As first impressions go, it wasn’t ideal. On the week he was announced as MOCA Los Angeles’s new director, Klaus Biesenbach managed to alienate the city’s faithful by comparing its art scene to that of Berlin. The comment rankled locals who wanted the director of L.A.’s only public, explicitly contemporary art museum to appreciate their city’s long, distinct legacy of cultural diversity. Then, in his ensuing correction, Biesenbach erroneously championed L.A.’s affordability for artists, which didn’t sit well among a community in which many have been evicted from studios in recent years, as rents leapt to match New York City prices and developers preyed on anyone in precariously zoned live-work spaces. His correction, in fact, sunk easily to the ignorance of his previous sentiment.

Countless op-eds have traced MOCA’s erratic trajectory over the last few years, which has played out like a confusing race in which each runner veers off route. The latest appointment to MOCA’s directorship comes on the heels of the five-year tenure of Philippe Vergne, the French curator who unfurled one male-artist blockbuster show after another (Matthew Barney, Doug Aitkin, Carl Andre). Vergne, who resigned in May shortly after the firing of his chief curator Helen Molesworth, was hired in 2013 to replace Jeffrey Deitch. Deitch was the celebrity-friendly, MBA-holding gallerist who arrived in L.A. in 2010, purportedly to fix MOCA’s financial troubles with his market know-how (he neither did this nor completed his five-year contract). The Biesenbach announcement – “the Biesenbachal,” as it’s been dubbed by skeptics – sounded to plenty of art-invested Angelenos like more of the same: another flashy white man from outside L.A., known for curatorial spectacle, taking the helm of an institution in need of nitty-gritty restructuring. “How DO we shift the tide?” asked artist Micol Hebron on Facebook, her feed among a few forums for dialogue and diatribes about how the appointment related to artworld inequity (chiefly: were any local, female, or of-color candidates considered?). If programming under Biesenbach continues to privilege male artists and spectacle, and the board continues to make decisions that appear more self- than public-serving, how does an art community assert its agency?

In recent years, members of the Los Angeles artworld have tried to do just that, protesting decisions by MOCA directors that seemed insensitive to the lived experiences of vulnerable artists. In 2011, Deitch commissioned Marina Abramović to orchestrate the MOCA gala, and she turned underpaid artist-performers into centerpieces: female nudes laid on moving discs and heads popped up from beneath the white table cloth, rotating as the wealthy ate and drank. Afterward, the non-profit Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions held a heated forum about the performance’s potentially exploitative qualities – which Deitch attended, bravely. In summer 2017, when Vergne brought the Carl Andre show he’d curated at DIA to MOCA, affronted artists tried to foreground Andre’s possible murder of his wife, performance artist Ana Mendieta. They passed out postcards and traced outlines of bodies outside the entrance. But such acts seem a mere blip in the institutional narrative, which continues to alienate as it unfolds.

Protest work by Metabolic Studio outside MOCA’s Carl Andre exhibition. Photo by Sarah Williams / Women’s Center for Creative Work.

Historically, some artist protests have left heavier marks, altering institutional priorities (if only temporarily). In April 1969, artists Faith Ringgold and Tom Lowry, members of the newly formed Art Worker’s Coalition (AWC), called for a “special Black Wing to enable the [Museum of Modern Art] to present a harmonized portrayal of black culture in America.” They gave tours through the museum’s galleries, making their case. When the progressive John B. Hightower became MoMA’s new director in 1970, he listened to the AWC, and to the Guerilla Art Action Group (GAAG), which had demanded that all the Rockefellers resign from MoMA’s board (“This is a group of extremely wealthy people who are using art as a form of self-glorification,” GAAG’s 1969 open letter read). Hightower convened a subcommittee to evaluate the institution’s relationship to “the works of various ethnic groups,” according to a 1970 memo. But it took the board just a year to fire their new director, thanks partly to a staff unionization effort and to the museum’s exhibition of a Hans Haacke work, a ballot box reading “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?”, which drew ire from then-Governor Rockefeller. Haacke’s institutional critique had, by this point, done more to get his curatorial supporters fired than it had to alter the system-at-large (Guggenheim curator Edward Fry lost his job for trying to exhibit Haacke’s exposé on New York slumlords). Recently, after an interviewer pointed out that his work Taking Stock (Unfinished) (1983–84) – which referenced the role Charles Saatchi played in Margaret Thatcher’s election – led to Saatchi resigning from Whitechapel’s board, Haacke pointed out that “Saatchi is still around.” So too is Larry Fink, the MoMA board member who advises President Trump, despite protests at the museum in 2016. Steve Mnuchin did resign from MOCA Los Angeles’s board after becoming Trump’s Secretary of the Treasury, though it’s unlikely that the 372 signatures on an artist-led petition scared him off.

Biesenbach won’t have to contend with Mnuchin, but he will face a board of trustees accustomed to getting their way. “Remake the board,” offered L.A. Times critic Christopher Knight, in an August 1st op-ed that listed recommendations for Biesenbach’s new tenure. There’s certainly a strong case for the suggestion: the board meets at a Beverly Hills hotel rather than the museum, and allegedly pushed for the firing of Helen Molesworth (a brilliant curator who, like many chief curators before her, may also have been an abusive boss). Further, several of its members started their own museums. Former chair Eli Broad has a massive eponymous museum across the street from MOCA while current board chair Maurice Marciano has one in the middle of town, and trustee Nicholas Berggruen plans to open an L.A. institute. The museum needs a director who is administratively agile enough to whisperingly redirect his biggest funders, respecting their influence while still steering them toward MOCA’s greater good. Perhaps Biesenbach will rise to the task, but it will require checking his own ego too.

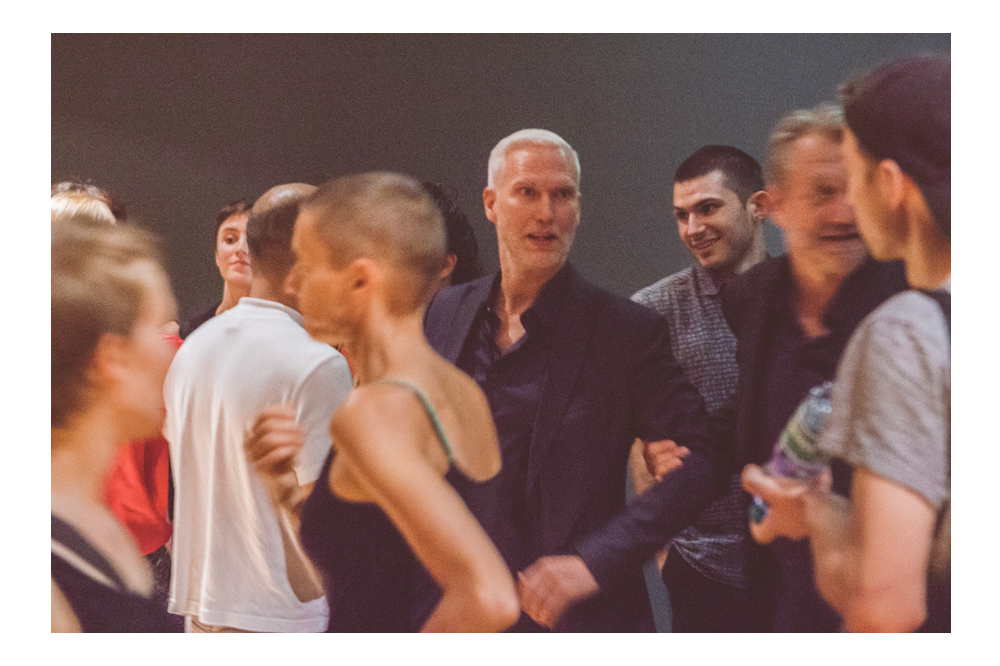

Andrea Scott, in her New Yorker defense of Biesenbach’s appointment, called attention to one of his prominent relationships. “Of course,” she wrote, “Marina Abramović is the artist with whom Biesenbach is the most closely associated, making him Public Enemy No. 1 for fogies who equate the embrace of new forms with endangered traditions.” She missed, somehow, the real reason that the Biesenbach-Abramović alliance irritates many working in contemporary art: both tend to equate their personal feelings with the universal, a habit that doesn’t necessarily encourage a diversity of perspectives. “When I met her, I thought, ‘Oh, God, she’s in love with me’,” said Biesenbach of Abramović in the documentary The Artist is Present. He learned instead that she was “in love with the world” and the attention it could give her.

Biesenbach promised the New York Times he understood the need for diverse programming at MOCA, but he and PS1 coworkers allegedly just rescinded a curator’s job offer after learning she’d given birth. What are our recourses, as a community sick of public institutions maintaining the same-old power dynamics? A new collective, The Artist Acquisition Club of Los Angeles, recently began fundraising among artists to donate to local museums, a way to shape institutional collections from the ground up. But sometimes the answer may be refusing to give or participate at all. Mark Grotjahn turned down the MOCA Gala honor this fall, his market credit and board support making this gesture more impactful than a boycott by artists on the margins (and rather than, say, taking the opportunity to honor a woman or artist of color instead, the beleaguered museum simply canceled the gala altogether). To act against the institution effectively requires an alliance between artists who are continually excluded from shows and mainstream narratives, and those on the inside. “It comes harder to more successful artists than those who are just beginning,” wrote critic Lucy Lippard, a member of the AWC, remembering tensions around the group formed half a century ago: “no artist wants to be told someone else is thinking for him. Nor does anyone like to be reminded he is just a pawn of the system.” If we remind each other, though, for the time being, we can perhaps let go of these limiting notions of scarcity – the myth that only a select few deserve real cultural clout, that success is a finite resource – and accept that diversity makes art more interesting and accessible. Such common cause could fuel the constant effort needed to make dissension felt, through protests, open letters, op-eds, refusals to exhibit, and similar gestures. An artist’s museum, as MOCA’s founders called it, is a terrible thing to waste, especially one with a collection this good.

1 Comment