Promotional materials starburst the cultural exchange with all the palm-extended subtlety of a model on The Price is Right. The Ghanaian gallerist and artist would be available to speak about the work, the takeover, and the growing art scene in West Africa. Local audiences, meanwhile, would be treated to something new, exciting, never seen before, a sentiment echoed by an American curator who was visiting the space at the same time as me: “at least it’s something fresh for here.”

Dubai’s multiracialism resembles neither a mosaic nor – worse – a melting pot that sublimates difference into a national mandate. Rather, it’s something far more aggressive, perhaps dialectical; links between discrete communities can be as tenuously reinforcing as those between Clottey’s squares. How can overt cosmopolitanism allow so few to be part of the same polity? And it’s difficult to ignore the fetishistic overtones already prevalent in the UAE art scene’s strategy of becoming a warehouse not just for trade and tourism but culture too. Consider Art Dubai’s positioning itself as a fair of discovery, particularly in its former “Marker” section, which focused, each year, on an underrepresented art market. (Featured regions included the Philippines, Central Asia, West Africa, and Southeast Asia, among others.) Occasionally the encounters thrilled, despite an oily colonialist mouthfeel that lingered afterwards, hard to displace.

In the Ghana of the 2000s, the jerrycans became synonymous with water shortages, resulting in their being informally dubbed “Kufuor gallons,” after then-president John Kufuor. A decade later, China now supplies much of the cooking oil as well as waste management technology. But the water crisis continues and the supply of containers outpaces the availability of water with which to fill them. Along with other plastic detritus, they accumulate on streets and on beaches, as litter and as hazardous waste that threatens wildlife and clogs sanitation infrastructure with serious repercussions for public health. It’s a global problem, but one acutely felt in Ghana, where recycling rates are low and the best efforts of beleaguered waste-management companies don’t barricade enough of the encroaching jaundiced tide.

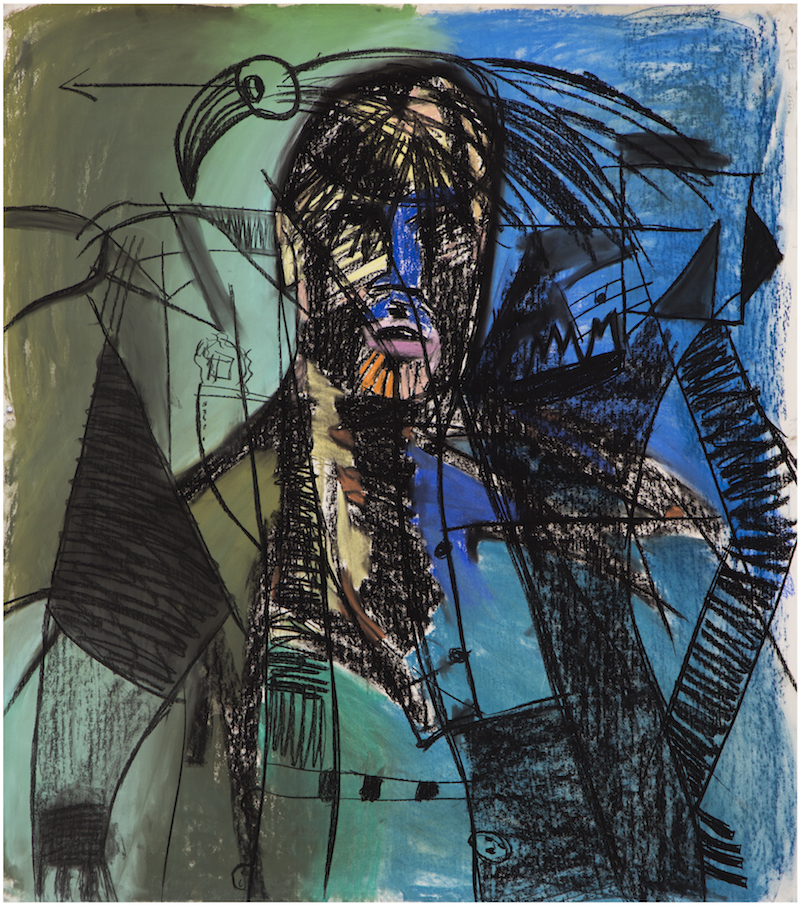

The thing about jaundice is that it’s markedly visible. It indicates something’s wrong, maybe really wrong, but doesn’t immediately offer much information as to the underlying causes. We might see a yellowing of the eyes or a tingeing of the skin, as in the nine pastel and charcoal drawings on paper that, along with a short video, round out Clottey’s show. The sketchy drawings depart from the monochrome palette of his previous charcoals and largely depict voluptuous nudes. Women’s heads are either cut off or radically shrunken in a manner that suggests amputation; in one drawing, three sets of limbs entangle and overlap as if caught mid-ménage. The few men meanwhile appear as angular, elongated forms with planar, wood carving-like heads, which recur in the statuesque masks of the video. They are powerfully built, with insistent traps, defined pecs, and abs like fresh sutures. In their disjointed forms they might read as proto-Cubist, except that that movement itself turned on repurposing African sculptural forms. The titles hint at humor: the aforementioned trio of Volunteers Abroad (all works 2017) to skewer the psychosexual romp of the NGO-industrial complex, while in In Today’s Economy, a figure slumps with a half-empty bottle.

Some of the drawings include arrows that seem to go nowhere, foregrounding a theme of constrained mobility that continues in the video The Displaced (a secondary title of “the initiative”). The beach is so carpeted in trash that you wonder if all the discarded plastic will break down over time and eventually replace shells and quartz as a new, more toxic kind of sand. This flotsam laps sickeningly into the water while shots of people draped in blue netting invoke asphyxiated marine life. These very still scenes, in which only the nets or people’s braids are ruffled gently by the sea breeze, are interspersed with others of movement – people snaking down to the beach, feet marching, a boat cresting the waves – suggestive of a perpetual, stop-and-start arrested motion.

And here, too, are the ubiquitous yellow containers: sometimes whole and sometimes cut and drilled and stitched into Clottey’s diamonded tapestries (rewardingly mirrored in one woman’s checkered top), or fashioned into masks mounted on sticks on the beach where the containers’ openings become gaping mouths. A procession down to the water follows a flurry of preparation; men get onto a boat as women wave them goodbye. The masked army waits on the empty beach, as if watching for their return. Almost as soon as the boat leaves, we see it arrive again to dancing, and drinking. There’s an exchange of sodden clothes for natty dried ones and pounded meat – or perhaps a particularly bloody fish – being cleaved up for the evening meal.

The video is mounted on a screen at the end of a short passageway that works to induce a kind of nervous claustrophobia, even when the gallery is empty. It’s all terribly Dubai. In the opening shots, a disembodied hand sketches a crude map labelled with ROAD and SEA in the dim light of makeshift oil lamps: an allusion to the trade and migration summarily invoked by the wall text, perhaps? In practice though the video suggests a far more ordinary snapshot of a coastal Ghanaian community. But its tenderness never becomes mawkish. They aren’t dancing for you.