Invernomuto is an Italian duo who bring an uneasy postcolonial funk to contemporary art, somehow managing to capture the over-the-top brio of, say, dub music while also declaiming fascism. Their art is a mixture of institutional critique (they are invited to make work in the Triennale di Milano archives, for example) and cultural expression, with their latest project, Negus, a triangulated aesthetic that mobilizes music to rewrite history.

As if to confirm my thesis by algorithmic means, an ad from Vimeo that ran while I listened to one of Invernomuto’s dancehall mixes (moody, ambient, clack-y in its rhythms: Wally Badarou) was for Shake the Dust, a documentary on break-dancing around the globe. Invernomuto is all very Vice magazine-ready – indeed, any number of stories have been written about them at Vice Italia – in how they provide an art gloss for record collectors and other aficionados of Jamaican music.

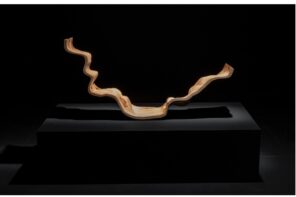

The Negus series of videos and installations – a recent iteration of which played at Vancouver’s Artspeak – are most significant as a celebration of dub and sound-system music. But this strategic choice on the part of the artists is also the work’s greatest stumbling block. A backstory reveals that Italy’s relation to its colonies and fascist history is felt all the way down to local narratives: in this case, a small town, Verasca, where returning colonists burned, in effigy, Ethiopia’s “negus” or King Haile Selassie in 1936. The two artists who make up Invernomuto grew up in the town, and only knew of the event through oral history, down to the term “negus” being a local derogatory term for an idiot or slacker. Determined to reverse historical wrongs they invited Lee “Scratch” Perry, the Jamaican “father of reggae and dub and dancehall,” to stage an exorcism in the town square. In the Artspeak installation, the 2013 film of the exorcism, shot grainy and underlit, plays with a few readymades and a light show. Informed by the group’s work in Ethiopia as well as postcolonial Milan, the installation succeeds by failing to be uptight political art, no footnotes needed.

In some ways, then, Negus encounters the Real of popular racism – the “carnival” of 1930s fascism not far removed from democratic America’s lynchings, occurring at the same time in. As Artspeak director Kim Nguyen puts it in a pamphlet for the exhibition, “the community organized a festive but ultimately disturbing ritual.” This is the conundrum of Invernomuto’s work, how to provide a counter-ritual that “speaks back” to imperialist history. But there is an odd equivalence proposed here: that a tattered and haphazardly recorded (and furtive) performance by Perry will somehow remove the taint (or remind us of the taint?) of another performance, an evil performance. Is art capable of “exorcising” (getting rid of?) evil? Too, how does the mythology of Selassie meet the mythology of the colonizer?

The collective’s use of music is both too unmusical and not enough. The slapdash production values for Negus in the gallery (although the dancehall, etc., tracks that accompany Invernomuto’s installations are more sophisticated) provide the listener with a tinny and granular sound that is in effect a “dub of dub,” taking historical dub (in the 1970s and ‘80s – Badarou’s theme from Countryman) at its own abstraction and further torqueing it. But then another piece sounds like a high-school choir doing a 1930s African-American spiritual. Invernomuto unsettles music taste cultures and expectations: and this is a good thing.

Flipping through my records to find music as I wrote up my notes, I realized that while I had a few King Tubby records, and the usual reggae – Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff compilations – I did not have any Lee “Scratch” Perry. I think it was in part because King Tubby seems less encumbered by the folk mythology of Rastafarianism (which it feels very ‘80s to celebrate) and thus more formal. Which is to say: the formalism of echo and reverb, which dub DJs rely on as they worked from only one turntable. Although I seem to be making the argument here that appreciation of Third-World formalism is better, or less naïve, than appropriation of Third-World politics.

And all of this is to ignore the charge of seeing, in the grimy video, Lee Perry strut his stuff, all red pleather sports coat, spangly Muy-Thai boxer shorts, and a hat covered in sequins. When Perry holds a filthy chunk of ice over his head, muttering “burn down the pope,” you want to sign up for whatever religion he’s peddling.

Equally powerful is the image of Haile Selassie that floats through the film, in a soft-focus treatment that has more to do, as iconography, with such religious commodies as portraits of the Sikh Guru Nanak than that of other Third-World political figures like Gandhi or Che Guevera. More than a political document, then (and having something to do with Renzo Martens’ films, or an unlikely synthesis of Mike-Kelley disorganization and Slav and Tatars’s healthy disrespect for the archive), the biggest thrill of Negus may be its attempt to bring that trashy aesthetic into the art space. Succumb to the music or engage in a social critique: Invernomuto demands that we attempt both, or risk doing nothing.