To cast back and select my favorite art this year requires a mnemonic leap of faith. I’d hope the ‘best’ exhibitions, pieces, and events leap to mind immediately on the grounds of their quality or, at least, impact. In waiting for those reminders, though, my realization was that the majority of the work to which I returned, physically and psychically, was made by women. Chalk this up to coincidence or a personal proclivity, but in putting the pieces together I noticed that my favorite works engaged with the institution in ways agonistic, cooperative, or assertively ambivalent. Some exhibitions found themselves sizing up their institutional frameworks, while others were embattled. Individual works seemed to revive or enhance weaker group presentations. But all spoke to questions of feminism and gender in their myriad forms and guises.

Granted, the appearance of the artists, curators, and writers, here, is a matter of (my) good timing, but in the spirit of an annual resolution, here’s hoping some themes, tactics, and toughness – feminist or otherwise – get picked up and amplified in the coming calendar year.

“Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video” at the Guggenheim

Carrie Mae Weems’s retrospective at the New York Guggenheim was everything a single-artist exhibition should be: historically cohesive, aesthetically selective, and resistant of the standard hagiography of a solo show. From the canonical Kitchen Table Series, where the titular signifier of domestic life staged the full scope of politics’ intimacy, to the more curious Slave Coast Series, where the idea of racial ancestry beseeched from its murkiness, Weems consistently probed contemporary social issues in beguiling and lyrical ways. All the more reason, then, to decry the Guggenheim’s curatorial mishandling of the show: several photographic series collided with each other at abrupt perpendicular angels; smaller texts were positioned too closely; and videos were made forgettable when positioned adjacent to the museum’s restrooms. Adding ironic insult to injury, the Guggenheim only presented a portion of the exhibition originally organized by Katie Delmez at the Frist Center for Visual Arts in Nashville. When presenting their first exhibition dedicated to a woman of color, they insisted on sidelining what should have been a major endeavor.

Net and Digital Art

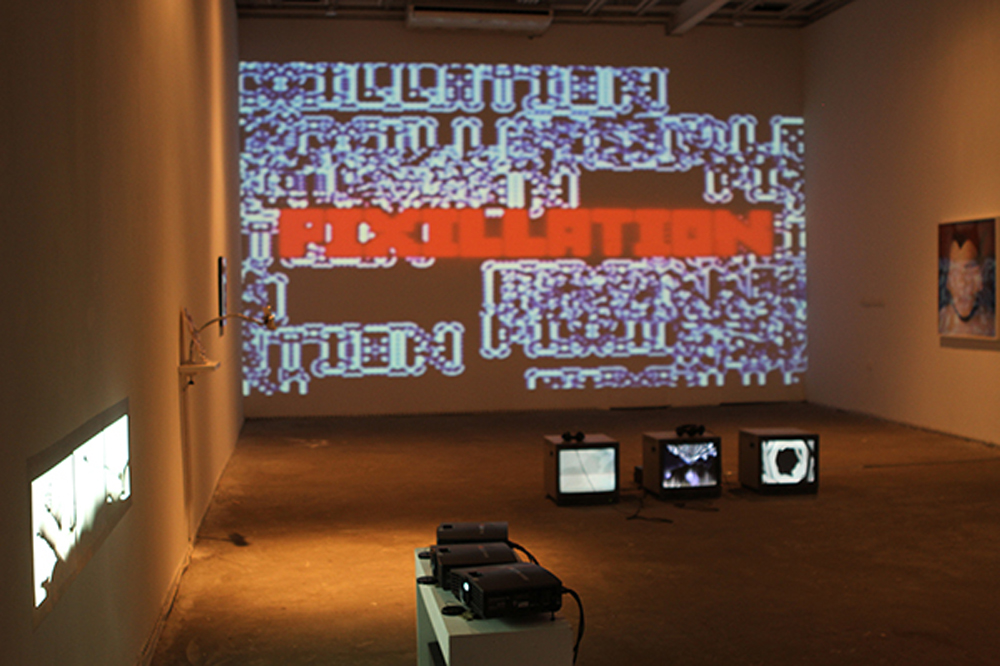

A special nod should go to Coding After Lovelace, an exhibition curated by Faith Holland and Nora O’Murchú, with appearances at New York’s Whitebox Art Center and the Hannah Maclure Centre in the Scottish city of Dundee. Holland and O’Murchú argued for a genealogy of digital and net art created entirely by women, which, when I saw it at Whitebox, took the form of a nicely focused and subtle show. It felt crucial to consider video work by Arleen Schloss, who surely belongs in the pantheon of 1980s female artists like Laurie Anderson or Dara Birnbaum, and who explicitly handled questions around culture and technology. Yet the intelligence of the show resided in understanding a lineage between progenitors like Schloss and contemporary artists taking up a similar mantle, like Jillian Mayer. Lovelace also featured artists included in Lorna Mills’s celebrated film Ways of Something, exhibited at TRANSFER this year. I published my own questions about the piece, but its visibility and success hints at the prominence of net art produced (and organized) by women. It’s hard not to compare this to the more politically-myopic net art which was typically made, this year, by male artists. (See the debacle around Ryder Ripps’s Art Whore project and its clueless defense on social media by what I’ll go ahead and label “net art bros.”)

Montreal’s SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art

SBC Gallery’s 2014 programming prominently brought to mind discussions of institutionalism as they pertained to female practitioners, gender (in general), and identity at large. The space of their small Belgo-Buildng gallery consistently doubled as metonymy for broader political and social spheres. This was done under the direction of the newly-hired Pip Day. SBC pushed the question of institutionalism to the fore with STAGE SET STAGE, Barbara Clausen’s curatorial effort to understand an exhibition as equal parts ephemeral and constant. (The gallery, for example, permanently stenciled a crouched silhouette of performance artist Maria Hupfield into its glass door, while Clausen put together strong film and performance programming from artists like Wu Tsang, Dorit Margreiter, Jacob Wren, Andrea Geyer, and Sharon Hayes.) Following STAGE, cheyanne turions curated the lovely A Problem So Big It Needs Other People, which centered both material works by artists like Daina Ashbee and Susan Hiller and performances around a large table fashioned from picket fences, by Maggie Groat. Gabrielle Moser, and Annie MacDonell’s No Looking After the Internet, which invited participants to handle archival photographs from the Toronto Public Library, was a particular highlight.

Sharon Hayes at SBC and The Showroom

Building on the last entry, my favorite art experience of the year was Sharon Hayes’s presentation at STAGE SET STAGE. Refuting the label “performance” in place of what she calls “respeaking,” Hayes repeated, out loud, the recorded audio from the proceedings of the 1977 American Women’s Conference, listening intently with large headphones and staring straight ahead in a trance, or deep concentration. Focusing on the moment where conference participants introduce a motion concerning sexual preference and discrimination, Hayes didn’t simply “bring alive” history, but conveyed its very means of mediation. The conference could only be understood through Hayes, who delivered the historical script in a manner neither theatrical nor journalistic. The resulting atmosphere was surprisingly tense: one began to ascertain the rhetorical and affective cues of the respective speeches and anticipate the action of an event distant in both time and political radicalism. This wasn’t unlike an older work of hers, the film Gay Power, screened this year at London’s The Showroom alongside the rarely-exhibited Three Lives, a 1971 documentary by the influential second-wave author Kate Millett. Hayes’s film, in which she interviews Millett while they watch footage of the Christopher Street Day Parade, is a rich document of memory, sexuality, and kinship (that’s regrettably only shown in limited release through museums). In Hayes’s work, much like that of Carrie Mae Weems, history does more than render the present as an explanation of why things happen. It implores the present as an agent of desire enmeshed in the opacity of its unknowability. As I write this from a country – the US – that’s actively attempting to account for the violence of its political infrastructure in ways unprecedented in my lifetime, Hayes’s affective methodology feels necessary and urgent.

Female Painters

Despite the perils of making an art-market endorsement, it feels warranted to mention the wealth of painting made by women this year. Michelle Grabner briefly offset an uneven Whitney Biennial with her canny curating of artists like Louise Fishman, Dona Nelson, and Amy Sillman. MoMA’s latest critical The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World, showcases its strongest work at the hands of Laura Owens and Kerstin Brätsch, the latter of whom processes through paint the visual aesthetics of the digital screen, and does so in ways unaccounted for in the exhibition’s vague theoretical rhetoric. Canadians Colleen Heslin and Tiziana La Melia also exhibited intriguing work that contemplates questions of the hand, surface, and construction.

A last-minute addition to this list would be Aline Cautis, who recently delivered a smart, research-based formalism in a new solo show at Chicago’s Regards gallery. Art history’s eagerness to toss away painting in the name of experimental new media and politics may have thrown the co-ed baby out with the bathwater. But new revisions like these examples nuance our account of the determined medium in crucial and exciting ways.

Finally, for a publication committed to signaling “a return art criticism,” I’d be remiss not to mention prime proponents of our craft who take on hegemonic power-brokers. Sarah Nicole Prickett’s spot-on commentary on Art Basel Miami lacerated the event’s Gilded Age-celebration of class, gender, and race privilege. Respected academic Molly Nesbit quietly and intensely revised standard accounts of art theory and history in “The Pragmatism in the History of Art.” And you can accuse me of presenting an academic bias, but Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s lecture at the Institute of Fine Arts on contemporary art history made for some of the most edifying, and frankly, inspiring commentary, this year.

Thank you for mentioning Arleen Schloss in the review about Coded After Lovelace. She’s a forgotten artist, but many people who see her work are blown away by it and realize how talented she is. If you are ever in the neighborhood again, you can come up to her loft, which is across the street from the White Box Art Center.