How much homework should we expect to slog through, en route to art? One could surmise “A lot,” according to Jean Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. From 1963 until Huillet’s passing in 2006, the two produced adaptations of literary classics, intimidating in subject and scope. Now they appear at the Miguel Abreu Gallery, where shrewdly stylish artworks operate like hyperlinks, drawing us quickly into theoretical rumination. With the seraphic entranceway lined by academic texts, the two could not be more at home. A fragmentary study of their work, filled out by evening screenings, Films and Their Sites counterpoints the more typical retrospective of the partners’ films recently presented at MoMA. It appears that Abreu, far from wanting to save the duo from obscurity, has designs on returning them to it.

It’s fitting that the exhibition should meddle with Straub and Huillet’s easy inscription into history, given how their films loosen our purchase on time. In History Lessons (1972), a man in contemporary clothing interviews robed officials of Julius Caesar’s empire about law and commerce. The shots are deftly framed, and the saturated color elicits nostalgic winces. Only rudimentary cuts break the monotonous recitation, spoken in German (with English subtitles). But Abreu is kind to our distracted minds, offering a twenty-six minute excerpt of the film (actually a quality-control clip lent by MoMA to the Venice Biennale’s Italian pavilion, in 2015). Only one work, the brief Mallarmé adaptation Every Revolution is a Throw of the Dice (1977), is shown in its entirety. Through these disembodied bits, Straub and Huillet’s corpus hovers in the memories of its own distribution, degradation, and re-presentation.

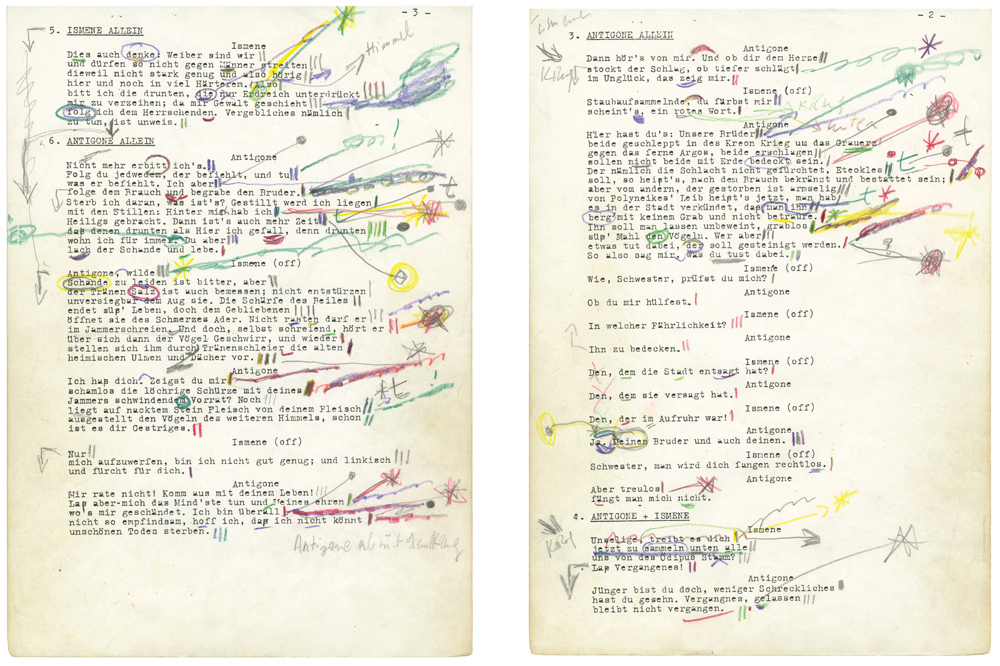

Shot list for “The Antigone of Sophocles after Hölderlin’s Translation Adapted for the Stage by Brecht 1948,” 1991. Text: Sophocles, Antigone, 411 BC, after Friedrich Hölderlin’s translation, 1800-1803, adapted for the stage by Bertolt Brecht, 1948–without Brecht’s prologue.

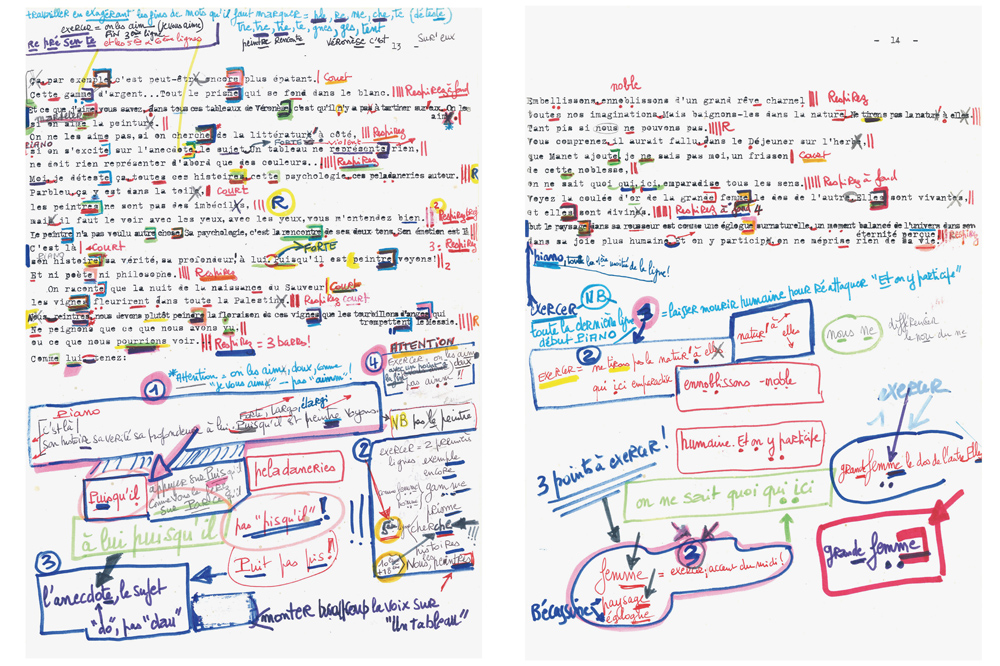

This is a curatorial experiment with uneven results. Some objects, like typewritten scripts lyrically annotated with felt marker, disclose wry pleasure rolling under steely intellectualism. These notes were used to regiment the cadence of dialogue, and are charming in the way of a deadly-serious friend with secretly lavish tastes. In contrast, several after-market photographic stills, mounted on aluminum and hung like montage sequences, call up an auto-generating Eadweard Muybridge effect. The press release instructs us to witness pictorial virtuosity in these stills. Instead, we find a cinematic intensity reduced to hot air.

In several interviews with Cahiers du Cinéma, Straub and Huillet disclosed the obsessive premeditation guiding their work. In total contrast to Hollywood’s patchwork illusions of unified space, their shots were exhaustively planned: the camera placed at central locations from which entire scenes could be observed. The pair seemed to be preternaturally beholden to an idiosyncratic standard of veracity. It’s clear that they felt political consequence guiding these decisions, as their interviews are peppered with allusions to democracy and class struggle. Often, these comments are cryptic and couched in winding technical explanation. So the films are cast both as models for society, and consequential players within it, even as political theories remain difficult to parse.

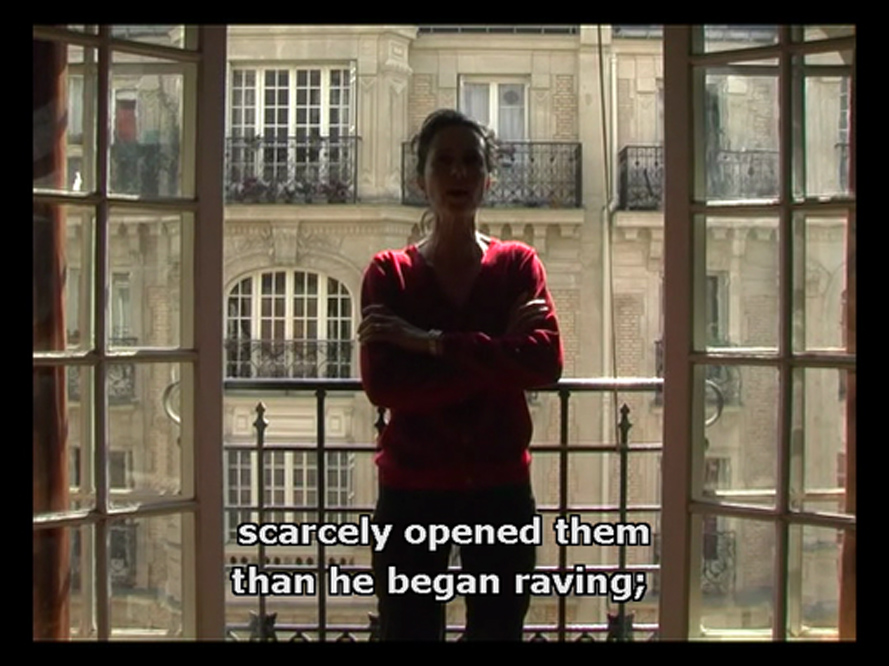

“Corneille – Brecht ou Rome, l’unique objet de mon ressentiment (Corneille – Brecht, or Rome, Unique Object of My Resentment),” 2009 (still).

With a cursory knowledge of mid-century Marxist theory, you can see Straub and Huillet’s terse style dovetailing with those of the dramaturge Bertolt Brecht. In particular, their resistance to cinematic smoke-and-mirrors echoes Brecht’s alienation effect, whereby viewers are persistently woken out of a dreamy fictional space, and reminded of the manipulative ruse enchanting them. But the films are also vastly imaginative, overlapping disparate histories in a way that could be described as fantastical, were it not so prudishly stiff. These contradictions buzz and lurch. And as easy as it may be to cast off the films as pedantic academicism, it would require unique jadedness to dismiss their devotion to a singular vision of politics and aesthetics, obdurately tangled.

This exhibition’s clever achievement is to give Straub and Huillet’s monolithic project an inverted reflection. It allows us a more intimate proximity to the processes that begat the films, and the degradations that have attended them. Returning to the photographs – celluloid-thin placeholders for cinematic rigor comprising a large part of this show – it’s clear that the retrospective presents a disagreement between earnest adaptation and misguided curatorial stewardship.

While Brecht’s storied resistance to the cheap trick of empathic effect is alive in Straub and Huillet’s films, in this show, they become characters in Abreu’s adaptation, and our ability to empathize with them depends on our willingness to undertake an odyssey of reading. It is great reading, mind you, but who has the time? This isn’t a veiled attack on the work’s difficulty. Straub and Huillet’s context – mid-century European politics, Marxist theory, New Wave cinema – is both enriching, and ripe for fresh critical evaluation. One particularly troubling complication stands out immediately: the power dynamic that hovers uncomfortably between more erudite viewers, often characterized by economic privilege, and those who can’t afford the luxury of steeping themselves in literature.

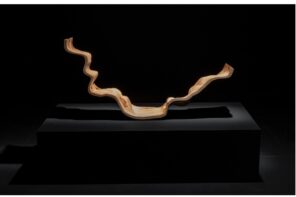

There is a will to break down the normative roles of artist, gallerist, and museum, at work in this exhibition. For their part, Straub and Huillet’s catalogue has been relieved – symbolically, at least – of its duty to history. At the same time, Abreu’s gallery has absolved itself of the responsibility to exhibit fresh and novel work. Academics will happily embrace this unraveling of familiar artworld stratification, citing myriad arguments for the breakdown of authorship and authenticity, from Marcel Duchamp’s “The Creative Act” (1957), to Roland Barthes’s transformative essay, “The Death of the Author” (1967). Knowledge of these histories isn’t required to notice the loving nature of this experiment, though. The exhibition’s fragmented structure is an attempt to let the films live in real time, in a condition prior to their academic reception. But the danger that haunts this gesture lies in an aphorism from the philosopher Alain Badiou, a familiar figure in the Abreu Gallery: “Love without risk is an impossibility, like war without death.” The risk here is of reducing uncompromising and rigorous output to tastefully up-cycled ephemera.

Fortunately, this ephemera is active, and testifies to the pleasure the pair took in text. This is literally the case vis-à-vis the annotated scripts. A similar material richness appears in the celluloid space of History Lessons: edges soften, and blemishes appear, as if seen through cataracts. The fetish value given to degradation, here, is in disagreement with the obsessive attention that Straub paid to the condition of the duo’s negatives, as documented in the Cahiers du Cinéma interviews. So the decision to show the film in this state suggests a murky compromise, and shifting ideals. Either way, the films now testify to the physicality of moving images, a condition today lost in the flow of digitized experience.

The short Mallarmé adaptation Every Revolution is a Throw of the Dice has the dated look of experimental theater, but this only enhances its charm, as the work proposes riddles about perception, bodies, and history. In a small room, the projection is accompanied by a facsimile of Mallarmé’s poem, splayed on a table. The book’s horizontal pages show the constellation typesetting, as important for the author as the poem’s hopscotching narrative. Mallarmé considered the printed page as much a membrane for visual abstraction as narrative immersion. He loosened the components of language from coherent narrative, in a way similar to Abreu’s freeing, in this show, of pieces of Straub and Huillet’s work from their own ouevre. This strategy models the feeling of an arcane language floating in fragments, before we come to understand its peculiar logic. The forces against which this gesture has been deployed are completion and historicization, which deaden artwork as much as preserving it. In some cases, this gambit results in the works becoming vulnerable agents, open to the vicissitudes of immanent experience – alive, in other words. In other cases, crypticness courts tedium.

History might not be a dice game, but it sure seems to play with a dumb chaos. In Every Revolution… actors sit on a Parisian knoll. A plaque tells us that this place is a memorial to members of the Paris Commune who paid for revolution with their lives. The actors recite Mallarmé’s poem, and their stone-stiff postures throw back to the leisure scenes of 19th-century painting. On roulette wheels and city streets, the bouncing and tumbling die produces exhilarating anxiousness. In this work, Straub and Huillet have transformed it into a metaphor for the confused, unpredictable nature of political progress. You’d think we’d feel phantom pains when brought in contact with this violence. On the contrary, Straub and Huillet have created a poetry of remembrance, parched of emotion. The effect is of taught skepticism, beautifully suspended between political conviction and intellectual reserve.

It’s tempting to believe that Abreu has dragged these fragments out of a storage locker in order to make a buck. But that impression fades as the snippets and bric-a-brac mimic the actors in Straub and Huillet’s films, becoming players in an effort to wrest their work from the stale doldrums of art history. When this gambit fails, as with the gassy photographic reproductions, Straub and Huillet’s wrenchingly complex films are reduced to a coterie of vapid ghosts. This is a failure, which can be chalked up to nerdish devotion not understanding its own limitations. But it is also a compromise worth accepting, given the emancipatory effort it represents.